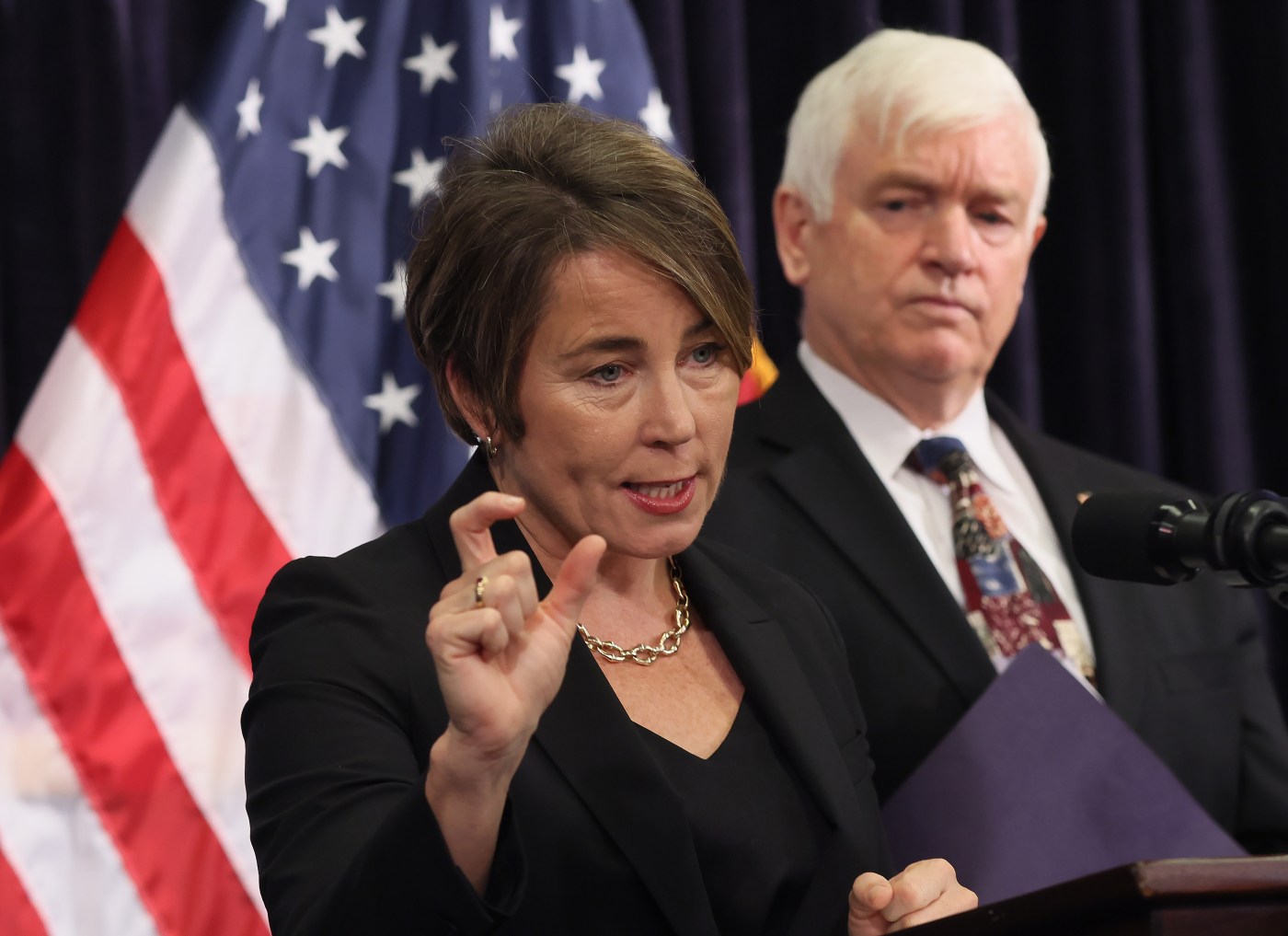

Massachusetts ‘open to time limits’ for families staying in emergency shelters, Healey says

State officials are “open to time limits” for the thousands of homeless families living in emergency shelters, Gov. Maura Healey said Thursday, a potential move that drew mixed reactions from shelter providers and resettlement agencies working on the ground.

