Clark: To keep students in college, focus on mental health

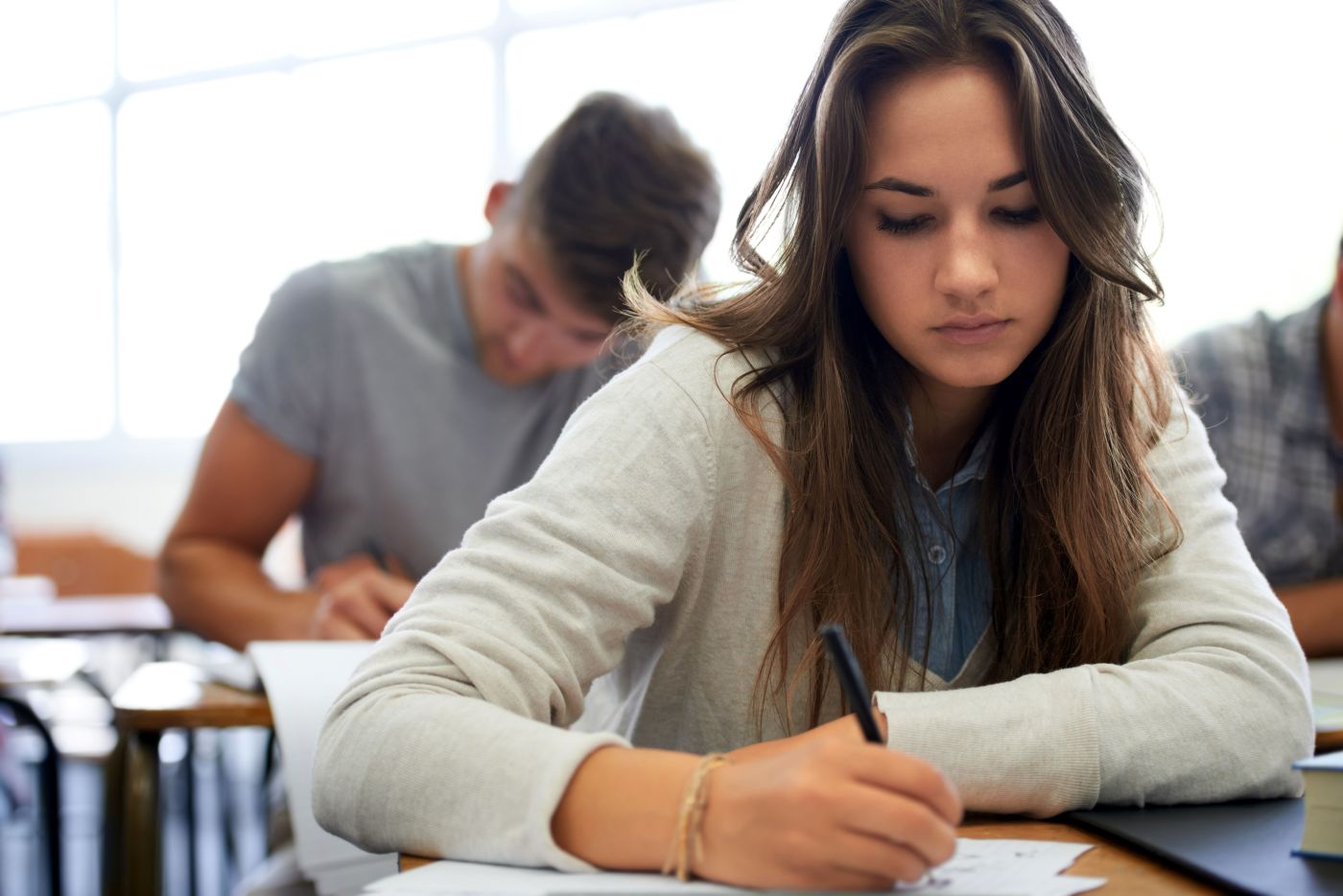

More than one-third of college students report symptoms of moderate to severe anxiety or depression, according to a new survey of over 100,000 students from nearly 200 universities.

