What’s Driving the Shortage of Home Healthcare Workers in NY? Low Wages, Advocates Say

“People who do this work love it. You have to love working with people,” says State Assemblymember Karines Reyes, who is a nurse. But she adds, “If you can get a job doing work that’s not as heavy and not as demanding and make more money, why wouldn’t you?”

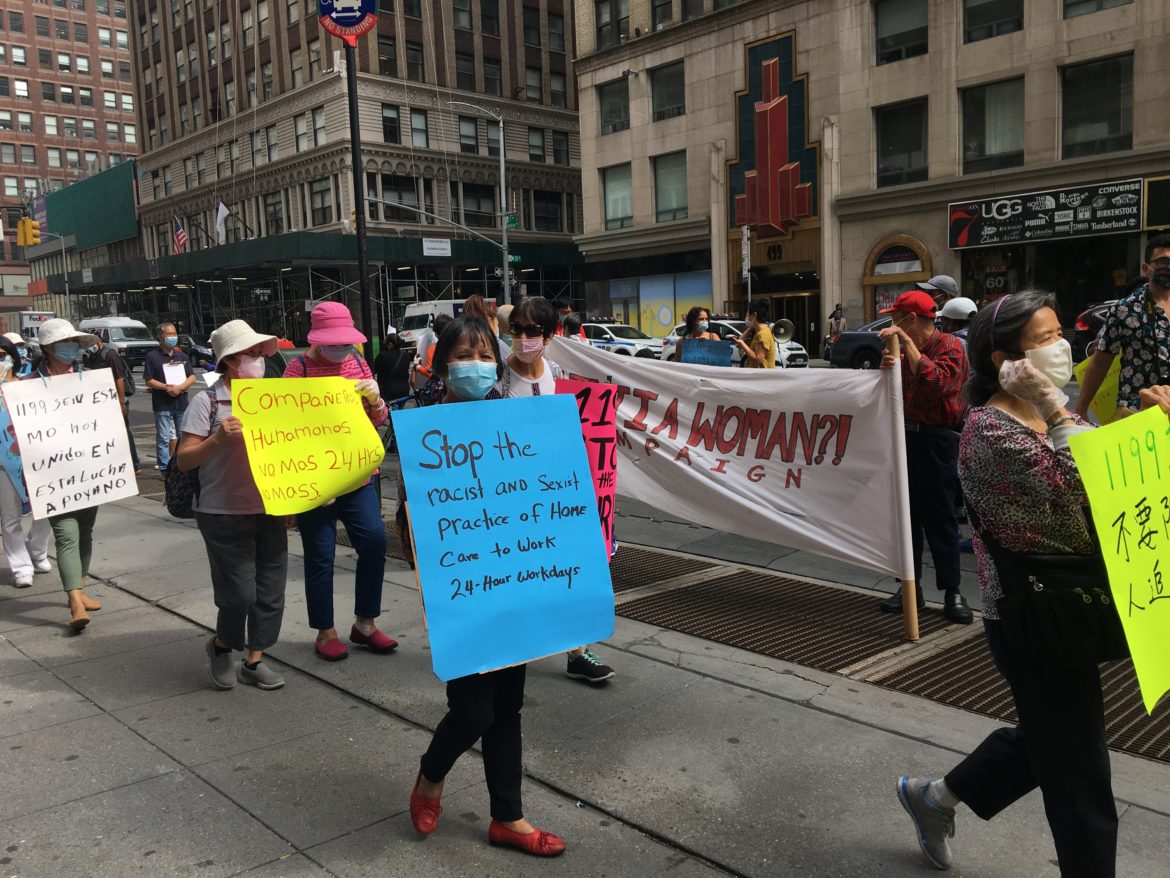

Adi Talwar

On a -ecent mid December morning, Marilyn Thomas feeds Nancy Brown her lunch. Thomas has been a home health aide to Brown since 1997.

Nancy Brown and Marilyn Thomas have been together for 24 years. Brown, who just turned 80, has been severely disabled since she was 7. Thomas, Brown says, “has to take care of me because I can’t take care of myself.”

Thomas said she has kept her job as a home health aide all this time because Brown is “very much a pleasure to work with.” In general, Thomas enjoys taking care of people, cooking and cleaning—the tasks she does for Brown. Doing this work, Thomas said, “makes my day.”

But not many people are willing to do the kind of work Thomas does—not because they don’t want to, but because they can’t afford to. Almost three quarters—74 percent—of New Yorkers needing home health aides were unable to retain a worker in 2021, according to a report by the Consumer Directed Personal Assistance Association of New York State (CDPAANYS). The shortage forces many older and disabled people to go without the care they need, or remain in hospitals and nursing homes.

