‘From St. Paul to the Hall’: Paul Molitor steals home

Editor’s note: On Sunday, Joe Mauer will become the fourth St. Paulite inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., building on a legacy begun by Dave Winfield, Paul Molitor and Jack Morris.

The Pioneer Press has chronicled the remarkable careers of these local legends since they were little leaguers.

And as we count down the days to the induction ceremony, we’re revisiting our coverage of the Saintly City’s Hall of Famers, publishing an article from our archive on each one. Today is Paul Molitor.

Our new book, From St. Paul to the Hall, digs even deeper into the careers of these four special ballplayers. You can pre-order your copy at store.twincities.com.

This article appeared March 31, 1996.

He has lived the highest highs and the lowest lows. From Milwaukee to Toronto, from All-Star Games to two World Series. He has played with the best. He has seen the country.

He has reached the pinnacle of his profession. Inch by inch, foot by foot, scratching and clawing, and moving ahead the only way he knew how, by working his body to the bone. For that, he was named the most valuable player of the 1993 World Series.

Blessed? Paul Molitor can document a case history.

“No question,” said Molitor, still the guy next door after growing up in St. Paul’s Grand Avenue-Pascal Street neighborhood. “I think you learn that so much of what anybody is able to accomplish, really, you just can’t take much credit for.

“I have no control over my ability to play baseball. This is nothing of me. You start looking at yourself as the reason good things happen, I think that’s a little misguided. You try to take whatever good things you do and bring them into fruition.

“I definitely feel I’ve been blessed, from my family to the ability I’ve been given to health … I’ve had the opportunity to do many, many things.”

He is 39 now, closing in on becoming only the 20th player in major league baseball history to collect 3,000 hits. He needs 211, and should reach the milestone early next year.

Yet there has been one thing missing during the past 19 years, one hole in his swing.

And when the Twins open the season against the Detroit Tigers on Monday afternoon, that final piece will be in place.

Paul Molitor is coming home.

“It’s taken us all quite awhile to adjust,” said Carol Rolland, one of Molitor’s six sisters. “Hearing that the Twins’ game is going to be on the radio still doesn’t equate with having Paul here. It doesn’t quite seem real yet.

“We’re very excited to have him close to home. Not just because he’s a famous baseball player, but because he’s our brother, and he’s been gone all these years.”

Isn’t that what baseball really is all about, anyway? Family? Fathers and mothers playing catch with sons and daughters, and watching in the stands at Little League games. Pickup games in the vacant lot next door.

One generation growing into the next, one pitch at a time.

“We’re very excited,” Rolland said. “Not just to see him play more ball, but to spend more time with Paul, his wife and daughter. Do more normal things. Go to his daughter’s school plays. He can come to my daughter’s graduation.

“Or, ‘Hey, Paul, I have some extra spaghetti tonight. Come on over for dinner.’”

Say one thing: With Paul home, the family’s telephone bills are sure to go down.

St. Paul history

As baseball spins wildly through the 1990s toward an uncharted future, certain things — values, morals, take your pick — have disappeared. Sometimes, it seems as if baseball, rather than television, could use that V-chip device with which parents can block out certain things from their kids.

There are contracts to negotiate, shoe deals to study, agents to call. There is more money to scoop up, one last dime to soak from someone, one more market to test.

The thing with Paul Molitor is, he has always remained grounded to St. Paul.

Even during spring training, flights from the Twin Cities have been loaded carrying visitors for Molitor. Wife. Daughter. Sisters. Friends.

“I think this means an awful lot to him,” said childhood friend Denny Roach, who returned to the Twin Cities from Florida last week. “He’s a family person. He loves his roots. He’s really looking forward to this.

“He lived and died a Minnesota Twins fan as a kid. It is really a special point for him.”

Paul Molitor: How the Hall of Famer is easing into role as Twins leader

Out at Northwest Airlines, people have been approaching Dave Molitor, Paul’s brother, nearly every day for the past two months.

“How’s Paul doing?” they ask. “Wow, can’t wait for the baseball season.”

Sometimes it’s one person a day. Sometimes a couple of people. But every day. The anticipation builds.

Related Articles

Justin Morneau excited to see longtime friend, Twins teammate Joe Mauer honored in Cooperstown

Twins release 2025 schedule

St. Paul vs. Mobile, Alabama — which is the capital for Hall of Famers?

