What Bradley Cooper’s ‘Maestro’ reveals about Leonard Bernstein — and Cooper’s own artistic ego

The billing seems a little off once you’ve seen “Maestro,” now in limited theatrical release ahead of its Dec. 20 Netflix streaming premiere. But we’ll get to that.

Cooper’s second directorial feature, which had its world premiere at the Venice International Film Festival in September, follows the massive success of his remake of “A Star is Born” five years ago. There, as the whiskey-soaked country star on the way down, the actor lowered his speaking voice to a warm Sam Elliott growl.

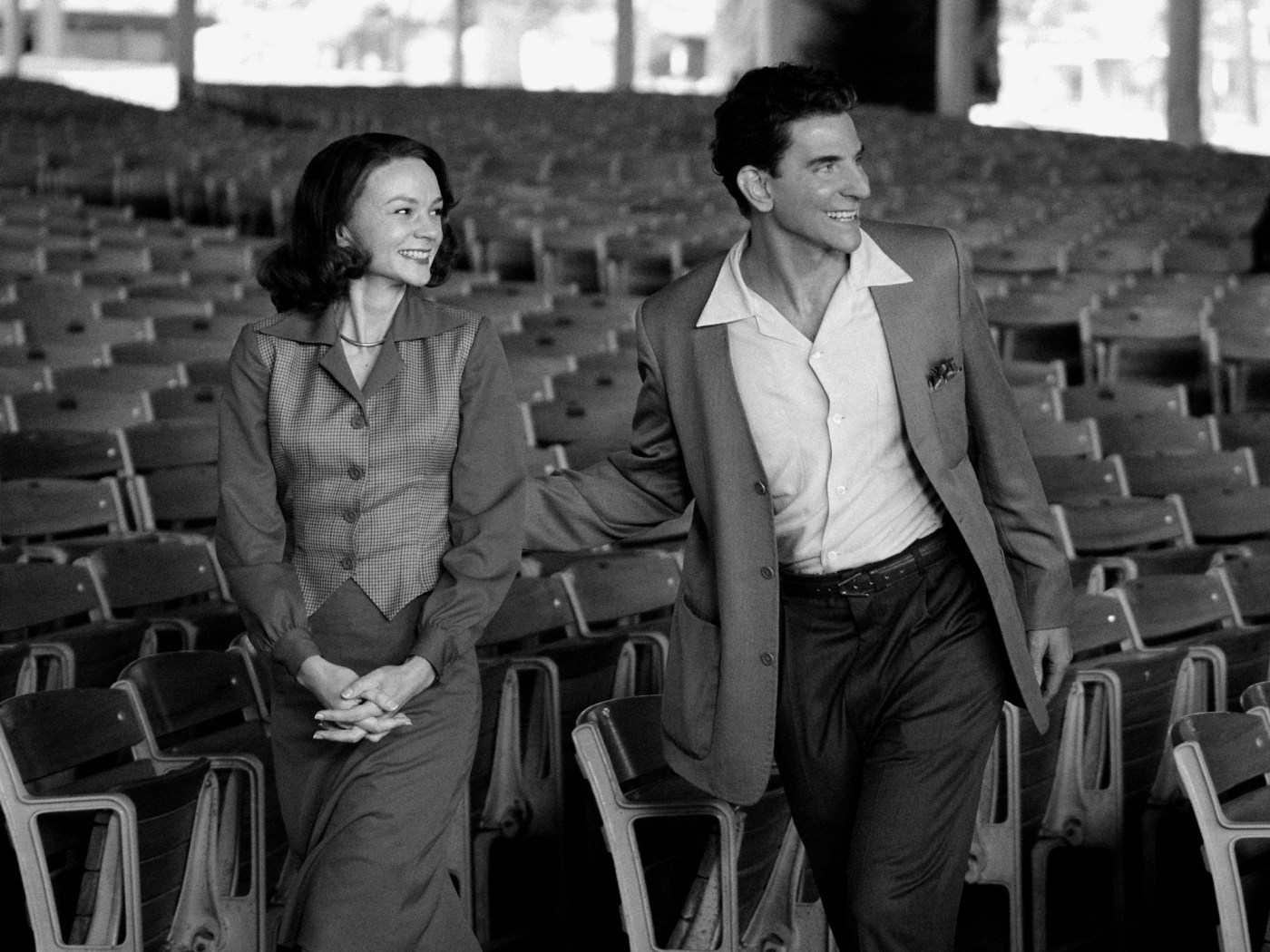

In “Maestro,” working off untold hours of video and audio tapes of his real-life subject, Cooper fashions a higher, faster approximation of Bernstein’s vocal cadence, while various degrees and thicknesses of prosthetic makeup handle the rest. The trick for any actor in these biopic circumstances is making all the externals into a lifelike but not slavishly archival whole.

I’ll review “Maestro” next week closer to the film’s Chicago opening. But after the recent press screening I was eager to sit down with Tribune classical music critic Hannah Edgar and hear what they had to say about it. In 2018 Edgar, also a musician, spent a summer assisting with the curation of the traveling Leonard Bernstein centenary exhibition under the auspices of the New York Philharmonic Archives.

Over coffee we talked about some initial reactions to Cooper’s embodiment of Bernstein; the focus of this version of his life; and the filmmaker’s reported six-year preparations for the film’s centerpiece conducting scene, depicting Cooper-as-Bernstein’s “antic” (Edgar’s word) attack on Mahler’s 2nd Symphony, photographed in a single take.

“Maestro” begins in 1943, in black-and-white, with a 25-year-old Lenny, in bed with a male lover, receiving the early morning phone call of his career: He has been tapped to substitute, with zero rehearsal time, for an ailing Bruno Walter. This marks Bernstein’s momentous debut with the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall, and lights a fire underneath his already roiling ambitions.