With New York’s population aging and many older people opting to “age in place”—i.e. not in a nursing home—the demand for workers is expected to grow. Mercer, a consulting firm, has projected the state will face a shortage of 83,000 home health workers in just three years, the worst such shortage in the country.

Almost everyone agrees that low wages are a key reason for that. Home care workers in New York City made an average of $15.93 an hour in 2020, a report by City University of New York found. This falls far below what experts consider a living wage of $21.77 for a single adult in New York City, let alone for a person with children. Put another way, the average annual home health care salary in New York state is $28,220, according to one survey.

People do not apply for the jobs or, if they do, may turn down the position once they learn what the salary is, experts say. Or they may stay for a short time before moving on to something more lucrative or easier, such as working in a fast food restaurant. The CDPAA report found that 20 percent of people with home health aides in 2021 saw the last five of them quit the job, up from 2 percent in 2017.

COVID-19 certainly played a major role, said Bryan O’Malley, CDPAANYS executive director, with people quitting because they didn’t want to take the risk, or because they needed to care for their own children or a sick person in their household. Despite that, almost 50 percent of the clients responding to the association’s survey said a home health aide had quit because of low pay, or having found a better job. “COVID definitely made the situation worse, but it was already a crisis,” O’Malley said.

Often, the aide is reluctant to leave. “People who do this work love it. You have to love working with people,” says State Assemblymember Karines Reyes, who is a nurse. But she adds, “If you can get a job doing work that’s not as heavy and not as demanding and make more money, why wouldn’t you?”

The fight for better pay

Tracey Patterson, a home care worker from Queens, faces that dilemma every day. She says she enjoys her job but must pay rent, support three children, one of whom has special needs. “I don’t want to change to doing something else to take care of my family,” she says, but thinks that she might have to.

Brown, who lives on Roosevelt Island, has three attendants providing her with the round-the-clock care she needs. She would like to find a fourth but can’t. Other people with disabilities have a similar problem. “That’s all we ever talk about when we get together—how hard it is to find good people,” Brown says. “To get good people, we’ve got to pay them better.”

That means the state would have to pay them better, since Medicaid covers almost 90 percent of all personal care cases in New York. Advocates, many under the umbrella of NY Caring Majority, are pushing for passage of the Fair Pay for Home Care Act. Proposed by Richard Gottfried of Manhattan in the State Assembly and Rachel May of Syracuse in the Senate, it would pay home health care workers 150 percent of the minimum wage. For now that would be $22.50 an hour in New York City, for a yearly wage of about $40,000.

Setting the rate as a percentage of the minimum wage is crucial, supporters say, because as the minimum wage has gone up, pay for home health aides has not kept up. Fast food restaurants and similar positions now pay as much or more than home health care agencies and clients. With the labor shortage, some traditionally low-paying businesses have raised their pay, but the state, which sets the Medicare reimbursement for most home health workers, has not followed suit.

“This crisis has been created by stagnant wages in this sector,” says Meghan Parker, advocacy director at the New York Association on Independent Living, who attributes some of the problem to former Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s efforts to reduce the cost of long-term care. “There are just a lot easier jobs. Flipping burgers is a lot easier than going into someone’s home and doing the most intimate care.”

While not a silver bullet for the worker shortage, many advocates see raising the pay as pretty close to one. The state faced a similar crunch about 15 years ago and raised the wage to $10, which was then 162 percent of the minimum wage, according to O’Malley. “The shortage disappeared almost overnight,” he said.

Supporters say raising wages will also go at least a small way toward recognizing and protecting workers performing a vital task, who are overwhelmingly female and people of color. More than 60 percent are immigrants. Despite their being employed, PHI, a non-profit that works to improve care, found that more than half of home care workers in New York State rely on some public assistance.

Reyes would like to see them get an even larger raise than the current legislation proposes. “It should be more because that home-care worker is the difference between life and death,” she said. “If you were to ask people the price of their independence, they’d say it’s a lot more than $22 an hour.”

The Home Care Association of New York State, which represents home health agencies, has concerns, however. While agreeing that “there is an absolute workforce crisis in home care and health care broadly,” HCA’s Alexandra Fitz Blais says, “The big picture should really be considered when looking at solutions.”

“Simply increasing wages is not the long-term solution or a sustainable solution,” she added. Her members also fear that passing the extra money along to workers, without any additional compensation for the agencies that employ many of them, places a burden on those agencies.

