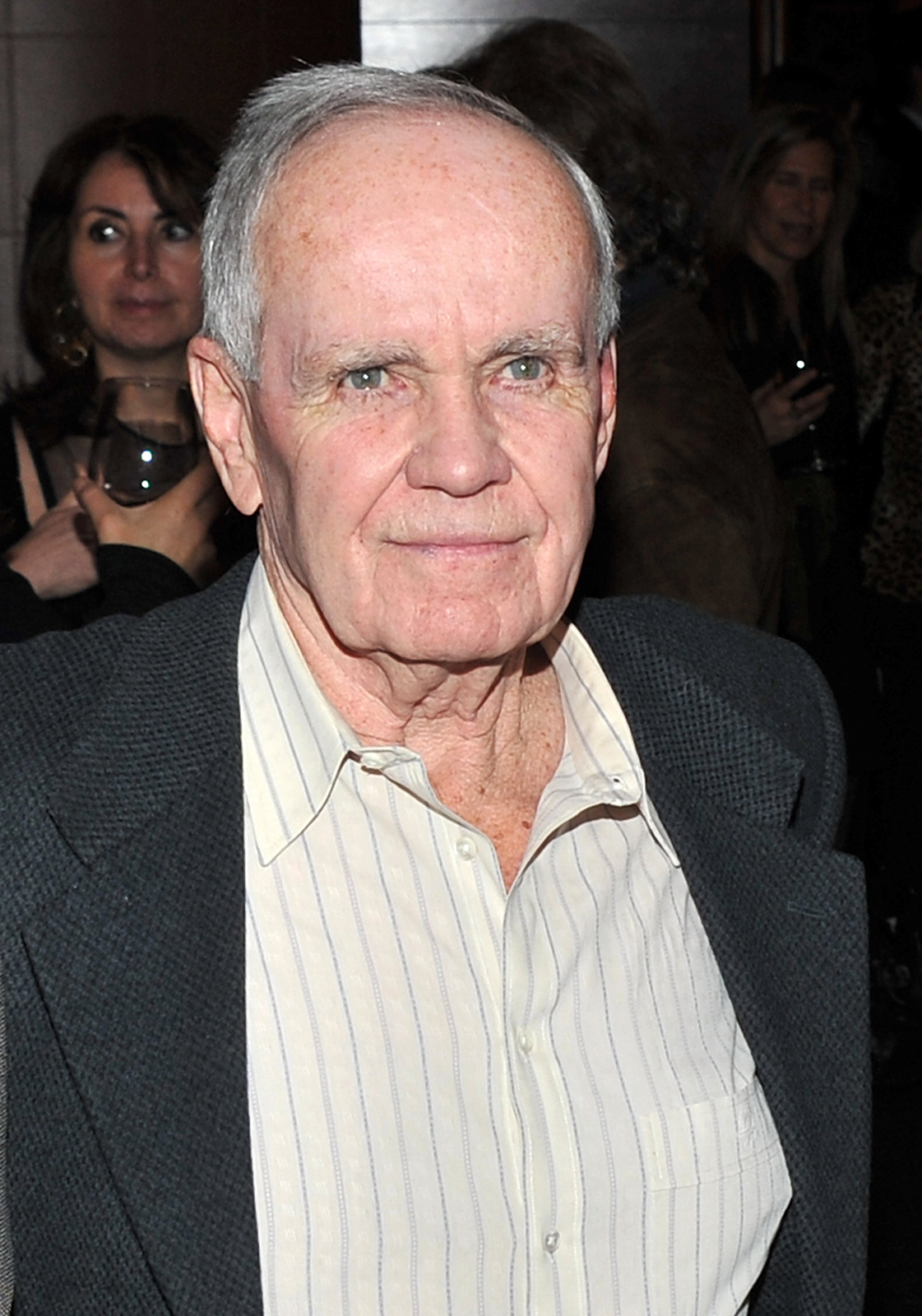

Cormac McCarthy’s teen muse breaks silence

Great American novelist Cormac McCarthy was defensively private and didn’t share much about the inspiration behind his books — or about himself. However, the author, who died in 2023, apparently lived out much of his bestseller “All the Pretty Horses” with a woman named Augusta Britt.

She was 16 when she met the then 42-year-old writer in 1976.

Britt, now 64, guarded her identity and her story for nearly five decades, publicly revealing herself as the author’s “single secret muse” in a Vanity Fair profile published this week. Writer Vincenzo Barney argues that many of the Pulitzer Prize winner’s leading men were inspired by Britt, a “five-foot-four badass Finnish American cowgirl … whose reality, McCarthy confessed in his early love letters to her, he had ‘trouble coming to grips with.’”

