Five things to know about Maryland’s investment in the Orioles and Ravens

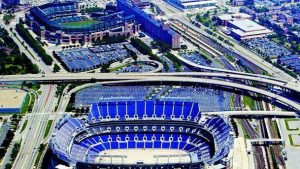

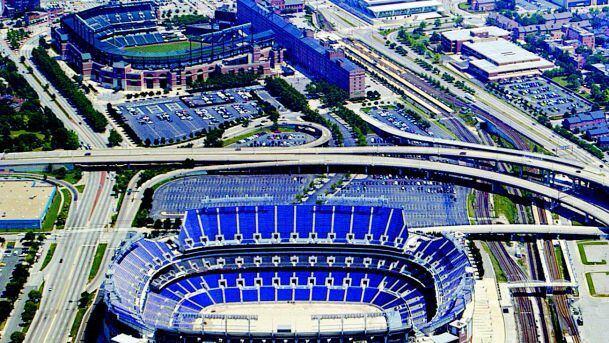

Two of Baltimore’s most recognizable buildings and brands are its two pro stadiums, Oriole Park at Camden Yards and M&T Bank Stadium, and the teams that inhabit them.

The Orioles and Ravens bring attention, pride and joy to Maryland — and Maryland gives a lot of taxpayer dollars back to the teams.

A large public investment

The state of Maryland built and financed both of the Baltimore stadiums and, last year, agreed to earmark at least $1.2 billion to improve the stadiums — $600 million for each. The principal and interest on the bonds sold to cover those costs ultimately would be paid off with lottery revenue.

The Orioles, whose lease with the state expires Dec. 31, are currently negotiating a new lease with more state resources.

According to a Baltimore Sun review of financial documents obtained in public records requests and interviews with experts, the MLB club has received or is on track to get at least $1.3 billion in public benefits since Oriole Park opened in 1988.

That figure includes $450 million in construction and financing costs and $125 million to help maintain the stadium, plus the pending $600 million for ballpark renovations. An estimated $121 million in property taxes were not collected because Camden Yards is state-owned. It does not factor in capital expenditures at the ballpark, which the Maryland Stadium Authority declined to provide.

The Ravens, who signed a lease earlier this year, also have received substantial public support. By signing a lease earlier this year, they unlocked their $600 million in state investment and will renovate their stadium over the next few years.

The next Orioles lease will be a better deal, officials say

The Orioles pay rent to the state each year, but among the reasons for Maryland’s ballooning investment in the team is that the ballclub’s rent does not cover the cost of maintaining and operating the stadium. As part of their current lease, the state pays for upkeep of the ballpark.

In fact, the arrangement has favored the Orioles in every year from 1993 to 2002, leaving the state to pay $125 million more than what it’s received in rent, according to financial information provided by the stadium authority.

An agreement outlined in a memorandum of understanding that the Orioles and stadium authority signed in September aims to “save the state money and reduce risk” by letting the Orioles take on those operating costs and, in return, stop paying rent, said David Turner, a senior adviser and communications director to Maryland Gov. Wes Moore.

Over the past decade, the state has paid more than $6 million annually in upkeep, a cost they would no longer have to pay under the potential new arrangement.

Still, the state would be on track to contribute to the Orioles with a new $3.3 million annual “safety and repair fund,” according to the memorandum.

The memorandum also proposes leasing the B&O Warehouse and other land near the ballpark to the Orioles for an average of $950,000 a year for 99 years in a redevelopment deal that economists have said is favorable to the club.

Economists question stadium subsidies

Some economists believe that the overall benefit from public investment in sports teams rarely pays off.

“The state of Maryland has almost certainly not received an adequate return on its investment in the Orioles in economic terms,” said Brad Humphreys, a West Virginia University economist. “That’s no different from any other professional sports team in the country, but we still continue to subsidize pro sports teams like this.”

According to the stadium authority’s 2022 budget briefing to legislators, the state has received $600 million in taxes from spending related to the Orioles over the three decades of Oriole Park’s life. Those taxes were generated by roughly $9.2 billion in spending during that time.

Economists, however, argue that the economic impact of pro teams is misleading. In particular, they explain that if fans did not attend games, they’d likely spend some of their dollars on other entertainment that would generate tax revenue and economic impact.

Seven economic impact reports by Crossroads Consulting Services, commissioned by the stadium authority and obtained by The Sun through a records request, show that between the 2014 and 2021 baseball seasons, state taxes generated by the Orioles averaged $15.6 million per season.

That figure includes personal and corporate income taxes as well as sales taxes, but not admissions taxes on tickets to games. The authority redacted those numbers, citing confidentiality, but mistakes made in redacting the records helped reveal those numbers for some years — including $5.2 million in admission taxes when attendance at Orioles games was relatively high in 2017, and $3.2 million when attendance slumped in 2019.

Public investment in teams is common in US

Public investment in privately owned sports teams is not unique to Baltimore: About three-quarters of the money spent over the past 50 years to build Canadian and American pro stadiums came from public coffers, per a 2022 study. That is not the case in Europe, where soccer stadiums are generally privately funded.

And more than two-thirds of MLB, NFL, NBA and NHL teams do not pay any real property taxes, according to research by Geoffrey Propheter, a University of Colorado Denver professor of public affairs.

The Tennessee Titans currently play in a stadium built in 1999 — making it newer than M&T Bank Stadium — but will have a new $2.1 billion home in the coming years. Of that, an estimated $1.26 billion will come from public funds and the rest from the Titans. The Buffalo Bills will soon play in a stadium costing an estimated $1.7 billion, which will be paid for by both team and public dollars.

The Tampa Bay Rays are splitting costs for an upcoming ballpark, too, while the Milwaukee Brewers recently made a deal with the state to receive about $500 million in government support for ballpark improvements (in addition to $110 million from the team).

“The Brewers have decided that they need additional cash, and we are falling for that,” Wisconsin Sen. Chris Larson, who voted against the bill, told fellow legislators earlier this month.

The status of state’s leases with teams

The Ravens signed a lease in January, extending their commitment in Baltimore by 10 years (from 2027 to 2037, plus two five-year options) while the Orioles remain in negotiations with the state. That lease is expected to be a much longer term, as the memorandum detailed a 30-year lease with two five-year options.

A new lease would need approval from the stadium authority’s board and the state’s Board of Public Works. Only one more regularly scheduled meeting of the Board of Public Works — on Dec. 13 — is left before the end of the year, when the Orioles’ lease ends.

The board, which consists of Moore, Comptroller Brooke Lierman and Treasurer Dereck Davis, who are all Democrats, could call a special session after that, though the governor did not answer when asked by a reporter Wednesday when he expected the deal to be ready for a vote.

Asked about the tight timeline, Moore said only that “the MSA and the state are literally working around the clock with the Orioles” and that the parties “have a few weeks to finalize what the next steps are going to be.”

Two people with direct knowledge of the discussions told The Sun that negotiators are considering separating the issue of the development rights from the lease extension.

Moore did not specifically confirm that possibility when asked. What’s important, he said, is accomplishing his previously stated goals of keeping the Orioles in Baltimore for the long term, using the deal to benefit the local economy and getting a fair deal for taxpayers.

“Honestly, the only thing that matters to me is that my three objectives are hit,” Moore said. “How we are packaging that, honestly, that is less relevant.”

Baltimore Sun reporter Jeff Barker contributed to this article.

()