At ‘Climate Cafés,’ mental health experts and environmentalists create a community to tackle climate anxiety

CHICAGO — Ten years ago, Beth Beyer’s youngest child walked out to Lake Michigan on a mild winter day and cried.

The Lincoln Park resident thought her son would be excited about spending time outdoors, but the seventh grader was distraught thinking about what the unseasonably warm weather meant for the world and its climate.

“I was like, ‘Wow, you’re taking this in a way that I had no idea,’” Beyer remembers saying.

Since, Beyer’s advocacy and nonprofit work has allowed her to keep her “ear to the ground” and share what she learns from other environmentalists with her two sons to ease their eco-conscious minds. She is the executive director of The Technology Alliance, which makes new technologies available to local underserved communities, and also works with the Chicago Wilderness Alliance.

“We need to figure out how we channel this anxiety,” she said. “How do we create hope?”

Beyer recounted this during a Climate Café, one of a few gatherings that Chicago psychotherapist and clinical social worker Libby Bachhuber has helped organize for those struggling with the emotional burdens of climate change: from anxiety to grief, from guilt to shame.

Many mental health professionals agree the most effective way to deal with the difficult feelings brought up by the enormity of the climate crisis might just be to slow down, pay attention to those feelings — as uncomfortable as they may be — and talk through them with other people.

“Unless we can process our internal responses to climate change, we are not going to be able to respond appropriately to it,” Bachhuber said.

After joining the regional team for the Climate Psychology Alliance North America, Bachhuber trained last year on how to hold small group sessions. She is planning three cafes in the next three months.

She organized the recent Climate Café at the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum alongside Haven Denson, coordinator for the museum’s Chicago Conservation Corps program, which trains community leaders in grassroots organizing and climate action. Denson said many young people like her Gen Z peers are mentally checked out when it comes to climate issues.

“Everybody that I talk to is mostly ready to give up. All we hear is doom and gloom,” Denson said. “We may as well just give up, it’s already too late.”

And the numbers back this up. A study published in the medical journal The Lancet in 2021 found that almost half of Americans surveyed between the ages of 16 and 25 were very worried or extremely worried about climate change and thought humanity was doomed because of it.

“That is why I think this is so important, having these spaces where we can not only talk about solutions, but also just talk about (how) we are in this together, we’re not isolated, it’s OK to feel this way,” Denson said. “To acknowledge these feelings and emotions, to actually process them so that we can then move on and find those solutions.”

Ecological anxiety and grief

Some may dismiss eco-anxiety, or fear of environmental catastrophe associated with climate change, as one more term in a long list of “therapy speak” — buzzwords related to psychotherapy and mental health that are often used excessively and incorrectly.

But just in the last decade, the number of Americans “alarmed” by climate change has doubled to more than one-third of the population, according to the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication.

“People tend to come in and they are worrying a lot,” said Marilee Feldman, founder and clinical director of the Life Counseling Institute in Willowbrook and Park Ridge. She is also the Illinois regional coordinator for the Climate Psychology Alliance North America, which trains psychotherapists to address climate issues and concerns.

Feldman said clients often ask themselves: “Where should I live? What is the future? What will it be like for my children?”

Another feeling particular to the climate crisis is ecological grief; a great sadness about the loss of nature and species, about a lack of safety and about unfulfilled potential. These and other overwhelming feelings can be exacerbated by a sense of isolation, according to Feldman. “So, that just adds fuel to the fire,” she said.

A growing number of climate-aware psychotherapists are hoping to help their patients move past denial and into climate resilience. By accepting reality, people can sort through complex feelings and grow able to tolerate them. Anxiety, grief and despair, anger and rage can all be transformed — by talking with other activists, joining a support group, meeting a climate-aware therapist — into productive action.

“I think there’s hope here, in terms of really becoming more adaptive, dealing with all those thoughts, feelings, body sensations,” Feldman said, “to where you take that anxiety, you take that grief and all of that upset, these emotions that are very powerful, and you channel (them) into … your love for this world and making things better and figuring out what’s important to you.”

Guilt and shame

According to The Lancet study, about 42% of young people surveyed in the United States felt guilt and over 44% felt shame in relation to climate change. An associate professor of environmental ethics in the Divinity School at the University of Chicago, Sarah Fredericks said deep shame can cause people to hide or retreat and become paralyzed, unable to act.

Guilt and shame in the context of climate change first piqued the ethicist’s curiosity when she lived in Texas a decade or so ago. She owned an old home that she wanted to renovate in an ecologically conscious manner, so she began perusing blogs and websites about eco-friendly design.

But Fredericks also found many people online who were plagued by guilt, in response to doing something wrong, and shame, or having negative feelings about one’s whole self. For instance, someone felt bad about driving a minivan around town, someone else was embarrassed to admit they used air conditioning regularly, and yet another person would always forget to bring reusable bags to the grocery store.