Joe Mauer’s 2009 season was legendary. Where does it rank among the best ever?

Speech written, Joe Mauer ‘excited, nervous’ for Hall of Fame induction weekend

“I’ve worked at Northwest Airlines for the past 12 years, and now, suddenly, people are coming up to me and telling me first hand that they’re going to attend more games because things will be more exciting with Paul,” Dave said. “That’s why I think his signing will be a mutual benefit for both sides.”

Around the Twin Cities, the buzz continues.

“I’m surprised that the people who haven’t mentioned it to me in the past have mentioned it now,” Rolland said. “People I work with …

“Paul’s brother and other sisters, our kids, friends, we’re just kind of riding the glory right now in a very fun way. Right now, it’s still front-page news for all of us.”

Dave Molitor plans to spend plenty of time at the Metrodome this summer with his son, Nicholas, 7. And while Paul is studying opposing pitchers, his 11-year-old daughter, Blaire, will be busy becoming reacquainted with her 24 cousins.

“Even when Paul’s wife travels with him, just to pitch in and do family stuff,” Rolland said. “Take care of his dog and hamster.”

The biggest difference Monday, as opposed to 25 years ago, is that when Paul joins the hometown team, he won’t be riding his bicycle to the baseball field.

“Now I’ll just hop on the freeway — and try to find the players’ lot,” Molitor said, grinning.

Oxford playground

Used to be, Molitor’s bicycle was parked on St. Paul’s Oxford playground for what seemed like 24 hours a day.

“I remember when I was young, I would be on at least three teams a summer,” he said. “Every night, I’d be on my bike riding to practice.”

As a teenager, Molitor worked at the Oxford playground. Could there be a more perfect job for a neighborhood kid? He took care of the softball fields, mowing grass, chalking the fields, sticking around, waiting to choose up sides.

Hours later, there he was on the fields with a glove on his hand, chasing baseballs, cracking line drives, one after another as the sun dropped from the summer sky.

Playing on VFW and Babe Ruth teams. Playing for — and winning — state championships while at Cretin High School. Watching Dave Winfield take batting practice in street clothes the summer Winfield came home for baseball’s all-star break as a rookie with the Padres.

“One time when he was a senior in high school, he had mononucleosis and couldn’t play,” said Bill Peterson, one of Molitor’s old coaches, now St. Paul’s supervisor of municipal athletics. “One day he was walking across the field, all mopey, and sat on the bench. He asked me if he could take a few swings, and he put on an exhibition of hitting I’ll never forget. He was hitting the ball 380, 400 feet. It was unreal.”

One afternoon a car clipped the back of Molitor’s bicycle as he was riding barefoot to practice. He got his toes caught in the spokes, cut them and couldn’t play that day. Peterson instituted a new rule: Players must wear shoes on their way to practice.

“Paul was my little brother who we organized our meal times around, our laundry schedule around,” Rolland said. “Even when Paul was in Little League, it was a rallying point for our family. It was what we did. We ate early or late, depending on the game.”

She chuckled at the memories.

“I think the only time we got upset was when we had to cook something special if Paul didn’t like what we were having for dinner. There was always a hamburger to fix Paul if he didn’t like the hot dish.”

Then, the first time Molitor returned to old Metropolitan Stadium as a rookie with the Milwaukee Brewers in 1978, the Twins flashed “Welcome Home, Paul” on the scoreboard.

“I will never forget that,” said Molitor’s father, Richard, who winters in Sun City, Ariz., and spends summer in the Twin Cities. “That sent shivers up and down your spine.

“We were all so excited. That was really something. That was really special, him coming home.

“And now, he’s home again.”

Ambassador to fans

Every day after workouts this spring, a tired, sweating Paul Molitor would trudge from the fields toward the clubhouse, become engulfed in fans and autograph seekers, and plop down on a picnic table.

Once there, he would ask only that the fans be orderly and polite — and then he would sign autographs until

everyone had gotten one. Sometimes it took 15 minutes, sometimes 30, many times longer.

Hot sun. Dripping sweat. Every day.

He is one of baseball’s best ambassadors. Need an autograph? If at all possible, Molitor will oblige. Those fans calling out to the players from the first rows by the dugout? If it’s before a game or during batting practice, Molitor will unfailingly acknowledge them.

When the Twins played the Japanese Olympic team early in the spring, Molitor led his team onto the field afterward for the traditional handshake line.

