We checked in with Hollywood writers a year after the strike. They’re not OK

LOS ANGELES — For 14 straight years, Ted Sullivan was consistently paid to pen stories for the screen. The Hollywood-based, 53-year-old TV writer and producer’s résumé boasts credits on hit shows such as “Riverdale” and “Star Trek: Discovery.”

Now, he spends seven to eight hours a day writing without pay, preparing for the unforeseeable moment that Hollywood studios start greenlighting projects and hiring writers again. He misses the picket lines of the WGA strike, which, to him, were the next best thing to working in a writers’ room, surrounded and supported by colleagues.

He hasn’t worked in a real writers’ room since the strike began.

“I feel like I’m in the worst ‘Twilight Zone’ ever,” Sullivan said, “where I wake up and I’m now 20 years old again writing spec scripts for free in my apartment.”

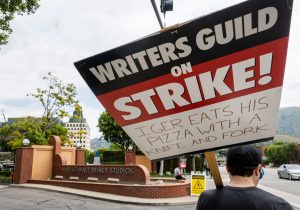

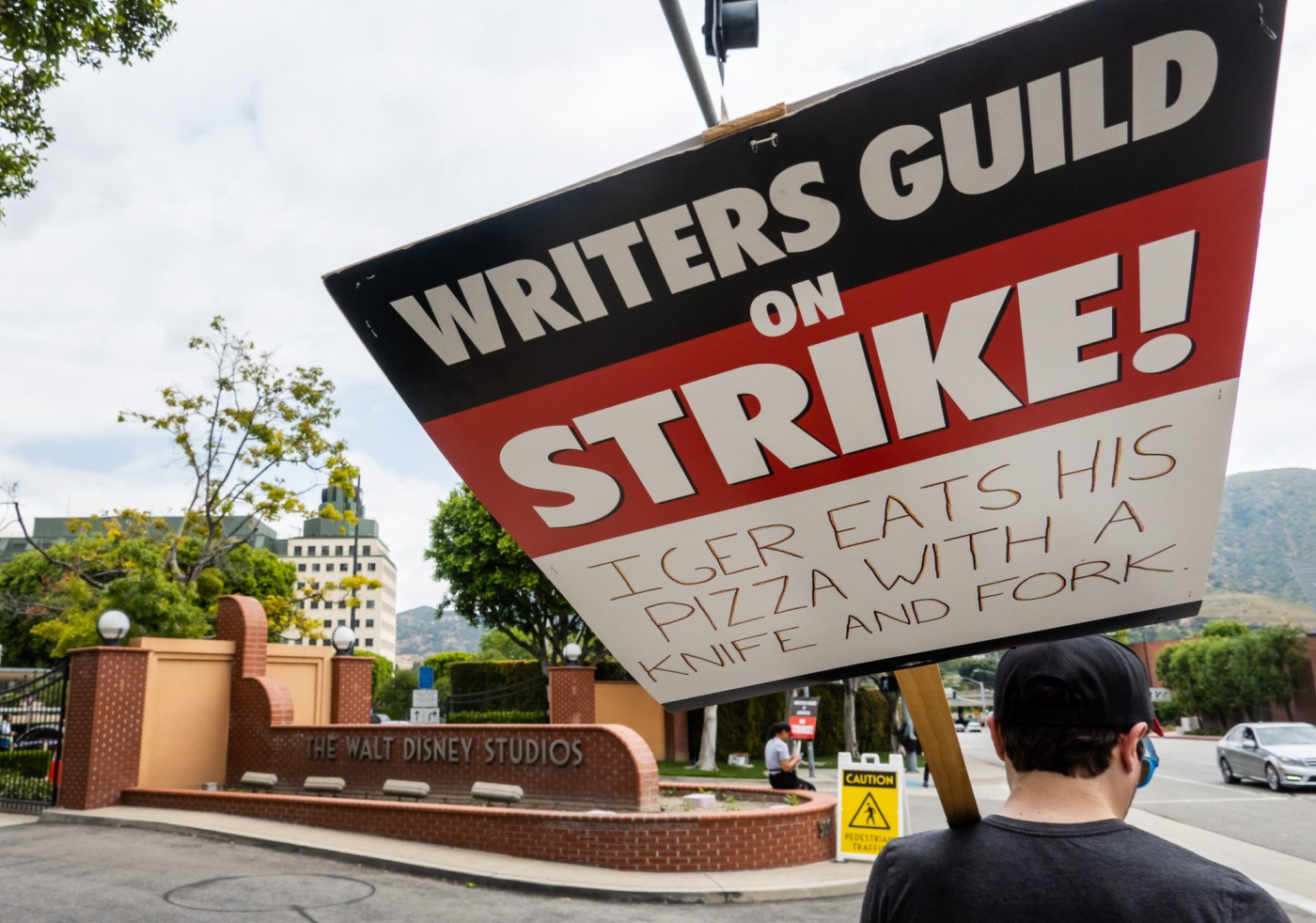

A year after Writers Guild of America members walked out in pursuit of higher wages, enhanced streaming residuals and limitations on the use of artificial intelligence, The Times checked in with multiple writers of varying experience levels spanning film and TV.

Some declined to be named to avoid risking future employment. All said that either they or their colleagues have struggled to find work for at least 12 months amid a contraction that has led to unstable production and employment levels across the entertainment industry.

The so-called peak TV era that enabled 599 original scripted series to land in a single year is over, likely never to return.

Film, TV, commercial and other production activity in the first quarter of 2024 was 20.5% lower than the five-year average, according to FilmLA, a nonprofit organization that tracks on-location production in the Greater Los Angeles area.

Globally, film and TV production lagged by about 7% in the first quarter of 2024 compared to the same period in 2023, per tracking company ProdPro.

“We’re not seeing this V-shaped recovery in writer employment,” said Patrick Adler, principal at Westwood Economics and Planning Associates. “If you squint, maybe it’s a slight upward bounce. But … it’s not perceptible in the data that there’s been some switch flipped on in the industry.”

The slowdown did not originate with the work stoppages of 2023. Writers and other entertainment workers began noticing a decline in employment opportunities long before the writers’ and actors’ strikes began.