The following has been edited for clarity and length.

Michael Phillips: Hannah, a year ago we talked about “Tár” when that came out, and I came away a lot smarter than when I went in, thanks to you. I wonder if there’s any film dealing with a conductor or a composer or any sort of musician that came to mind while we were watching “Maestro” the other day?

Hannah Edgar: The one that came to mind, honestly, for better or worse, was that really trippy Mahler movie from the ‘70s —

Phillips: Ken Russell’s “Mahler”! Trippy’s the word, all right.

Edgar: I remember seeing that in high school. And what that movie did successfully, at least for me, that parts of “Maestro” also does successfully, is instead of sort of rotely taking you through the beats of an individual’s life, it explored how their music makes you feel. For me the fantastical elements of “Maestro” were the strongest. And to see them more or less abandoned halfway through, once the movie turns to color, was kind of a letdown for me. In the early black-and-white scenes we see Bernstein’s life taking place (metaphorically) almost as if he lived in the wings of a theater, or a concert hall.

Phillips: Right, and it’s almost a full-on musical or ballet, when Bernstein and Felicia are on this sort of fantasy first date, scored to Bernstein’s “Fancy Free,” and at one point Bernstein’s actually dancing part of it himself, in a sailor costume. There’s also a bit of Bernstein’s “Lonely Town” ballet music from the Broadway musical “On the Town,” inspired by his work with Jerome Robbins on “Fancy Free” earlier that same year (1944).

I do think “Maestro” is going to introduce some great music to a lot of people who haven’t heard it yet. Tell me more about what did and didn’t work for you here.

Edgar: I did love a lot of the details. They lived at The Dakota at 72nd Street and Central Park West in New York, right along the parade route for the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, and I loved seeing the enormous Snoopy floating by when Leonard and Felicia are having this epic argument.

Phillips: Isn’t that a great screen argument? Why did it work for you?

