Gaskin: Hub’s rich history of Black women leaders

When many people think of slavery during the Colonial or Antebellum periods, romanticized scenes from the film “Gone with the Wind” often come to mind — vast Southern plantations, elaborate gowns, and enslaved workers laboring in the fields. However, slavery in Northern urban cities such as Boston differed significantly from its Southern counterpart. Boston’s smaller-scale, household-based slavery allowed unique opportunities for resistance, activism, and leadership. As a result, the Antebellum period in Boston saw the rise of numerous influential Black women leaders whose courage, intellect, and resilience profoundly impacted the city and nation. During this Women’s History Month, we owe it to ourselves to learn more about these women.

From the American Revolution through the Antebellum era, Boston’s Black women shaped social justice, abolition, education, religion, and community empowerment. Despite severe societal constraints, they demonstrated extraordinary courage and agency, exemplifying perseverance in the relentless pursuit of equality.

Resistance and advocacy were evident even in Revolutionary times. Margaret Thomas notably served General George Washington by working closely with the Continental Army as a laundress, traveling through critical battles, including Valley Forge, significantly contributing to Revolutionary war efforts. Lucy Pernam, the first Black woman in Massachusetts to seek child custody through divorce, challenged societal conventions and influenced legal precedents. Early community figures such as Rhoda Hall navigated personal hardships while supporting mutual aid societies central to Black Boston.

Boston’s Underground Railroad saw crucial female participation. Women such as Elizabeth Cook Riley, who courageously sheltered fugitive enslaved person Shadrach Minkins, and Harriet Bell Hayden and Isabella Holmes provided vital refuge. Elizabeth Blakeley bravely escaped slavery at age 15 by hiding aboard a ship bound for Boston, becoming a vocal abolitionist upon arrival.

Jane Johnson dramatically escaped slavery in 1855 while in Philadelphia with John Hill Wheeler, becoming an active advocate in Boston’s abolitionist community. Ellen Smith Craft famously escaped by disguising herself as a white gentleman traveling with her husband William, captivating abolitionist circles through their daring story and extensive lectures.

Community organizing emerged through leaders like Jane Clark Putnam, actively promoting abolition and temperance. Sarah Sella Martin, founder of the Fugitive Aid Society, provided tangible support to freedom seekers in Boston.

Black women leaders contributed significantly to intellectual activism and literary expression. Maria W. Stewart became a pioneering writer and speaker, challenging racial and gender inequalities through published writings in Boston’s Liberator newspaper. Frances Ellen Watkins Harper became the first Black woman to publish a short story in America. Harriet Jacobs vividly documented enslaved women’s harsh realities in her autobiography, “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” recognized as a critical slave narrative authored by a woman.

Education was essential for empowerment. Susan Paul integrated abolitionist activism into teaching, actively engaging students in anti-slavery advocacy. Charlotte Forten Grimké, among the earliest Black teachers in integrated schools, used her writings to reflect on race and abolition. Elizabeth N. Smith, Boston’s first Black public-school teacher, also demonstrated vital educational leadership.

Religious activism through figures such as Eliza Ann Gardner challenged institutional gender barriers. Gardner tirelessly advocated women’s rights within the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, shaping religious and community life significantly.

Entrepreneurship and economic independence notably strengthened community resilience. Chloe Spear transitioned from slavery to entrepreneurship, opening a boarding house that hosted community gatherings. Christiana Carteaux Bannister strategically used wealth from her hairdressing salon to fund abolitionist causes.

Legal advocacy and resistance to re-enslavement were exemplified by women like Eliza Small and Polly Ann Bates, who contested re-enslavement in a dramatic 1836 court case. Enslaved women Rose and Cuba challenged the legal system, contributing significantly to Massachusetts’ emancipation trajectory.

Medical breakthroughs involved Rebecca Lee Crumpler, America’s first Black female medical doctor, who published pioneering texts and provided healthcare to marginalized communities. Mary Eliza Mahoney similarly revolutionized medical care as America’s first professionally licensed Black nurse.

In arts and culture, Mary Edmonia Lewis, the first internationally recognized sculptor of Black and Indigenous ancestry, vividly depicted racial oppression and empowerment. Boston soprano Nellie Brown Mitchell captivated audiences, advocating racial equality through performances and invention.

Community philanthropy thrived through Henrietta Sargent Davis, founder of Boston’s Female Anti-Slavery Society, and Lucy Lew Francis Dalton, co-founder of the Boston Mutual Lyceum, significantly strengthening community education and activism.

Writers Harriet E. Wilson, author of America’s first African American novel, and poet Harriet Ware Hall contributed powerfully to Boston’s literary landscape. Abolitionist lecturers Sarah Parker Remond and biographer Nancy Gardner Prince impacted transatlantic abolitionism and women’s rights movements.

