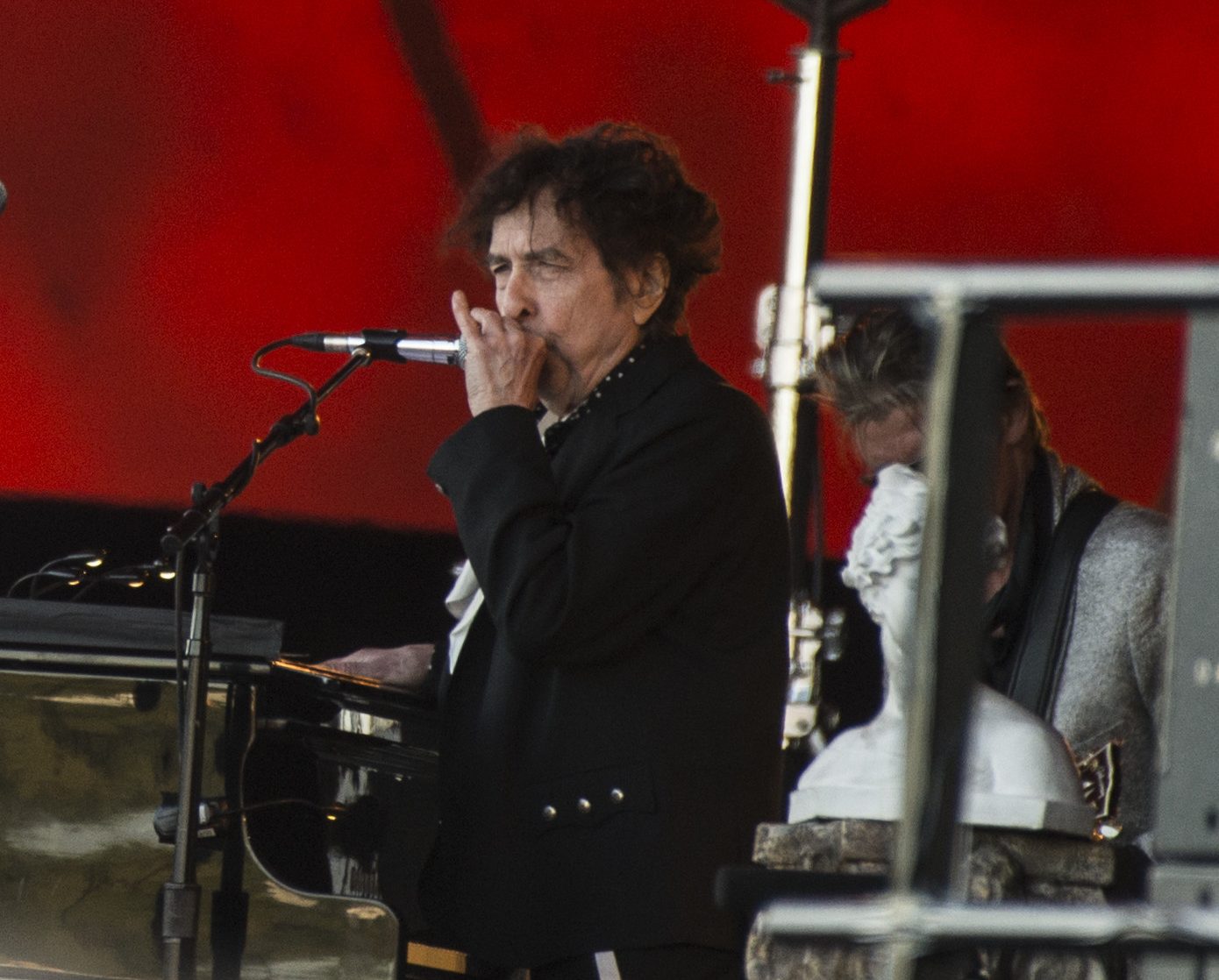

Bob Dylan shows ’em how it’s done

Bob Dylan is 82.

That’s a scandalous age.

In an era when Mick Jagger is 80, looks 70, moves like he’s 45, and acts like he’s 25, being 82 is a pop music sin. Youth rules (Billie! Olivia! Lil Yachty and Lil Pump!) as it did when Dylan plugged in at Newport in 1965. And when youth can’t be factual, it must be perceived (see Jagger, Tom Cruise, Carly Rae Jepsen, the cast of every show about teens).

But Bob Dylan doesn’t want to be young, act young or look young. On Friday at the Orpheum Theater — the first of a three night stand at the venue — Dylan began by singing, “This ol’ river keeps on rollin’, though/No matter what gets in the way and which way the wind does blow/And as long as it does I’ll just sit here and watch the river flow.”

Bar band frontman and Greek chorus, Dylan spent the night like he’s spent most of the past 35 years, on tour, acting as an impish, earnest, introspective tour guide of mortality.

Mining recent album “Rough and Rowdy Ways,” Dylan stuffed his set with new songs about life and death, and about beat poets, black riders, and bluesmen who died half a century ago, resurrected monsters, Anne Frank, Indiana Jones, and a lifetime spent crossing Rubicons. Then he placed those meditations next to finely curated, completely reinvented classics from his catalog.

Now a focus on mortality doesn’t mean a focus on the dark, glum or meek. He sings about how he and we spend our time, and those reflections often come via barn-burning rock ‘n’ roll.

Adolescent, boastful, and deliciously cruel, not far from Bo Diddley’s “Who Do You Love?” or Miley Cyrus’ “Can’t Be Tamed,” new song “False Prophets” was a rager. He simmered the song a while only to turn up the heat at the end and let it boil over, the guitars powering through a big hook, Dylan pounding at the keys of his grand piano.

Dylan as a barn-burning piano player might seem far-fetched for anyone who hasn’t checked in on him since the Rolling Thunder Review, but he’s excellent behind the keys, hinting at decades spent listening to stride, swing and boogie woogie. These skills and a crack five-piece band behind him had Dylan sending songs new and old back in time. (Maybe he does care about aging, aging backwards, stylistically he’ll reach New Orleans a century ago by age 90.)

He gave space on an uproarious “Gotta Serve Somebody” for the guitarists to wail rockabilly style. “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” built to a knotty jam somewhere between the Allman Brothers and jump blues king Louis Jordan.

When not honky tonking, he got slow, leading his band slogging through molasses. Fresh tunes “Crossing the Rubicon” and “I Contain Multitudes” inched along with tense energy.

Or he got tender. He did a reverent, intimate reading of the Dead’s “Brokedown Palace.” He turned “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You” into a love letter to his fans, an acknowledgment of lifetimes spent communing with the artist and audience. He gently considered his constant inspirations — old world poets, classic folk balladeers, traveling bards — on “Mother of Muses.”

In an era where so many songwriters struggle with or have given up on meditation of mortality, Dylan remains. In an industry that doesn’t know what to do with artists who aren’t 25 or can’t play at being 25 for stadium crowds, Dylan remains. This ol’ river keeps on rollin’.