How R.E.M. transformed from scrappy college band to Hall of Fame rock group

For rock fans of a certain age this may be hard to believe, but it’s been more than 40 years since R.E.M. scored their first Billboard Hot 100 hit with “Radio Free Europe.” The scrappy band from Athens, Georgia, known for its jangling guitar sound and enigmatic lyrics, quickly became a staple of the “college music” scene of the 1980s.

Related Articles

10 notable books of 2024, from Sarah J. Maas to Melania Trump

Hundreds of bookstore staffers receive holiday bonuses from author James Patterson

Nikki Giovanni, poet and literary celebrity, has died at 81

Percival Everett, 2024 National Book Award winner, rereads one book often

Gift books for 2024: What to give, and what to receive, for all kinds of readers

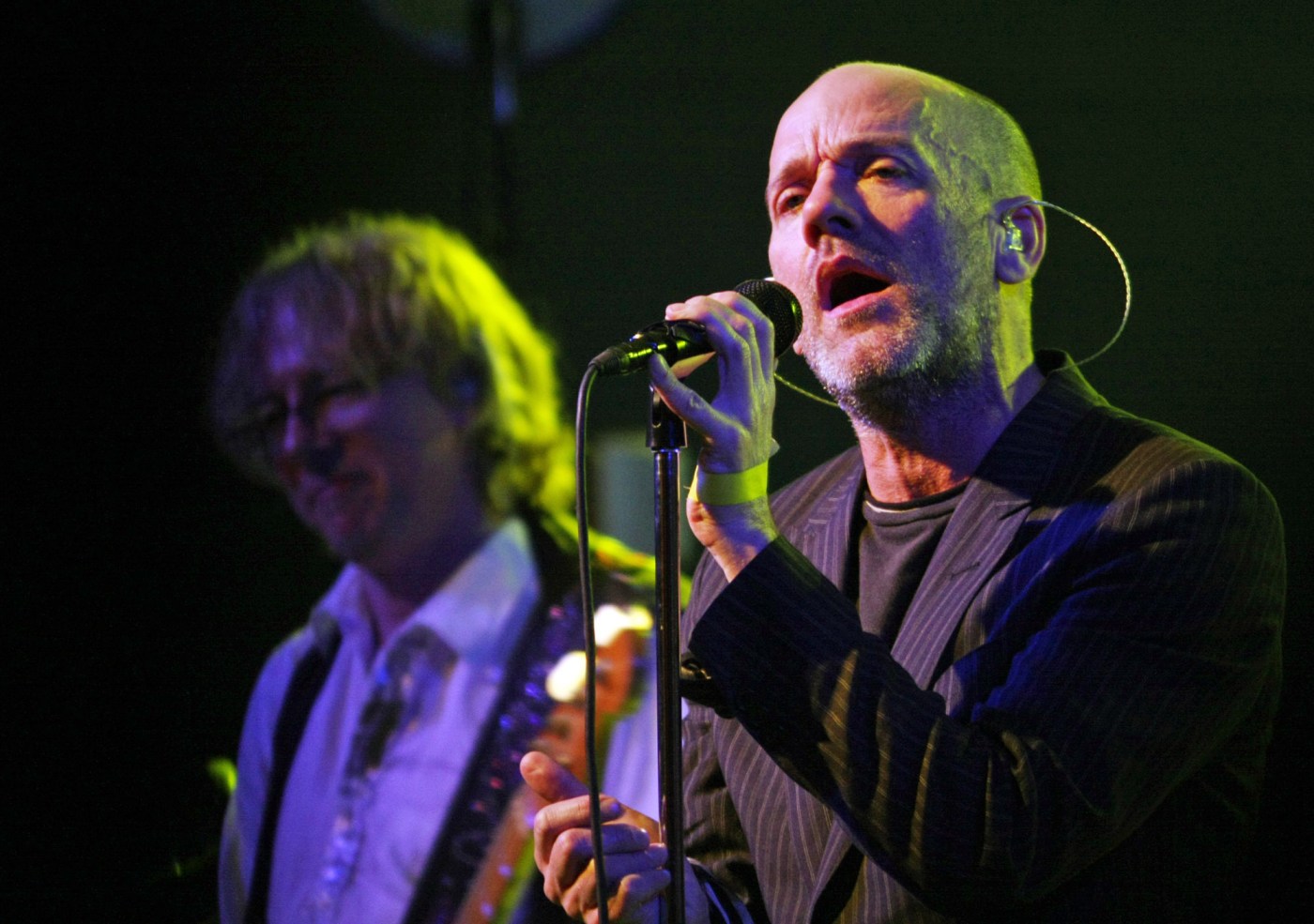

The band — initially composed of singer Michael Stipe, guitarist Peter Buck, drummer Bill Berry and bassist Mike Mills — would go on to have several more hits, including “The One I Love” and “Stand,” before claiming the No. 4 Billboard spot with its 1991 hit “Losing My Religion,” buoyed by an unforgettable mandolin riff by Buck and Tarsem Singh’s haunting music video.