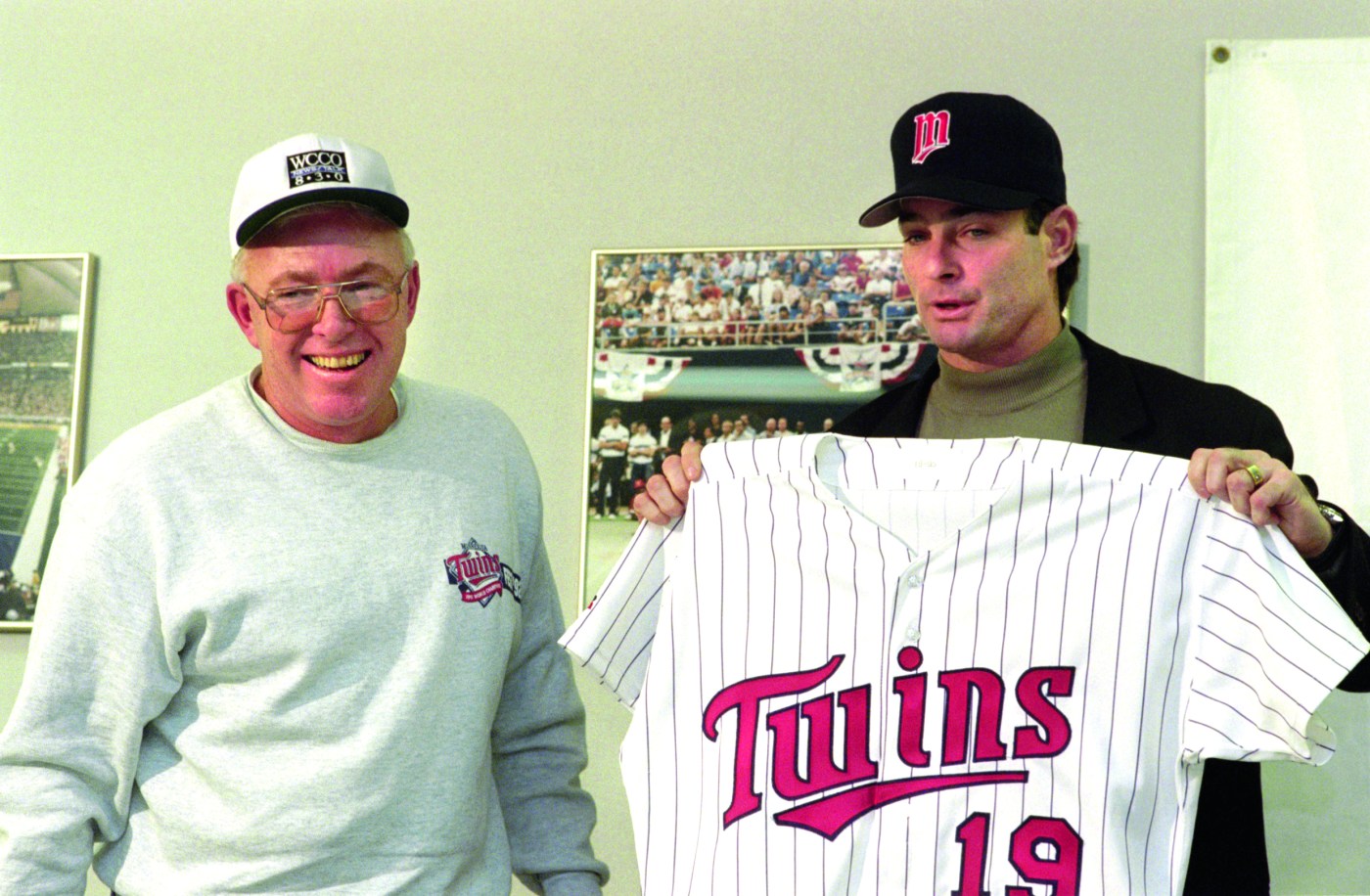

“I’ll say one thing, he sure is cooperative,” Twins general manager Terry Ryan said. “He’ll go out of his way to make people feel comfortable around him. As cooperative and easy to approach as he is, he carries himself like he’s 25 years old. He’s just one of those guys you feel good to be around.”

Ryan shakes his head at the thought of Molitor sitting on that picnic table, day after day, all spring.