“It was interesting to me, because people kept using this language that I would think of as very religiously coded language,” Fredericks said. “They would say things like ‘I’m an eco-sinner,’ or ‘I’m a bad person.’ They were judging themselves. And I thought, as a religious studies scholar: Is that what’s going on here? Are these people affiliated with particular religious traditions? Are they not? Where’s this language coming from?”

At the time, however, there was basically no existing academic literature documenting this phenomenon; her peers and colleagues told Fredericks it made no sense for people to feel that way as individuals since climate change is a systemic problem.

But the more she read and studied discussion boards, websites and books to learn what people were doing about these feelings, Fredericks realized there seemed to be something affirming and validating when people helped others put their guilt and shame into perspective; mistakes were recognized as such and not as an indictment on a person’s morality.

“As individuals we exist in communities, and wouldn’t be able to exist without our communities,” Fredericks said. “But a lot of the environmental guilt and shame relate to our community. … There are structures in our community — financial, infrastructural, physical, social — that shape who we are. So we need community responses. And we need community support, the kind of cheerleading or moral support that friends and community and families can offer us.”

Sitting with differences

Participants at the recent Climate Café at the nature museum were asked to bring a natural object that illustrates their connection to climate issues.

Carolyn Vazquez brought her 10-year-old daughter, Bella.

“Well, she’s natural!” she remembers saying with a chuckle. “She’s my object because she’s the future. … What am I leaving her?”

For Vazquez, looking out for the environment is a personal and professional endeavor. The Auburn Gresham resident is a community activist and the CEO of hemp manufacturing company Think ReHemption which advocates for sustainable, organic and climate-smart agricultural practices.

After the conclusion of their Climate Café and still sitting in a circle, Vazquez and Beyer organically and almost inevitably waded into a conversation about race. Both women, similar in age but with distinct backgrounds, share a passion for the environment and hope to get their communities involved in these issues.

Vazquez pointed out that most of her neighbors in Auburn Gresham have basic needs like access to food and concerns like gun violence, matters so urgent they can divert attention from environmental problems.

“There are young, African American youth and parents, families who are concerned about it, but you don’t see them,” Vazquez said. “You don’t hear about them. Nor do they feel empowered enough to get a bunch of people who really don’t want to hear that language, who are worried about different stuff.”

And because suburban and North Side communities don’t see as much violence, she said, their residents might have more time, energy and resources to direct toward climate advocacy. “The playing ground will never be equal,” Vazquez added.

Beth Beyer on the lakefront near Diversey Harbor in Chicago, on Dec. 22, 2023. (Trent Sprague/Chicago Tribune/TNS)

But Beyer herself feels challenged by the fact many people in her Lincoln Park neighborhood don’t feel connected to one another. “Some of us don’t even know what’s going on,” she said. “There’s no forum for it.”

“I think these are tough conversations sometimes, and people come from different places. So (with) this small group,” she gestured to the Climate Café participants and facilitators, “I think we’re going real far. … It just helps to get insight.”

Bachhuber sat to the side, quietly listening. She finally spoke after a lull in conversation.

“It’s challenging, all over in different spaces but including in environmental spaces, to sit with the reality of these differences, how deep they run, and how psychologically they affect us,” she said. “There’s a universality to (climate change), but there’s also a specificity to it, of how different communities are affected. (This conversation) is kind of cool because to me, this is some of the work that needs to happen. … I don’t think this solves with us just being separate and not figuring out how to sit with the discomfort of differences.”

Rebecca Weston, co-president of the Climate Psychology Alliance North America, noted that some people may think or suggest climate anxiety is an experience limited to white, middle-class people who are concerned about losing summer homes or getting insurance on their coastal properties. But that’s not true, she argued.

“The people who are most worried about climate change are people of color, predominantly women of color,” she said. “The people who are most active around these issues are people of color. The people who are most advocating for policy change are people of color. So to suggest that climate anxiety is just a feeling of the wealthy elite is not correct.”

As an activist, Vazquez said she often finds herself “mentally tired and drained” from trying and failing to get people in her neighborhood, which has historically suffered from disinvestment, to pay attention to environmental issues.

“I feel like these moments help you connect in a safe space where you feel like you can really talk to people,” she said.