It took author Peter Ames Carlin, the journalist who has written biographies of musicians including Brian Wilson, Paul McCartney, and Paul Simon, a while to jump aboard the R.E.M. train, even though he started college in 1981, right as the band was beginning to turn heads in the alternative music scene.

“None of the kids I hung out with had hipper tastes in me, and my tastes weren’t terribly hip, and certainly not au courant,” Carlin recalls. “But then I would read about them in Rolling Stone, and I would see their videos when they came up rarely on MTV. Then, of course, in 1987, when ‘The One I Love’ broke through and they were on the radio and MTV all the time, I began to get the hang of exactly what R.E.M. was about. From that point onward, I was increasingly on board and then it was impossible not to be a fan.”

Carlin faced a challenge when writing his new book, “The Name of This Band Is R.E.M.” — the band broke up in 2011, and its members are famous for rarely, if ever, granting interviews to journalists. This wasn’t a new problem for Carlin, who faced a similar problem when Paul Simon tried to stonewall the journalist from writing about him. (Simon’s policy, Carlin says, was “A, no; B, [screw] you to the moon; and C, I’m going to kick you there myself.”)

“With Paul Simon, there was this tension, though ultimately that became an animating thing in the book,” Carlin says. “With R.E.M., there was less tension. It was just a sense of, ‘You do what you want to do, and I’m sure it’ll be nice.’”

Carlin answered questions about “The Name of This Band Is R.E.M.” via Zoom from his home in Seattle. This interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity.

Q: You’ve written about a lot of legendary musicians: Brian Wilson, Paul McCartney, Bruce Springsteen, Paul Simon. What made you turn to R.E.M. for this book?

Every time I set out to write one of these books, I run a certain calculus, which is: What’s out there that’s interesting to me, and what [other books] already exist. I started thinking about R.E.M., and they fit all the criteria in the sense that they were this really cool band whose music I really loved, who were super influential — not just in a pop music way, but in a cultural way — and their story was weirdly not told.

There were some books on R.E.M. that came out of England, and they were pretty good, but the one thing that they missed a little bit was that cultural story. They were very focused just on rock and roll and the rock business. I thought, “There’s this whole cool thing that has to do with the South, with alternative cultures and queer culture, and how R.E.M. was so hugely successful, not just in musical and artistic and popularity terms, but also in ultimately expressing this idea about mainstreaming alternative culture in a way that’s still influential today.

Q: You write in the book that R.E.M. was famous for not doing what people wanted them to do. Do you think that was actually part of the key to their success?

Absolutely. In the early ‘80s, there was an [attitude] that rock and roll had become so corporate and conformist. In those early Reagan days, it was just one of those periods where it felt a little like an ebb tide creatively, even though there was always stuff going on in the same way that there’s cool stuff going on now, but if you’re not tuned into the right places, you’re not getting it. This idea of R.E.M. as this band of refuseniks set them in contrast to what was going on at the time.

If that’s what you were looking for, if that’s where your appetite ran, then having discovered them was getting religion because they were talking to you, they speak your language. And if you went to a show and you saw them in a bar in the first half of the ‘80s, the chances were great that if you wanted to hang out and talk to them after the show, they were going to come out and talk.

Q: R.E.M. had a breakout hit in 1991 with “Losing My Religion.” Why do you think this song, with its cryptic lyrics and mandolin, became so popular?

That mandolin riff that Peter [Buck] wrote is indelible. And in pop culture, every so often, people are ready to just zag in the opposite direction of where they’ve been. The song came in the wake of a decade of hair metal and super sleek pop and R&B music. It’s a frustrated love song that ends up in so many ways being about Michael’s identity as a queer person and trying to come to terms with it. When you look at the video and you see all the imagery, you figure out pretty quickly that they’re telling us what forbidden love is, and the outrageousness of it being forbidden in the first place.

Q: Did you think there was any chance the band members would agree to be interviewed for this book, or did you assume they were going to sit this one out?

I had my hopes because I used to live in Portland for a long time, and Peter moved there around 2010. We had a ton of friends in common, and I got to know him, and he’s really cool, and I knew he knew my work and that he liked it. I was really good friends with their manager, and I’ve met the other guys, and I thought that maybe it would work out. They were like, “Go ahead and do it, but we’re done with being rock stars.” Ultimately, they were all very cool about telling friends and family, “You can talk to him. We’re not, but you can.”