Readers and writers: Enger’s latest novel considers a dark future and a sentient Superior — with hope

Earlier I’d begun to imagine the lake on my side, a protective demigod, the queen herself, adorned with thunder, stepping between me and those who’d have my skin. So much for all that. Deceived in what I felt, and scared, and it seemed very hard that I would find the Slates, locate the precise hidey-hole Lark and I had sheltered in so long ago, only to have it occupied by enemies and have the lake turn every bit as hostile as they were. — from “I Cheerfully Refuse”

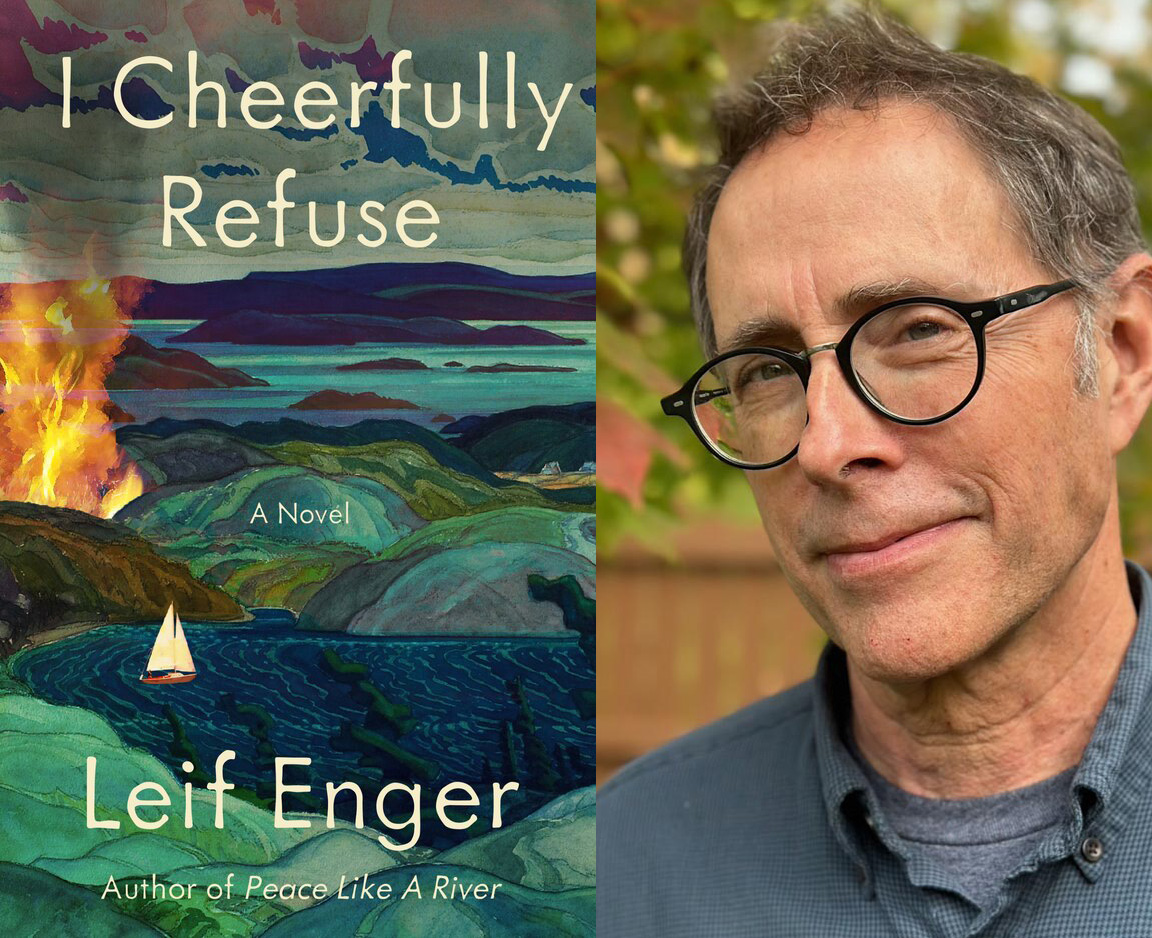

“This is the first time I felt sad to finish a book. I had such a good time writing it,” Leif Enger says of his new novel, “I Cheerfully Refuse,” a hard-to-define story that’s part sea adventure, part thriller, with a little magic along the way. It’s a love letter to bookstores, to reading, and to hope in a dark world, told in the lush prose we expect from the author of “Peace Like a River,” his 2001 debut novel that some readers consider their favorite book.