“I don’t know if people realize — that’s quite a deal,” he said. “One day here, one day there, that’s one thing. But that was every day … that’s how you bring people back to the ballpark.”

Is it any wonder that Molitor leaves a trail of compliments wherever he goes?

“I’m definitely going to miss him,” Toronto outfielder Shawn Green said. “Having him around, he’s such a good guy to learn from. The thing that’s great about him is that some older players might say, ‘You’ve got to do this.’ He lets you come to him. …

“When we were really struggling last year, he used to say to me, ‘I know we’re not winning, but go in and have good at-bats. Do what you can do.’ And I had a better second half than first.”

The Twins already have found Molitor helpful in the clubhouse as well, even if it has been for only six weeks.

“I’ve really enjoyed being able to talk to him,” said Ron Coomer, whose spring locker was next to Molitor’s. “He’s experienced in everything the game has to offer. And he’s open to questions.

“He’s gone through it all, from contract stuff to a couple of strikes to how to get out of a slump. He’s been pretty free with how to approach the game. That’s really good for a guy like me.”

Picking the Twins

Molitor had his pick over the winter. He had solid offers from the Baltimore Orioles, Cleveland Indians, Milwaukee Brewers and the Toronto Blue Jays, in addition to the Twins.

Paul Molitor goes through infield practice during spring training in March 1996 in Fort Myers, Fla. (Chris Polydoroff / Pioneer Press)

Then, on the day he was to have signed with the Twins, he received a last-minute phone call from the Chicago White Sox asking him not to sign anything until he spoke with them. As if things already weren’t confusing enough.

Molitor signed with the Twins anyway, for nearly $4 million over two years. White Sox manager Terry Bevington approached him before a game this spring, apologizing for his club’s late, somewhat confused entry into the fray.

When Molitor began sorting it all out in November, he sat down with his agent, Ron Simon, and put together a list of criteria. The hometown factor was big, but not the deciding thing.

Molitor agreed to sign with the Twins only after a long conversation with manager Tom Kelly.

“Yes, being a St. Paulite was important, but there were other things, too,” Molitor said. “If you were going to come back strictly because it was your home, I don’t know how long that aspect would warrant a two-year commitment. I think there’s got to be more than that.

“If you didn’t enjoy the guy you were playing for, or the atmosphere in the clubhouse each day … I don’t know what our record is going to be this year, but I know this team is going to compete every day it goes out onto the field.”

As the negotiations wound down, the Molitor family held its breath and prayed.

“Torturous,” was the way Rolland described the time. “It was for us because we knew it was for him. And I don’t think we realized all the factors he considered. We knew the whole Milwaukee thing was a real internal battle for him.”

The Brewers, in fact, were so angry when Molitor declined to return to his first professional home that they ordered his old number, 4, to be given out during spring training. Nobody had worn it since Molitor’s departure in 1992. Suddenly, some non-roster guy named Wes Weger, who had no chance of making the club, wore it this spring.

“I choose to remember Milwaukee in a positive way,” Molitor said. “I had a lot of positive experiences there. It was very enjoyable. I’m not going to let that be tarnished by some people’s interpretation of how things unfolded.

“I feel my reasons were good both for leaving the first time and not choosing to come back a second time.”

In the end, when Milwaukee’s Pat Listach saw that the club was going to make sure No. 4 was worn, he telephoned Molitor and asked if Molitor would have a problem if Listach wore it himself.

“I told him I was flattered,” Molitor said. “The fact that he would call me and somewhat ask permission … that was a classy thing to do.”

In the end, Molitor turned down better financial packages to play with the Twins. He turned down a chance to play for a guaranteed winner. He turned down a couple of very good chances to appear in another World Series.

Which brings up: Has Molitor’s inner fire cooled a few degrees? Is he heading home just to soften up in preparation for retirement?

“Nationally, I think some people might question choosing Minnesota over Baltimore,” Molitor said. “Like, ‘You’re looking at just playing your career out and achieving individual goals.’ It doesn’t really concern me. I think having won in ‘93 may well have been the reason I was able to choose Minnesota. …

“I thought about going to a team to fulfill a role as a hitman, so to speak. But to come in here and be part of trying to rebuild this organization, to make it more competitive toward a championship hunt … whether I’ll be here when those benefits are reached, I can’t say. There are a lot of things. This might not mean I’ll get another (World Series) ring. I hope it does.