Following the so-called streaming wars — when companies spent exorbitant amounts of money on direct-to-digital content to compete with Netflix — studios have dramatically slowed their pace.

Television networks have been purchasing far fewer shows, “and only from big names,” said Jess Meyer, a writer known for “The Flight Attendant.”

“You need cachet to even sell.”

The studios’ cost-cutting strategy has left writers in a pinch.

“As a viewer, what is there to watch? How can they make nothing?” Meyer said. “Even producers are saying, ‘Let’s wait until the right moment.’ I don’t know what that means.”

Some have speculated that entertainment companies are determined to lie low until they can recoup the money lost in the streaming frenzy. A studio executive who was not authorized to comment disputed that idea.

“I’ve never heard of anyone saying, … ‘We’re intentionally going to sell less,’” the executive said.

Another studio source who was not authorized to comment said the pullback was necessary because the TV production boom was “simply unsustainable.”

“Factors such as rising production costs, a lack of competitive film and television tax credits here in California, and shrinking advertising revenue certainly play into that, but this contraction is a return to normal more than anything else,” the person said.

The shrinking business has been particularly challenging for writers from underrepresented groups. Aiko Little, an early-career writer who serves as vice chair of the WGA’s Native American and Indigenous writers committee, said that they began to notice a dip in employment opportunities near the end of 2022.

From left, Lane Factor as Cheese, Paulina Alexis as Willie Jack, D’Pharaoh Woon-A-Tai as Bear, Devery Jacobs as Elora Danan in “Reservation Dogs,” a rare TV series centering on Indigenous characters. (Shane Brown/FX/TNS)

During the peak TV era, writers in Little’s circles encountered more openings than usual thanks to projects centered on Indigenous characters, such as FX’s “Reservation Dogs” and Peacock’s “Rutherford Falls.”

More recently, Little observed, it’s been difficult for Native American and Indigenous writers to secure jobs beyond the occasional documentary or revisionist western.

“I’m used to the uncertainty,” Little said. “But how do you explain to your community that the possible is looking more impossible?”

Some seasoned writers remember the start of the streaming revolution as a boon for writers. One screenwriter, who spoke anonymously to protect job opportunities, compared the advent of streaming to the arrival of Uber, when it seemed like “anyone with a car” could make a decent living on their own schedule.

