Massachusetts high court says families must get shelter before IDing themselves

The state’s emergency assistance shelter system cannot insist that families provide third-party verification of certain information — like proof of their family ties or whether at least one of them is a Massachusetts resident — before immediately placing them into shelter, the Supreme Judicial Court decided on Thursday.

The 16-page decision came out of a class action lawsuit in 2016, when families and civil rights organizations sued the Department of Housing and Community Development, now the Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities (HLC), for denying shelter for certain families who couldn’t immediately provide documentation as a precondition of admittance into emergency shelter.

The emergency assistance (EA) shelter system in Massachusetts is specifically intended to serve families, and HLC has in the past denied groups who could not show birth certificates or other legal documents proving that they were related.6

In every annual budget since 2005, the Legislature has included language that HLC “shall immediately provide shelter for up to 30 days to families who appear to be eligible for shelter based on statements provided by the family and any other information in the possession of the executive office.”

It was the interpretation of this language that is annually rewritten into state law that led the court to their decision.

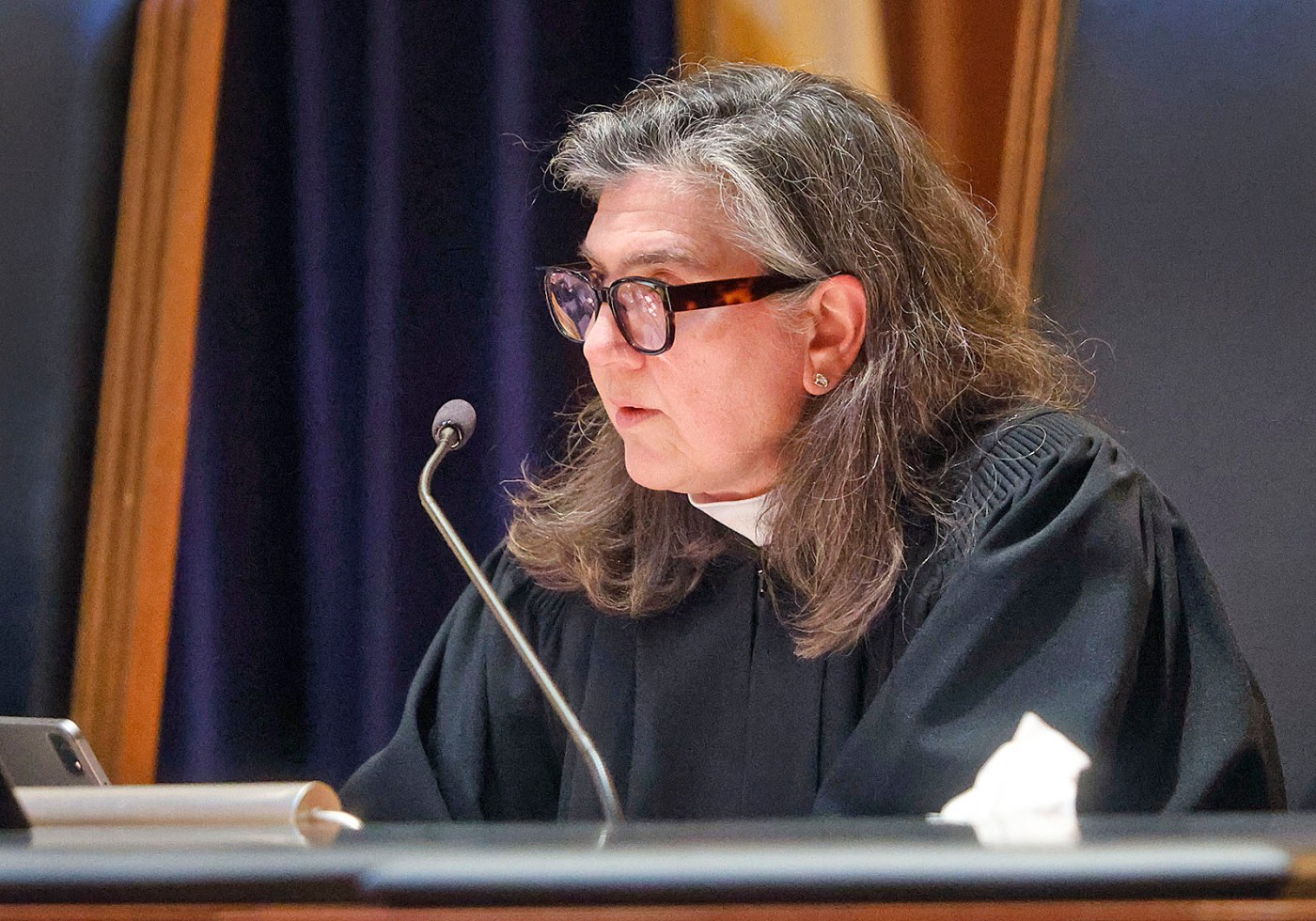

“The plain language of the immediate placement proviso provides that a family must receive immediate temporary placement where it appears that the family meets the eligibility requirements for shelter, and that the appearance of eligibility may be established at the time of initial application by statements from family members and by information already in the agency’s possession. Third-party verification of eligibility criteria is not required at the time of initial application,” says the decision written by Supreme Judicial Court Associate Justice Gabrielle Wolohojian.

Kelly Turley of Massachusetts Coalition for the Homeless, who filed an amicus brief in the case, said the 30 days families have after being immediately placed into shelter often gives them time to either find or recover lost documents, or find other avenues to prove relation and residence.

“In some cases, families are actively fleeing domestic violence, or they experienced a fire, or they have been doubled up and their belongings were lost in the shuffle or somebody stole them, so those key documents that are requested to prove ongoing eligibility may not be ready at the time of application,” Turley said.

She later added, “The legislative intent is to make sure that families who are eligible for shelter are able to access it in a timely way… We think it’s really significant that the SJC has made clear to the administration that families who appear to be eligible should be placed immediately.”

Though Turley celebrated the decision, she said that it is less effective now than it would have been in 2016, when Gov. Charlie Baker’s administration oversaw state agencies, at actually getting families into shelter more quickly.

Since the lawsuit began, the landscape around EA shelters has shifted considerably. Following a surge in demand that started in the late fall of 2022, the Healey administration has implemented a number of strict restrictions on shelter access for the 7,500 families who find temporary housing in the state-run facilities.

Over the past year and a half, in an attempt to control surging costs, Gov. Maura Healey instituted a cap of 7,500 families. Others seeking shelter are put on a waiting list, now called a “contact list.” The governor also instituted a nine-month limit to how long families can stay, as well as a controversial policy that allows families to stay in overflow shelters for up to five days but then disqualifies them from seeking more traditional shelter for six months.

Turley said since most families are going on to the waiting list when they apply for shelter instead of immediately into temporary housing, the SJC decision isn’t likely to have as much of an effect.

“Even though a family is approved presumptively for a full EA placement, they may be waiting days, weeks or months to actually get placed. So in those cases, the 30-day period — they may be out of shelter during that time anyway, because there isn’t a placement available for them,” Turley said.

She and other providers have advocated against the restrictions to EA, and Turley said Thursday that she hopes they will be lifted in the future, and then the SJC decision will have a greater impact protecting families who are fleeing dangerous situations to be able to find a safe place to stay immediately.

Asked to comment on the decision, a spokesperson for HLC said: “We are reviewing the SJC’s decision and the operational impact it may have on the Emergency Assistance program.”

SJC Justice Gabrielle R. Wolohojian (State government photo)