“But I’m not going to leave anything in the jar when I walk away from here.”

Chances are, those who would dare question his inner desire with the Twins never saw him as a kid, imitating Harmon Killebrew and Bob Allison in his back yard. Or listening to the Twins on the radio and envisioning himself in a uniform. Or dragging his father outside after dinner each night to play catch.

“Earl Battey, Mudcat Grant, Camilo Pascual … I remember a lot of things,” Molitor said.

“Cesar Tovar playing every position, getting hit in the shoulder every other day. Harmon pulling his hamstring in the All-Star Game.

“I have a lot of memories.”

He finally slipped on a Twins uniform for the first time in early February, when he played in the University of Minnesota alumni game.

And after 19 seasons in the majors, two World Series, six All-Star Games and nearly 3,000 hits,you know what he did before the game started when he got dressed?

He sneaked into the clubhouse bathroom and peeked in the mirror.

“Had to check out those pinstripes,” he said.

Memories of mom

Of course, one seat will be empty when Molitor pulls on the Twins uniform for real Monday, one branch missing.

Paul Molitor’s mother, Kathie Molitor, seen here in July 1985, was her son’s biggest fan. She died in 1988.(Mark Morson / Pioneer Press)

In 1988, Kathie Molitor, Paul’s mother, died unexpectedly at age 59 from an asthma attack. Paul was her first son, and Kathie provided the encouragement and the support. Paul provided the joy.

“We had a lot of fun in those days, with all the ballgames and families,” Richard Molitor said. “Even when he was a kid, bouncing the baseball off the side of the house.

“Fortunately, we had a brick house.”

That first trip to Metropolitan Stadium as a Brewer? Nobody was more proud than Kathie.

It was a special time.

“That’s the only thing that’s been a little melancholy,” Rolland said. “I remember during Paul’s college career, we’d go to Siebert Field, and Bobby Allison would come and watch Paul. My mom, since I was a little girl, had a crush on (Allison) …

“She saw Paul through from early on.”

Molitor, a faraway look in his eyes, nodded.

“I don’t dwell on that, but naturally, she played a special role — not only as your mom, but as a special lady who gave so much,” he said. “To raise eight kids and still find time to be a big fan of mine.

“Naturally, I’d love to have her have the opportunity to see me play for the Twins. Time helps those things.

“We all miss her. It was sad to lose her at a young age. She was very supportive, and she had a lot of baseball knowledge.”

She will be there in spirit, of course, and there will be times this summer when the Molitors will be gathered in the Metrodome, or at dinner or in the back yard, and a knowing glance will be exchanged.

Certainly, this will be a summer suitable for framing. Ballgames. Family. Friends. Local phone calls and last-minute plans and helping with the kids. Who says you can’t go home again?

Roots.

It can be such a big word.

“It’s going to be like old times,” Richard Molitor said. “We can hop in the car and go to the ballpark and see Paul play.”

Now, maybe Dave can get out for a round of golf with his brother one summer’s afternoon. On an off day, of course. And as for that extra spaghetti on Carol’s stove, well, there will be plenty of home stands.

“Paul is a sentimental person,” Roach said. “He believes in God. And he really believes this is his destiny.”

They’ve already had one family celebration — the night before Molitor signed with the Twins, they went to dinner at J.D. Hoyt’s and toasted Paul’s homecoming.

Starting Monday, all of Minnesota can join in the toast.

“I think Midwestern people, not to make too much of a generalization, you don’t ever want to get too far from your roots,” Molitor said. “I realize the importance of growing up in St. Paul, the school system, the Parks and Recreation Department, coaches, family. All of those things haven’t gotten lost over the years. I’ve tried to maintain relationships.

“I’m glad I did now, because it’s going to make this year all that much sweeter. No matter what happens on the field, I think it’s going to be something that will be very memorable.”

Get the book

“From St. Paul to the Hall”: the Pioneer Press chronicled the careers of Dave Winfield, Paul Molitor, Jack Morris and Joe Mauer, and we’ve compiled the best of our coverage into a new hardcover book that celebrates the legendary baseball legacy of Minnesota’s capital city. Order your copy of “From St. Paul to the Hall.”

Related Articles

St. Paul vs. Mobile, Alabama — which is the capital for Hall of Famers?

John Shipley: Inside the decision to let Joe Mauer catch one last time