Eventually, that started to change. Writing staffs and paychecks began to shrink. Hiring processes became more demanding and expensive, with companies requiring job candidates to participate in “pitch competitions” and prepare “elaborate PowerPoint presentations” hawking their ideas, the screenwriter said.

“It’s not enough to go in with a pitch,” said Chuck Rose, a 20-year writing veteran with several TV and film projects now in development as well as a series on Amazon. “It has to be based on [intellectual property] … and networks want them with an actor attached.”

Even when the streaming business appeared to be booming, industry leaders had been waiting for the other shoe to drop, said one studio executive who was not authorized to comment.

“I think when the pandemic started, the fear became more real,” the executive added. “I don’t think it’s a surprise to anyone who follows the business.”

The TV and streaming industry’s consolidation means writers will continue to struggle with fewer buyers. A major setback for writers was Nexstar Media Group’s 2022 takeover of the CW Network — previously considered a haven for up-and-coming storytellers seeking steady work and upward mobility.

Writers told The Times that since the CW changed hands from Paramount Global and Warner Bros.’ Discovery, one of their last reliable sources of employment has all but disappeared. Under Nexstar, the CW has been moving away from scripted, young-adult-facing dramas toward live sports and other programming targeting its parent company’s evening news-watching audience.

“Mentors had ushered many of us toward going that route,” Little said. “So when the blow of the CW happened, I think many of us were left at a bit of an impasse. … It was a challenge for the mentors as well. I think a lot of them felt, possibly, a little helpless.”

The CW sale is one of many corporate shakeups in recent years. Walt Disney Co.’s acquisition of 21st Century Fox, followed by Warner Bros.’ merger with Discovery, also have taken a toll on employment — with the possible sale of yet another major studio, Paramount, still looming.

The “Core Four” of “Riverdale” returned in Season 6. They are, from left, Betty (played by Lili Reinhart), Veronica (Camila Mendes), Archie (KJ Apa) and Jughead (Cole Sprouse). The CW was once considered a haven for early-career writers seeking steady work and upward mobility.(Courtesy The CW/TNS)

Post-merger, Warner Bros. Discovery has stood out for shelving film and TV projects that, in some cases, have already been completed, in favor of tax breaks and other savings.

“That’s work that people have spent a lot of time on that … they don’t get to put on their résumé anymore,” said Madison Bateman, an animation writer and story editor known for “DuckTales” and “The Ghost and Molly McGee.”

CGI cartoon renderings of the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote in a dim dungeon.

According to Bateman, many animated productions have switched from hiring staff writers to freelancers, who make less and sometimes have to wait several months for paychecks.

What was once a career that Bateman’s parents could “brag to their friends about” has devolved into “the exact thing that they were worried about and warned … about having a backup plan for.”

“I’m flipping furniture now,” she said. “A friend is learning to groom dogs. We’re really having to scrounge for work.”

While attention has primarily focused on the challenges in TV, film writers have been feeling the squeeze as well.

Veteran feature writer Cameron Ali Fay began to notice a downturn at the beginning of 2022, when Netflix revealed in a bombshell earnings report that it had lost 200,000 subscribers, tanking the streaming giant’s stock.

“That caused a lot of shockwaves,” Fay said. “I think every other streaming service was looking at that and thinking, ‘Oh my God, we’ve gotta tighten our belts.’”

Prior to what Fay called “the Netflix ripple effect,” feature writers could count on streamers to invest in original screenplays, even as the theatrical release calendar was decimated by the COVID-19 pandemic and ultra-fixated on established intellectual property.

Most feature writers — who aren’t fortunate enough to be operating in the big-budget IP space — have since been left to compete for dwindling streaming deals, Fay said.

“It’s a really difficult business,” Fay added, “and I’ve only seen it get more difficult for the majority of artists in the past 17 years.”

The WGA strike culminated in a historic deal in September that raised writers’ wages, established AI protections and created minimum staffing requirements.

Those gains have “started to reverse some of the damage,” one writer said. But until the rest of the industry bounces back, the wounds could take some time to fully heal. “Survive to ’25” is a sentiment that writers have begun to internalize.

“I really, really worry about these young writers, and … sometimes I feel guilt — like I should be talking them into doing something else with their lives,” Sullivan said. “But nothing would have stopped me. And I know that nothing will stop them.”

_____

©2024 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.