Gaskin: Blacks, Jews must remember shared legacy

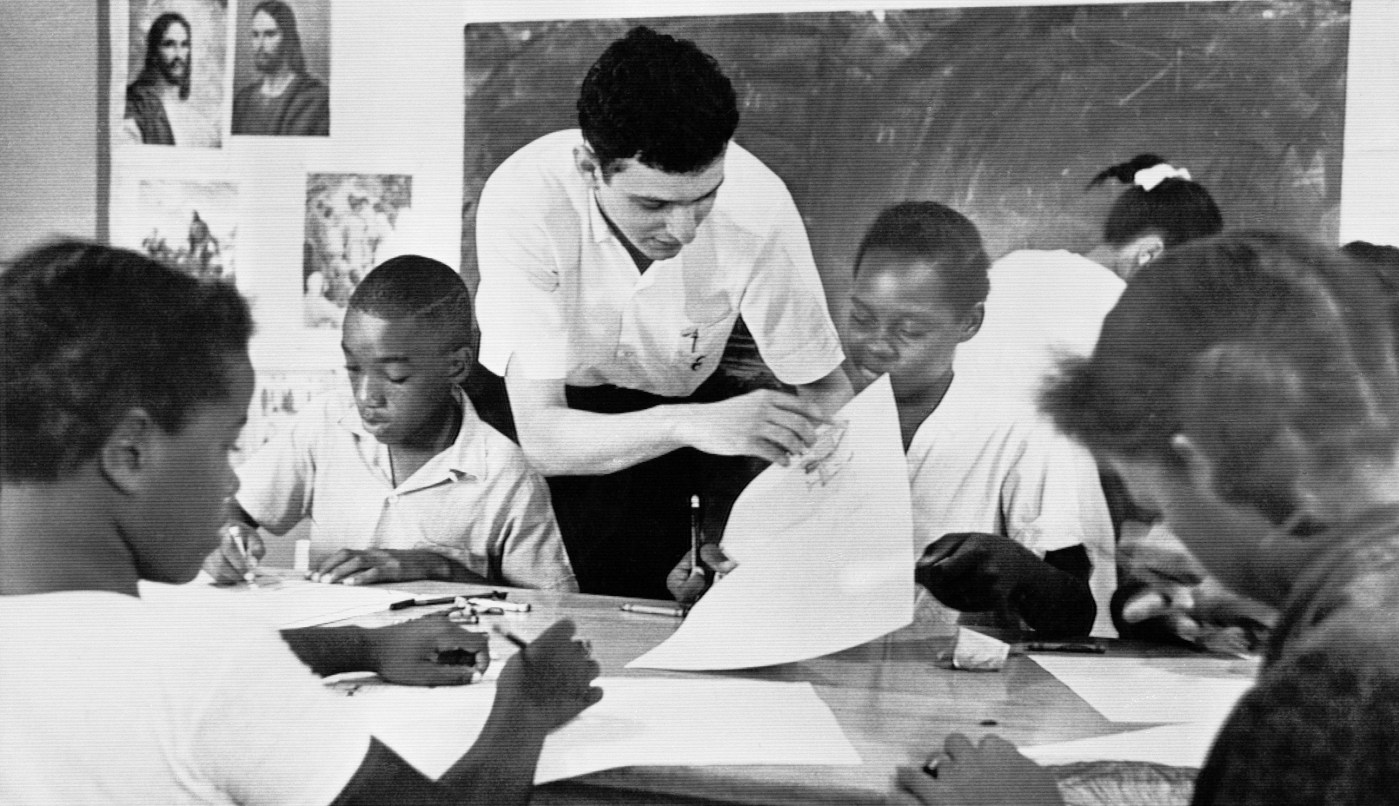

This year marks the 60th anniversary of Freedom Summer, a high point in the alliance between Jewish and Black Americans.

Young people poured into Mississippi in the summer of 1964 to register Black voters. Half of them were Jewish. Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner were murdered along with African American activist James Chaney because of their work.

The connection between Jewish and Black history resonated with Dr. Martin Luther King, who told the American Jewish Congress in 1958:

“My people were brought to America in chains. Your people were driven here to escape the chains fashioned for them in Europe. Our unity is born of our common struggle for centuries, not only to rid ourselves of bondage, but to make oppression of any people by others an impossibility.”

That was then.

As the Martin Luther King Jr. speaker at a Jewish institution, I was asked a poignant and challenging question by a Black woman, the chair of the DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) committee: “Do you feel Jews are racist?”

Her question stemmed from concerns about “Jewish” attacks on DEI initiatives, citing the controversy surrounding Claudine Gay, the first Black person and first Black woman president of Harvard, and the efforts by some Jewish individuals, including Bill Ackman, to see her removed and DEI programs at other universities eliminated.