Britt’s story has “always been there, below the surface, between the lines in the novels’ coy subconscious,” Barney writes. She had a strong presence throughout “The Road” author’s acclaimed “Border Trilogy,” inspired Carla Jean in “No Country for Old Men,” was Alicia in “The Passenger” and a nurse named Wanda in “Suttree.” Horses identical to her breeds appeared in the 2013 film “The Counselor,” in which Penélope Cruz plays a character based on her.

“Cormac always wanted me to tell my story,” Britt said. “He always encouraged me to write a book. He’d say, ‘Someone will do it eventually, and it might as well be you.’ But I just never could bring myself to.”

Barney said he connected with Britt after she left him a pointed comment on his Substack review of McCarthy’s 2022 novel “The Passenger” — a review that McCarthy told her “something good will come of.” Then, she sought out Barney, insisting on speaking only to him rather two other McCarthy biographers vying for her attention.

She invited Barney to Tucson, Arizona, to hear her story, and they spent nine months together. McCarthy, she said, had warned her that she “couldn’t hide forever,” and she readily shared 47 (occasionally erotic) love letters the “Blood Meridian” scribe wrote to her that illuminated their relationship and, in McCarthy’s own words, his “undying devotion.”

Britt said she’d been “so afraid” to tell her story — after all, who would believe her? But he had warned her that one day his archives would open and people would learn about her.

Britt also inspired the slapstick sidekick Harrogate in “Suttree,” which McCarthy was writing when they first met at a Tucson motel swimming pool where she went to safely shower away from her foster home.

She was in foster care in Arizona after she experienced “a traumatically violent” event that destroyed her family and returned to the hotel to ask McCarthy to sign a copy of his 1965 debut novel, “The Orchard Keeper.” McCarthy, she said, wanted to know why she was wearing a holster with a Colt revolver in it. It turns out she had stolen it from the man who ran the foster home. She also had a stuffed kitten named John Grady Cole, the hero’s name in McCarthy’s “The Border Trilogy,” which follows three runaways who have a stolen Colt revolver.

“It was the first time someone cared what I thought, asked me my opinions about things,” she said. “And to have this adult man that actually seemed interested in talking to me, it was intensely soothing. For the first time in my life, I felt just a little spark of hope.”

Growing frustrated with issues in Britt’s personal life, McCarthy tweaked her birth certificate on his typewriter so she could run away with him to Mexico. It worked but left trouble for both of them in its wake.

The optics of their three-decade age gap weren’t ideal for them either. Despite characterizations of premeditated grooming, Britt asserted that she felt safer with him than with any of the many men in her young life at whose hands she had, in Barney’s words, “suffered unspeakable violence.” McCarthy — who was married to the second of his three wives, singer Annie De Lisle, when he met Britt — still worried about statutory rape allegations and the Mann Act in the early days of their relationship.

She said that he was 43 and she was 17 when they first had sex.

“I can’t imagine, after the childhood I had, making love for the first time with anyone but a man, anyone but Cormac. It all felt right. It felt good,” she said. “I loved him. He was my safety. I really feel that if I had not met him, I would have died young. What I had trouble with came later. When he started writing about me.”

She said that McCarthy’s letters, many of which she received before they consummated their relationship, made her uncomfortable at the time because they were so different from how he talked on the phone or in person. But, she insisted, she never felt anything inappropriate about their relationship and was more concerned McCarthy would be misunderstood by the wider public if she came forward.

“One thing I’m scared about is that he’s not around to defend himself,” she said.

About two years into their relationship she learned that he was married. About a year later, she learned that McCarthy had a son who was about her age.

“It just shattered me. What I needed then, so badly, was security and safety and trust. Cormac was my life, my pattern. He was on a pedestal for me. And finding out he lied about those things, they became chinks in the trust.”

Britt left him about three years into their relationship. They continued to keep in touch, talked regularly for years and saw each other when he visited Tucson. When McCarthy sent her the manuscript for “All the Pretty Horses” in the 1980s, she was confused by how much the novel was “full of me, and yet isn’t me.”

“I was surprised it didn’t feel romantic to be written about. I felt kind of violated,” she said. “All these painful experiences regurgitated and rearranged into fiction. … I wondered, Is that all I was to him, a train wreck to write about?”

Britt said she declined two marriage proposals from McCarthy and lamented how nearly all the characters she inspired him to write died. But, she said, after decades she realized he was “killing off the darkness” of what happened to her.

“Those things that happen to you, that young and that awful, you don’t really heal. You just patch yourself up the best you can and move on.”

©2024 Los Angeles Times. Visit latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.