(Courtesy of the publisher)

Set in the near future in a broken America, the novel’s protagonist is Rainy, a big bear of a guy, a bass guitar player who lives with his wife, Lark, on the shore of Lake Superior, which Enger depicts in the book as a sentient being:

“It’s called a lake because it is not salt, but this corpus is a fearsome sea and if you live in its reach you should know at all times what it’s up to… The lake was dark and flat. It was a blackboard to the end of sight, and any story might be written on its surface.”

Lark owns a shabby bookstore in this time when physical and social infrastructure is crumbling in the United States. Reading has become mostly obsolete because the education system has broken down. There’s a lot of surveillance from government and the ruling class and some people volunteer for work through the ironically named Employers Are Heroes Act for a bit of bread and a place to sleep. Communication is difficult because wars or obsolescence have knocked out GPS. Consumer goods are hard to find and bits and pieces of abandoned motors and all kinds of other items are sold at a makeshift market. Food is scarce. Most creepy is that climate change has warmed the great lake and its long-dead bodies are bobbing to the surface.

At the beginning of the story, sweet and gentle Lark finds what she has been searching for since she was 12 — a rare advance reading copy of of “I Cheerfully Refuse,” a precious book by mid-20th-century cult author Molly Thorn. It is vaguely illicit to have such a thing, so Lark keeps it under the counter.

“Thorn’s book is almost but not quite a memoir,” Enger said in a conversation from his Duluth home. “It provides a touchstone, looking back and forward into the 21st century to say things about past and future. That was a useful idea. Molly is refusing ignorance and despair. I think Rainy understands that cheerful refusal is more effective than any other kind; facing the thing with a smile on your face gives you extra power.”

Fueling the novel’s evil is Werryck, who first appears as a visitor to Lark’s bookstore. A possible shape-shifter, this guy is so scary Enger admits to “a shiver up my spine” as he was writing the character.

Leif Enger (Robin Enger)

“I made Werryck purposely terrifying,” Enger said. “There is something about the whole idea of reading itself being a kind of subversive activity that people in power want to suppress that was fun to write. It’s the joy of risk and elevation just from interacting with literature — high, low and in between — that gives us so much pleasure. When Werryck walks into Lark’s bookstore something dreadful and unholy enters the sanctuary.”

One day Rainy returns home to find Lark’s dead body amidst her ruined shop and realizes someone wants to hurt or kill him. This is when the story becomes a sea adventure as Rainy escapes in his boat and heads across Lake Superior to find an island where he and Lark had a wonderful time, hoping to meet his wife’s spectral spirit. Along the way he is joined by a smart, tough 10-year-old girl named Sol, who’s learned to live in a dangerous society.

The story turns into a thriller as Rainy and Sol are captured (not a spoiler) by Werryck’s men and taken prisoner on a huge ship where medical experiments are done. Rainy is asked to play his bass every night for Werryck the way David played his harp for King Saul in the Old Testament.

“Saul is disturbed in his mind and so is Werryck,” Enger explains. “It’s an interesting dynamic, a man captive summoned to ease the troubled mind of his captor.”

There is ugliness and abuse in these scenes aboard the dark ship.

“The book picks up a sense of urgency and dread here,” Enger says. “That was part of allowing it to be as dark as it wanted to be. I really wanted to imagine the (eventual) hope to have real meaning and currency”.

Darkness and hope

It isn’t surprising that Enger, 63, wrote a book set on Lake Superior. It’s been in his life a long time.

“I think my family fell under the lake’s spell many years ago when we would sail out of Bayfield where we had a 30-foot sailboat for 15 years,” Enger says. “It was old and had a heavy keel (to accommodate) Superior’s winds. It was a lovely way to spend a summer sailing around the Apostle Islands. I knew at some point I was going to have to write about the lake and being on the lake. In my book, Superior feels the way it feels in life: incredibly unforgettable, incredibly alluring.”