Edgar: Because it felt true. We know by that point that she’s straining under the weight of Bernstein’s ego, and we know that he has these trysts with various men over the years. But it’s finally out in the open. It just plays out in a way that feels authentic. I don’t know many couples, even if they’re well-adjusted and have a great couples therapist, that can keep an argument entirely civil. Typically when you have an argument there’s a lot behind it, with long-simmering resentments erupting. It’s hard to watch, and usually with scenes like that in the movies, I’m cowering. But this one in “Maestro” is different. It felt cathartic to me.

Phillips: For me, too. That scene doesn’t feel amped up, and it plays out in a long take, no cutting for the usual emphasis. Compared to that scene, parts of the movie feel more routine. But more than you, I think, I basically went for it, even if I had the same feeling watching “Maestro” as I did with “A Star is Born,” which I liked as well — that Cooper, directing himself, has a way of ever-so-shrewdly stealing focus away from his female co-stars.

Edgar: Hundred percent! The “Maestro” trailer, which is great, makes it seem like it’s going to be a biopic told through the lens of their relationship. But the movie starts with Lenny getting the call about his Carnegie Hall debut. I think it would’ve been a more effective and sensitive story if it had been told through Felicia’s viewpoint.

On the other hand: I suppose there’s a self-aware argument Cooper’s making, and it appears in (daughter) Jamie Bernstein’s memoir: that you have to sacrifice yourself at the altar of Bernstein’s ego.

Phillips: Cooper has many more on-screen minutes in the role of conductor than Cate Blanchett did as Lydia Tár. Who’s the better pretend conductor?

Edgar: I’d say Cooper. But Blanchett had the harder job, which was to figure out her fictional character’s own style of conducting.

Phillips: Bernstein has the advantage of being real; there’s so much research material, all the archival video and audio, for an actor to work from. His concerts for young people, the lectures, the televised concerts, all of it. Here’s my question to you: Is what we see in “Maestro” a fully fleshed-out performance? Or more of a studious collection of external mannerisms?

Edgar: I do think Cooper’s seriousness about the research part of it shows in the movie, and people have already written about his apparently taking six years, off and on, to convincingly conduct, as Bernstein, six minutes of Mahler … We see just about every imaginable Bernstein-ism packed into those minutes. As a musician, watching that scene I was thinking: Would I actually be able to follow him? I don’t know. Cooper’s doing the pantomime of conducting. It’s hard to describe. I felt in awe of him as a mimic, but …

Phillips: I think I know what you mean. Cooper is so talented in so many directions, but I don’t know if he’s figured out how to throw away anything casually, even when he should. Mulligan isn’t playing as famous a figure, but man, she’s good. And when the movie does give Felicia her due, it’s worth every second.

Is there any musical biopic cliché that “Maestro” either does or doesn’t avoid that we should talk about?

Edgar: Maybe this: What made Bernstein such a unique creative personality — Jamie talks about it in her book — is that the only thing Bernstein loved more than music was people. And that creates a conflict. There’s usually a narrative of seclusion in the tortured-genius story, but that’s not really Bernstein’s story. He wanted to be in the thick of everything. He thrived on new people, thrived on adoration from the public. And that part, Cooper handles really well. That look in his eyes when he gets his first taste of fame in “Maestro” tees us up for the whole movie.

Phillips: There’s a lot of George Gershwin in Bernstein’s musical drive, at least to my ears — would you say they experienced the same struggle between highbrow and middlebrow music, the concert hall versus Broadway or Hollywood?

Edgar: Totally! He was so simpatico with Gershwin! And they both dealt with antisemitism, and I’m glad that made it into the movie. (As a young conductor) Bernstein was advised to change his last name to Burns. Thank God he didn’t.

Phillips: Let’s end with this question: Could anyone like Leonard Bernstein take a central place in 21st-century popular culture?

Edgar: No. Sad to say it, but I think his story is a period piece. During Bernstein’s life there was a national funding apparatus behind classical music and the fine arts. That funding does not really exist anymore.

———

(Michael Phillips is the Chicago Tribune film critic.)

©2023 Chicago Tribune. Visit chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.