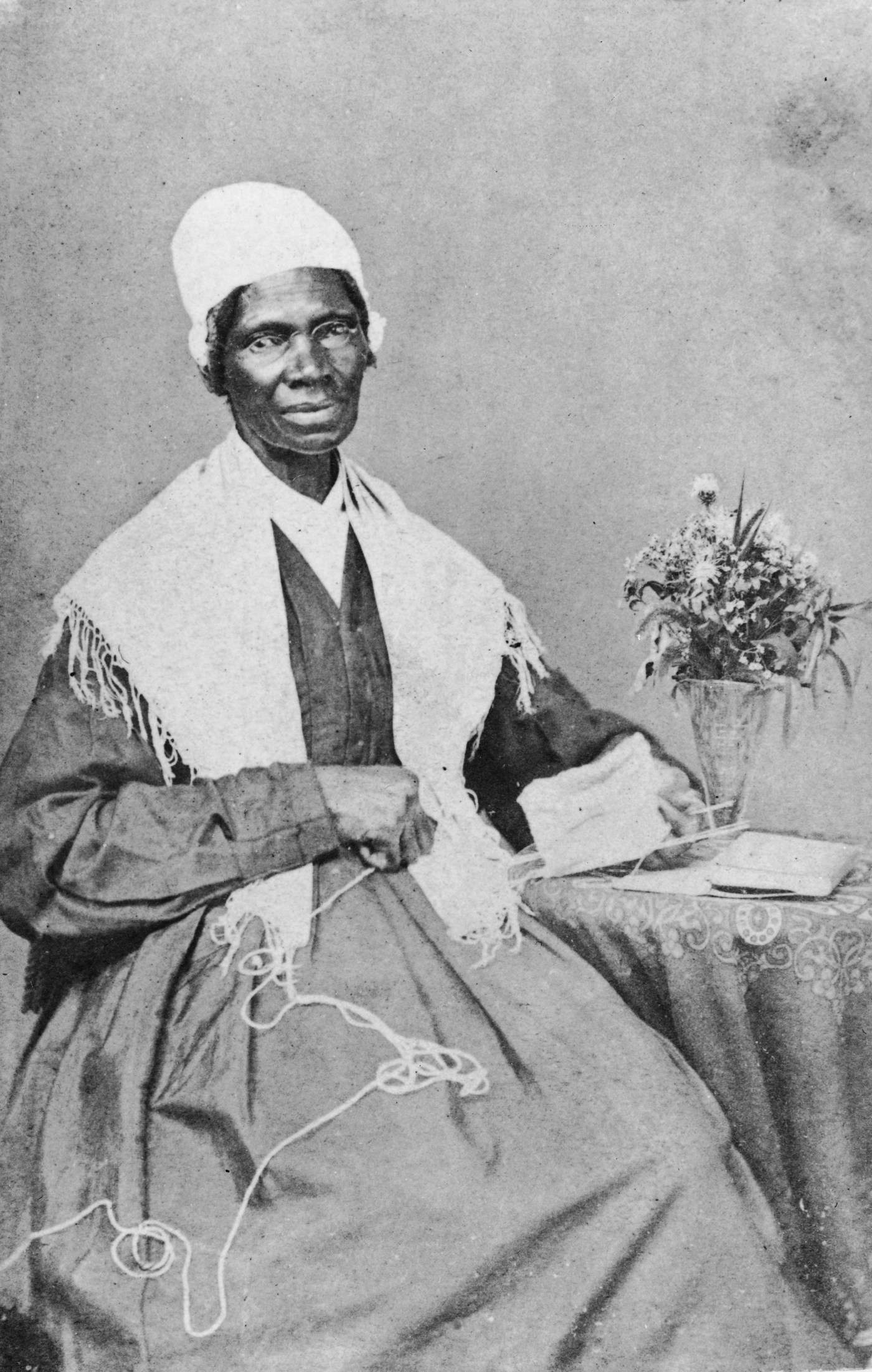

Resistance to discrimination emerged through Prudence Foster, connected socially and spiritually to Boston’s King’s Chapel community, and abolitionist pioneer Sojourner Truth, whose powerful advocacy resonated within Boston’s abolitionist circles, significantly advancing equality movements.

Leaders Amelia Johnson, Henrietta L. Monroe, Virginia Isaacs Trotter, and Rebecca Latimer nurtured social justice advocacy, fostering intergenerational activism. Mary Walker’s legacy continued through the Cambridge Center for Adult Education, demonstrating lasting impacts through education.

Women like Ellen Stewart courageously resisted slavery, bolstering Boston’s abolitionist community, while cultural figures like Nancy Lawson challenged artistic conventions, asserting Black visibility and dignity. Freedom fighters Mary Mildred Botts Williams and Nance Legins-Costley exemplified the struggle and resilience of Black women seeking liberation.

Ultimately, Boston’s Black women profoundly impacted societal views on race, gender, and freedom. Through courageous advocacy, intellectualism, cultural leadership, and resilient community-building, these women significantly reshaped their society, leaving an indelible historical legacy.

Ed Gaskin is Executive Director of Greater Grove Hall Main Streets and founder of Sunday Celebrations