It took Enger years to write this novel, which he began in the early days of the pandemic in 2020.

“Remember the world then?” he asks. “It felt claustrophobic. I wanted to write something kind of nautical. I’ve always been fond of nautical adventure — Robert Louis Stevenson, ‘Moby Dick.’ I needed a story that would allow a bit of dystopia, a very dark world but one that would pull me through to hope on the other side. Rainy’s voice was very accessible. Early in the dark, in my office, Rainy was waiting to reveal his story.”

Although “I Cheerfully Refuse” has been described as speculative fiction or magical realism, Enger doesn’t think the book is a total departure from his previous books. For instance, there’s a bit of mystery in “Virgil Wander,” when a man is seen standing on or in the water, his back turned, doing nothing. And there may or not be miracles in “Peace Like a River.”

“There is a through line from my first book to this one,” Enger says. “I suppose it’s a departure in that it takes place in the future and I haven’t attempted that before. You don’t want to repeat yourself.”

Enger says what runs through all his books is his narrators’ shared characteristics.

“They tend to be kind of wide-eyed, pretty open-hearted and hopeful,” he explains. “The world in the pandemic of 2020 did not look at all hopeful. There was a lot of upset in the cities, protests about (the murder of) George Floyd and the clueless response from people in power. I needed to write an imagined world where the old rules didn’t apply, but with ways to exist and be joyful.”

Some readers have criticized Enger for not explaining enough about the novel’s dystopian world.

“I chose to set the story in a particular moment in time, a few decades in the future,” he says. “I didn’t worry about explaining. So many books get written that do a beautiful job of that. I just wanted to tell one guy’s story. He doesn’t know any other world. It’s a time in which everything is owned by a few, servitude is common, churches are run by warlords. That is the future that seemed the most likely if you read the news.”

It started with a baseball player

Enger grew up in Osakis, near Alexandria. In the late 1980s, he and his older brother Lin collaborated on writing a series of crime novels featuring a former major league baseball player. Published under the pen name L.L. Enger, the series did well enough but took too much of the authors’ time. But both agreed the experience helped them become better writers. Lin went on to teach English at Minnesota State University Moorhead. His debut novel, “Undiscovered Country,” was published in 2008, the same year as Leif’s “So Brave, Young, and Handsome.”

Leif was a reporter for Minnesota Public Radio for 16 years before writing “Peace Like a River,” which was so successful he was able to quit his job and write full time.

When that widely praised novel was published, Leif and his wife, Robin, were living in an old farmhouse on a 56-acre spread in Aitkin County where they raised their sons John and Reed, known by his middle name Ty. John followed in his father’s footsteps, working at MPR and publishing his debut novel, “Radium,” in 2022.

The family lived on the farm for 21 years, but after the boys married and left, Leif and Robin looked for a change.

“We began to feel isolated,” Enger recalled. “We lived 90 miles from Duluth and drove there often. We bought an old house with more space than the previous one with an attic where Robin can spread out her quilting.” The house is six or seven blocks from Lake Superior, which they can glimpse from their top floor when the trees are bare.

When the conversation returned to “I Cheerfully Refuse,” Enger muses that authors can help offset current feelings of national despair: “Just the act of writing. That’s an act of hope.”

If you go

Enger’s Twin Cities metro-area events for “I Cheerfully Refuse” (Grove Press, $28):

6 p.m. Wednesday, April 3, Barnes & Noble, 3230 Galleria, Edina

6 p.m. Wednesday, April 24, Next Chapter Booksellers, 38 S. Selling Ave., St. Paul

7 p.m. Thursday, April 25, Excelsior Bay Boks, Excelsior

2 p.m. Sunday, May 5, Lowell Inn, 102 Second St. N., Stillwater, in conversation with Minnesota writer Benjamin Percy

Related Articles

Literary calendar for week of March 24: Our Mary Ann Grossmann talks to author Danny Klecko

Book artist wins award for ‘Letters to Amerika’

Stillwater: ‘House of Broken Angels’ by Luis Alberto Urrea is this year’s ‘Valley Reads’ pick

Sarah Tomlinson blends rock music, celebrity and ghostwriting in debut novel

It’s ‘Read Brave St. Paul’ week