Days after her administration released rules that grant the power to curtail shelter stays, and only a day after a judge cleared the way for the state to cap the system at 7,500 families, Healey raised the possibility of cutting short families’ time in one of the hundreds of sites across Massachusetts, including a sweeping net of hotels and motels.

“We’re open to time limits, whatever the moment requires,” Healey said at an unrelated event inside the State House. “We’ve been talking as a team, and we’ll have more information about that. Again … I don’t want to see people out on the street. I understand people’s vulnerability.”

Healey has repeatedly said the emergency shelter system — strained this year by a surge of newly arrived migrants coupled with crushing housing costs — is on the brink as funding runs out and the budget faces a deficit without a cash infusion.

But for providers and resettlement agencies on the frontlines of the shelter crisis, there is division over the idea of time limits as the state inched even closer to capacity, with the Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities reporting 7,404 families in the shelter system.

The International Institute of New England is working with 225 families that are staying in hotels and motels. With more state funding, the agency could move a “significant number” into permanent solutions, freeing up space for other families, the organization’s CEO, Jeff Thielman, said.

Resettling families takes time, often six to eight months, and the International Institute of New England is “very wary of a timeline because it doesn’t reflect reality,” Thielman said.

“You cannot put a timeline on people in shelters unless you have a system to get them out. And that system needs to be funded. And so far I have not seen it. I have not seen a plan to get people out of the shelters,” Thielman told the Herald. “I have not seen a plan to fund organizations like ours that are experts on resettling people.”

Since declaring a state of emergency in August, Healey has said work authorizations and employment are key to moving migrant families out of temporary shelters and into long-term housing. The issue, Healey has argued, is of federal creation and requires federal solutions.

Emergency regulations issued earlier this week allow the state’s housing department to set a limit on families’ emergency shelter stay so long as a month’s notice is provided to allow for public comment on the policy change.

A spokesperson for the Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities said no action has been taken so far to put in place time limits and guidance issued Tuesday does not address the matter. But the spokesperson said the administration does retain the ability to do so.

Mark DeJoie, CEO of North Shore human services provider Centerboard, Inc, said the idea of time limits may sound “draconian.”

“The timeline sounds like we’re heading to a cliff and once you hit that cliff, you’re gone. That’s not what I’m suggesting. I don’t think the people that I’ve talked to on the provider side, that’s not what they mean,” he said. “But at some point, we all have to understand that shelter is not meant for five to nine years.”

DeJoie said he does not want a hard time limit for families like at “12 months, ‘I’ll see you later.’” The conversation, he said, does need to shift to helping people exit emergency shelter into supportive, long-term housing as quickly as possible.

Massachusetts is required by law to provide homeless families with children and pregnant people temporary housing, whether in traditional sites or pop-up locations like hotels and motels, pursuant to the 1983 right-to-shelter law.

As the number of families in shelter skyrocketed, the Healey administration moved last month to implement a maximum capacity and waiting list, which almost immediately drew a so-far unsuccessful legal challenge from Lawyers for Civil Rights.

Aid organizations and legal groups have warned of dire consequences once shelters are full and families are placed on a waiting list that breaks down prioritization into four different levels, with the top covering those at “imminent risk” of harm due to domestic violence, among other conditions.

Between 150 to 250 people, mostly Haitian parolees, visit the International Institute of New England office each day, Thielman said. The organization is “trying to figure out what we’re gonna do” when there is no more room in emergency shelters, he said.

“We’re certainly not going to encourage them to stay on the (Boston) Common,” he said. “I think we’re going to see in a few days, maybe by next week, we’re going to see a pretty dire situation with lots of people being homeless, and its families who are homeless. And so it’s not acceptable. And honestly, I’m very worried about it and I don’t have a solution right now.”

A waitlist is a “natural” step once the shelter system is full, DeJoie said.

“I’m not sure if everybody believes (us) about the availability of units,” he told the Herald. “If I had 10 section eight vouchers or MRVP vouchers, I don’t know where I’d find those units. There’s nothing about the availability of units that I think is contrived.”