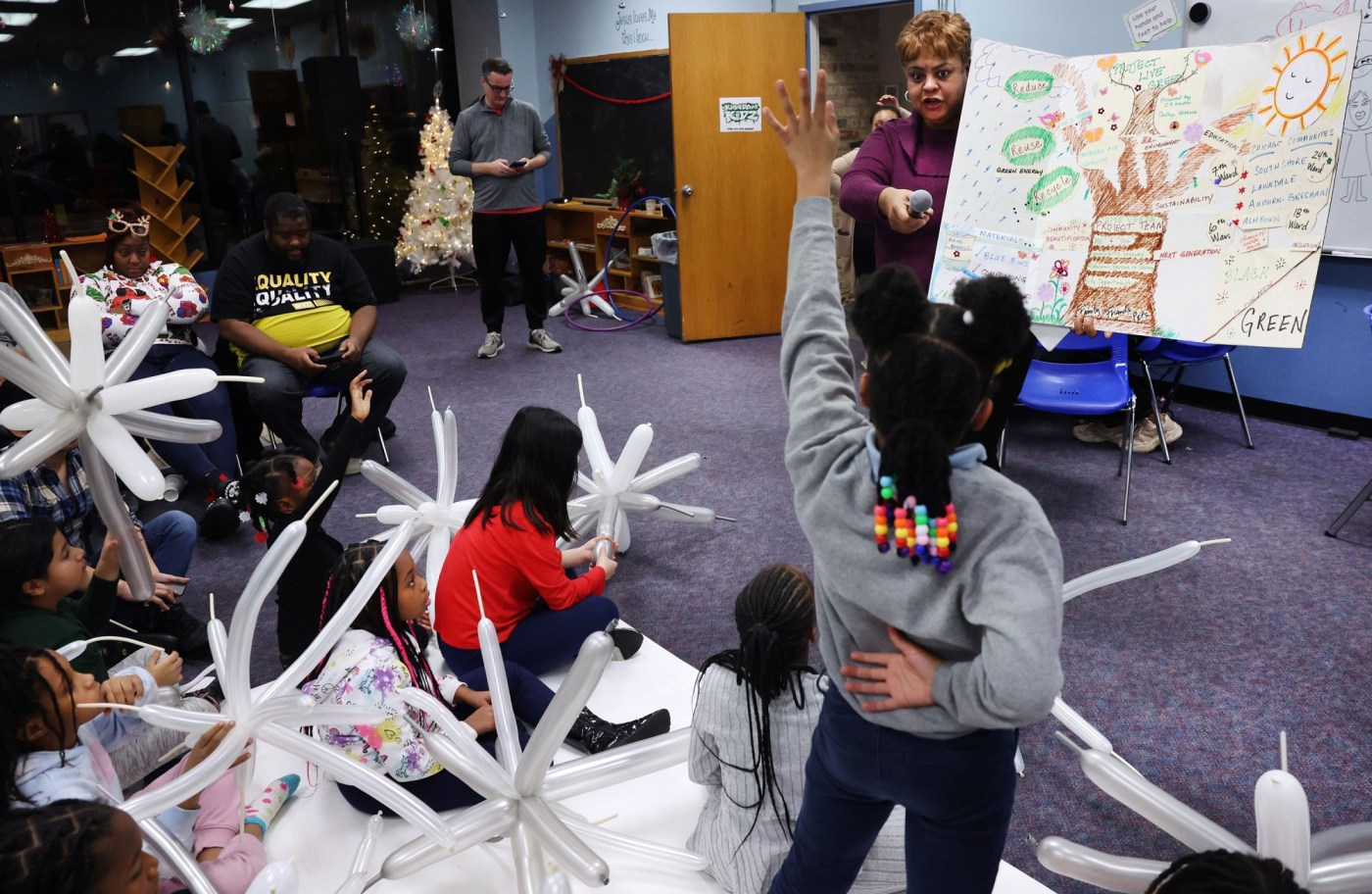

A poster board used by Auburn Gresham neighborhood resident Carolyn Vazquez at an event on Dec. 22, 2023, for kids about things they can do to help fight climate change. (Chris Sweda/Chicago Tribune/TNS)

From individualism to community

When Ren Dean, the owner of Skunk Cabbage Books, was drawing up a business plan for the Avondale bookstore, one of their main goals was to create a place where folks could talk about their collective futures in the context of climate change. So Dean began a book club for nature-focused writing.

“I personally was really feeling like I needed a space, a physical space, to talk to other people and figure out how to find each other and how to support each other,” Dean told the Tribune. “How do we engage with this in a way that isn’t so paralyzing, that feels like there’s something we can do and (there’s) ways we can support each other?”

Dean said the group had been reading a lot of good writing about grappling with the immensity of climate anxiety and how community could offer a starting place to begin processing these difficult feelings. But they were also itching to find a space to talk about their mental and emotional experiences instead of just reading about them.

“There’s reading that and recognizing that that’s the answer,” Dean said, “and then there’s the next step of: How do I do that? It felt really big and hard for me, personally.”

Which is why Dean jumped at an opportunity a few months ago, when Bachhuber reached out with the idea of holding a Climate Café at the bookstore. “It was a really kind of perfect thing for us to host,” Dean said.

“We have a very individualistic culture that puts people in a really difficult position as they start to process climate change and learn about it in isolation,” Bachhuber explained. “And our culture of individualism is part of the problem, it’s part of what got us into this situation in the first place.”

Talking through their shared feelings and emotions on climate change can help folks untangle themselves from individualistic approaches to the climate crisis, which can oftentimes feel futile and discouraging.

“We were raised that way,” Vazquez said. “How do we say, ‘Hey, there’s enough pie for all of us,’ to solve this problem?”

___

©2024 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.