Despite Gay’s widely criticized testimony before Congress in which she was asked if calls for the genocide of Jews constituted harassment under university policy, responding that it depended on the context, her subsequent resignation has fueled anti-DEI flames.

Initially horrified by the woman’s question, I embarked on a journey of research. What I discovered was a troubling narrative beginning to form— one that could undermine the longstanding alliance between Black and Jewish communities. Many of today’s Black college students are unaware of the rich history of Jewish support for Black civil rights, a history beautifully captured in documentaries like “Shared Legacy” by director Shari Rogers.

For me, the narrative of “racist Jews” started when the only countries supporting South Africa and its apartheid system were the U.S. and Israel. Critics in the U.S. pointed to Nelson Mandela getting support from Yasser Arafat and Fidel Castro. The point made was Israel was supporting the white oppressors and not the oppressed Blacks. And Israel’s internal struggles with racial issues — Jews of color desiring to practice the right of return to Israel or Blacks, mostly Africans, getting fair treatment in Israel.

In the U.S., Black critiques of Jews often echoed the rhetoric of Minister Louis Farrakhan, who propagated the infamous “Protocols of the Elders of Zion ” and referred to Jews as Satanic. Even prominent figures like Angela Davis, who received a Ph.D. from Jewish Brandeis University, have long criticized Israel and supported Palestinian causes.

The slogan “From Ferguson to Palestine,” popularized during the Ferguson, Missouri protests after the shooting of Michael Brown, epitomizes the growing Black-Palestinian solidarity.

Jewish groups have historically supported Black pastors visiting the Holy Land. However, the new trend sees Black pastors and activists touring the West Bank, drawing parallels between U.S. racism and Palestinian segregation. This led to an increased understanding of Black-Palestinian intersectionality. Articles like “The Long, Complicated History of Black Solidarity with Palestinians and Jews” and “From Ferguson to Gaza: How African Americans Bonded With Palestinian Activists” illustrate this shift. The similarity was obvious to anyone who had spent time in the West Bank.

However, other articles pointed out no such similarity existed between racism against Blacks in the U.S. and the Palestinian situation and that such comparisons were dangerous.

More recently, the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL), related to but distinct from Black Lives Matter, issued statements supporting Palestinians. This alignment has positioned Jews and Blacks on opposite sides, with the destruction of Gaza serving as potent evidence for some that Israel aligns with “colonial” oppressors and is part of the system that needs to be replaced.

The Oct. 7 massacre of Jews at a music festival by Hamas terrorists and subsequent evidence of mass rape and other heinous acts committed against them and the hostages were denied or ignored.

The Black/Jewish division is exacerbated by well-publicized opposition to DEI programs from Jewish individuals like Bill Ackman, Marc Rowan, Clifford Asness, and Ron Lauder. Borrowing a technique from shareholder activism, they can either promise to give or threaten to withhold their and other’s donations to schools that don’t change their DEI practices. This opposition helps fuel the narrative of racism, especially when Jews who have historically supported Black causes align with anti-woke, anti-critical race theory, and anti-DEI conservatives. While there may be a few Jews who oppose DEI, it is hardly the position of most Jews, especially those who embrace the philosophy of Tikkun Olam (“repairing the world”).

A significant issue with many DEI programs is their exclusion of Jews as a protected class. Despite Jews making up only 2.4% of the U.S. population, they are the targets of 60% of religion-linked hate crimes, according to the FBI. Clearly, DEI programs need reform.

Yes, the 20th century saw strong Black-Jewish alliances. But there’s also a history of tension between Blacks and Jews, particularly in urban areas with landlord disputes and conflicts with shopkeepers. Working at Jewish investment banks like Salomon Brothers or Goldman Sachs often mirrored experiences at non-Jewish firms. Jews of Color frequently highlight the racism within the Jewish community, pointing to the marginalization of Ethiopian Jews and the lack of representation during Black History Month.

At a Black-Jewish ally event, a Black pastor confided in me: “Until Jews are ready to have an honest conversation about race and racism, this allyship won’t be too deep.”

Opposing some DEI programs does not mean one is racist. There needs to be room for a difference of opinion. There may be a good reason for opposing a particular DEI program. Let’s not take the actions of a few and generalize about a whole group. What we haven’t heard about are the Jewish business people who have opposed or confronted their fellow Jewish business people for attacking DEI programs.

The last thing we need is another Jewish trope. We must remember our shared legacy and recommit to building a just and equitable society.

Ed Gaskin is Executive Director of Greater Grove Hall Main Streets and founder of Sunday Celebrations.