Students struggling with their mental health miss out on many of the social and academic experiences college offers. In some cases, mental health issues cause students to abandon college altogether.

Over 20% of students drop out after their freshman year. Just over six in ten complete a degree within six years. Students cite mental health issues and stress as the top reasons they consider leaving school, according to research from Gallup.

Leaving college has many downsides for students, from diminished job opportunities and earning potential to the loss of community and the prospect of debt with no degree. It’s also a problem for colleges, which need consistent enrollment to stay afloat.

Focusing on student well-being can help institutions keep students in school and working toward their degree.

I’ve worked with college students for more than a decade. I’ve seen firsthand that creating a sense of belonging on campus can directly impact a student’s sense of self and improve their mental health. According to the American College Health Association, more than half of undergraduates report feeling lonely. Roughly 30% have shown suicidal thoughts or behavior.

These metrics are scary. They’re warning signs to educators, families, and institutions that something needs to change.

Stressors on students are mounting. Changes to federal student aid programs have left some wondering if they’ll receive the financial support they expected. Social and political unrest — and universities’ responses to it — have induced anxiety among students across the country.

These new stressors are on top of the social and academic pressures students face on a regular basis.

But in too many cases, universities haven’t responded adequately to students’ mental health needs. Campus healthcare facilities are overburdened. A student might be able to secure an introductory appointment with a counselor — and then not get another one for three months.

Some schools put students on involuntary leave if they report a mental health issue. The decision is not easy for schools to make, even when it’s done on the advice of medical professionals. But since it can be hard to return after such an absence, these policies make students less likely to seek help — especially if they’re feeling pressure to continue their education.

A first step for making students feel more welcome is to expand and restructure mental health services. For example, at one campus of the University of South Florida, students who need help don’t just get a 30-minute session with a social worker. They get what the school calls “wrap-around care,” which includes regular therapy, as well as consultations with behavioral, psychiatric, and nutritional specialists.

Schools can also foster a sense of belonging and improve mental health by encouraging mentorships and other trust-based student-faculty relationships. Studies have found that students who believed an educator or staff member cared about their well-being had fewer depressive symptoms and were more likely to thrive.

Professors need more purposeful training on how to extend mentorship to students. Even something as simple as an email signature saying the teacher is available to talk about mental health can help.

Of course, faculty and staff who open their doors to these kinds of conversations are not trained mental health professionals. And often, people of color, women, and members of the LGBTQ+ community are disproportionately sought out by students for this type of emotional support.

At the same time, colleges need to address staff turnover, which ultimately affects students’ ability to foster relationships with mentors. To prevent burnout, administrators should make sure they carve out time for faculty to both support students and pursue professional development opportunities.

Finally, administrators should consider building more places on campus based on the principles of trauma-informed design, which can lower stress. This would help students who have had all kinds of distressing experiences — whether a sports injury, a family member’s illness, or a tough transition to a new culture.

Trauma-informed design includes features like diffuse lighting, sound-absorbing acoustic panels, natural light, and open lines of sight. One example of this approach in action is Princeton University’s new health center, which was designed with student input to include open air, private waiting rooms, and lots of plants. It will open in 2025.

To college administrators, attracting and keeping undergraduates may seem like a question of outspending the competition or building flashier facilities. But campuses that really want to retain students should focus on mental health and belonging. Students need to know that they don’t have to quit school if they’re struggling.

Katie Clark is the higher education market manager at KI, a global furniture manufacturer in Green Bay, Wis. Previously, she spent eight years at Swarthmore College as the assistant dean of Integrated Learning and Leadership and founding director of the Center for Innovation and Leadership. She holds a master’s degree in Higher Education Administration from the University of Pennsylvania and a bachelor’s degree from Smith College in Northampton, Mass., where she is a trustee emerita.