The CUNY report estimates a raise similar to the one proposed in the bill would cost the state under $3 billion a year. But it also anticipates a number of benefits that would more than offset that: increased spending by the workers getting higher pay, additional tax revenues and less money paid to workers in public assistance.

A similar measure was introduced last year but failed to make it through the budget. Advocates are hoping increased attention to the problem, and Cuomo’s departure, will make a difference. NY Caring Majority hopes Gov. Kathy Hochul will include money for the increase in her executive budget next month and promote it in her State of the State speech.

So far, Hochul has not taken a position on the legislation.

Picking up the slack

The home health aides shortage has ripple effects—for clients, their family, friends and neighbors, and for other health care providers. The city’s Department for the Aging estimates that some 900,000 to 1.3 million New Yorkers each year serve as unpaid caregivers to family or loved ones, about half of whom spend at least 30 per week providing that care; Many are older adults themselves, and lack the training to formally fill such a role.

READ MORE: Opinion: Unpaid Family Caregivers Need More Support

Loretta Copeland, 81, of Harlem, has an array of medical problems and is confined to a wheelchair. “I need the help because there’s so much I can’t do,” she says. She is authorized to have an aide five days a week but hasn’t been able to find that support, even though she herself worked for many years in the health field.

Copeland had to let one worker go because she would not get a COVID vaccine, and her remaining aide cannot always come. “She’s an older lady and she has her own problems,” Copeland said.

That means Copeland must rely on friends and family, and go without things she needs or risk endangering herself. “I try to do what I can do. I do a little bit and lay down and then do a little bit more,” she says. One day she could not get out of her bathtub, even with the help of a family member, and was stuck until the relative’s husband could provide extra assistance.

But Copeland understands why people won’t take the jobs. The work is strenuous, there are no benefits and the salary is low. “People are not going to come. They’re going to find other ways to make money,” she said.

The shortage can mean older and disabled people find themselves in nursing homes, even if they’d rather stay in their homes. Using federal government figures, Parker has calculated that about 10,800 New Yorkers want to leave their nursing homes but can’t because they can’t find a home health worker. Others find an aide who promptly quits. Then, Parker said, “A person who’s just been given their freedom winds up back in a nursing home.”

Hospitals sometimes cannot release patients because no one is available to help them recover at home. “This is an added cost to the medical facility and disruptive to the well-being of the patient,” said Reyes, a sponsor of the bill. “We need to get people out of hospitals.”

Beyond pushing for the Fair Pay bill, advocates had been hoping for passage of the national Build Back Better legislation. The version passed last month by the House of Representatives would provide $150 billion to reduce waiting lists for home care services and improve pay for home care workers, but the package’s fate remains uncertain.

Besides wages, advocates say there are other ways to address the worker shortage, such as providing better benefits to aides, including health care and time off, as well as properly reimbursing them for all the hours they work.

READ MORE: Company Settles With Home Health Aides Seeking Unpaid Wages For Round-the-Clock Care

“Wages are a primary concern for both workers and job seekers,” said Stephen McCall, data and policy analyst at PHI. But he also sees improved training and opportunities for job specialization and advancement as essential. “We need to think about job quality holistically,” he said.

Home care in the age of COVID

The campaign for better wages and conditions for home health aides comes less than two years after New Yorkers banged on pans every night, and sang the praises of these same “essential workers.” Although the shortage of workers had been building prior to COVID-19, the pandemic exacerbated it and brought it into focus, as nursing homes and other congregate care facilities turned into hot beds for the virus.

People became more reluctant than before to go to residential facilities as “everyone got a firsthand look at how undesirable nursing homes are,” says O’Malley.

But for residents in need of care, remaining at, or returning home, became more difficult. Workers left their clients—because they had no childcare, were sick themselves or had to care for relatives who were, or feared going out.

Deborah O’Bryant, 66, has been caring for the same person, now 97, for years, and continued to do so during the pandemic. In the depth of it, she says, no one else was out on the street as she traveled to her patients wearing two pairs of gloves, two masks and sunglasses to protect herself.

Even her client wondered why she did it. She says she has grown attached to her client—“she’s like a mother to me, like a sister”—and that she enjoys the work, although it is hard. “I care about people. I have a caring heart,” O’Bryant said. What’s more, she needs to support herself, and wouldn’t know what to do if she followed her son’s urging to retire.

During the pandemic, O’Bryant says, workers such as herself “were the doctor, the nurse and the home health aide.” O’Bryant thinks the aides deserve some kind of back pay for what they went through then, but she wonders if the state will even vote for the raise to $22.50.

“These politicians really need to look into it,” she said. “If we all stop working, who’s going to take care of the clients?’