How Expanded Obamacare Made Premiums Spiral, Americans Dependent

By Lawrence Wilson and Sylvia Xu

Congress responded to the COVID-19 pandemic by passing the American Rescue Plan Act in early 2021. This $1.9 trillion spending bill was intended to provide relief and spark an economic recovery.

Among other provisions, the law expanded the availability of government-subsidized health care through the Obamacare Marketplace to help low- to middle-income people maintain health coverage until the economy normalized.

The measure brought millions of middle-class Americans into Obamacare, but had the unintended consequence of making many of them dependent on government aid.

The law also introduced temporary, enhanced subsidies, which raised Obamacare premiums, some observers say.

Though the enhanced subsidies expired on Dec. 31, 2025, Congress continues to debate their possible reinstatement.

Expanded Enrollment

Obamacare was created for people caught in the gap between Medicaid coverage and employer-sponsored health insurance.

The program provides income-based premium tax credits, which are subsidies paid directly to insurance companies, for people whose incomes are on the poverty line and up to four times above the poverty line between 100 percent and 400 percent of the federal poverty level.

People earning less than—or in some states, up to 138 percent of—the poverty level are eligible for Medicaid. Obamacare offers help for people earning up to four times that amount, up to $62,600 per year or $106,600 for a family of three, based on the current federal poverty level.

During the pandemic, Congress created subsidies that had no income cap. These enhanced subsidies also lowered enrollees’ affordability cap—the maximum amount a customer would pay out of pocket for a monthly premium.

Under the enhanced subsidies, introduced in 2021, no enrollee would spend more than 8.5 percent of their monthly income on premiums. Some would pay no more than 6 percent, others 4 percent or 2 percent, and some would pay nothing.

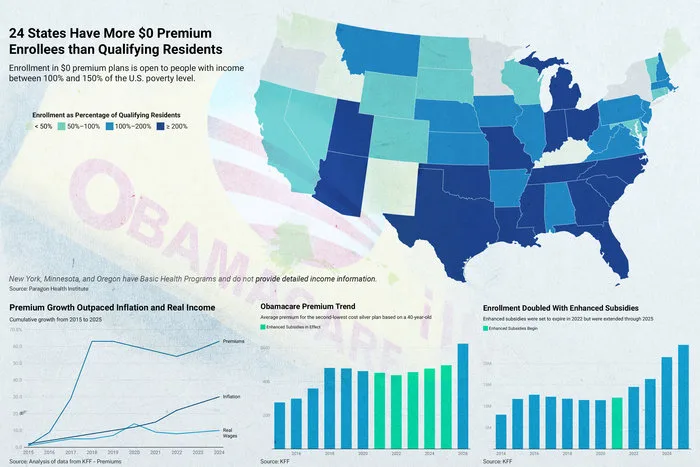

Enrollment boomed, jumping from 11.4 million to 14.5 million in two years. By 2025, enrollment had doubled from its pre-pandemic level, topping 24 million, according to data from health research organization KFF.

The enhanced subsidies were set to expire in 2022, allowing just enough time to get people back to work.

But when the pandemic ended, the enhanced subsidies remained.

House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.) and fellow Democrats hold a news conference on the East Front Steps of the U.S. Capitol on Dec. 18, 2025. Jeffries said on Jan. 5 that House Democrats are seeking to extend the Affordable Care Act tax credits, which expired on Dec. 31, 2025. Heather Diehl/Getty Images

Premiums Increased, Wages Didn’t

Health insurance premiums increased dramatically during Obamacare’s first five years. The average individual premium for a 40-year-old went up at least 75 percent, according to data reported by KFF.

Prices soared in commercial markets, too, where the cost of individual premiums rose about 120 percent from 2013 to 2019, according to The Heritage Foundation.

Obamacare prices leveled out before the pandemic hit and from 2020 to 2022, which includes the first two years of enhanced subsidies, prices dropped 5 percent, according to data reported by KFF.

But in 2022, the year the subsidies were set to end, inflation was on the rise, peaking at more than 9 percent by midyear, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Economists broadly agree that this was an unintended consequence of American Rescue Plan spending. The rising prices were “the product of easy fiscal and monetary policies, excess savings accumulated during the pandemic, and the reopening of locked-down economies,” Ben Bernanke, former chairman of the Federal Reserve, wrote in a co-authored assessment for Brookings.

Congress responded by spending even more money. The Inflation Reduction Act, passed in August 2022, would pump another $1.2 trillion into the economy within a decade, the Cato Institute estimated. That included a three-year extension of the enhanced subsidies.

(L–R) Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), Sen. Mike Crapo (R-Idaho), and Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio) speak at a press conference at the U.S. Capitol on Aug. 3, 2022. While most Republicans opposed extending the enhanced Obamacare subsidies, some supported a second short-term extension of one to three years. Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

Obamacare premiums shot back up, according to data reported by KFF, rising more than 13 percent in three years.

Economic and policy researcher Cynthia Cox for KFF pointed to a number of factors driving the recent rise in premiums, including increased hospital costs, the rising popularity of expensive new drugs such as Ozempic, and the use of tariffs.

Many observers also cite the enhanced subsidies themselves as a driver of the problem they were created to address.

“The Affordable Care Act subsidy structure is itself inflationary—driving up health care prices and total premiums,” said Mark Howell and Brian Blase of the think tank Paragon Health Institute. “As Congress considers the future of the COVID Credits . . . it must confront the reality that the [Affordable Care Act] made coverage far less affordable.”

That reality was largely hidden from many who received the enhanced subsidies because their out-of-pocket premium payments were capped based on income. Price hikes above that cap were paid by taxpayers, which meant the enhanced subsidies were now even more important for people with modest incomes.

Meanwhile, the real wages of American workers were not keeping pace with the price of consumer goods, let alone the skyrocketing cost of health insurance.

Around that time, Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) commented on the value of the enhanced subsidies to members of his congressional district. “Without the Inflation Reduction Act, the average premium for these individuals would have increased by 76 percent, to $1,430, in 2023,” he said in a statement.

By 2025, the year the enhanced subsidies were again scheduled to expire, Obamacare premiums were at their highest point ever. Health insurers realized that, without the additional subsidies, healthier enrollees would drop their coverage in 2026, leaving a smaller, more expensive pool of people to insure, according to the Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker.

Insurers responded with premium increases ranging from 10 percent to 59 percent, Peterson-KFF found, with the median being 18 percent.

Congressional Democrats argued that the enhanced subsidies had become essential and moved to make them permanent. Some Republicans agreed that a second extension of one to three years was needed.

After five years of premium increases largely paid for by federal taxpayers, both the insurers and the insured appear to have become dependent on the enhanced subsidies.

An Obamacare sign sits in front of an insurance agency in Miami on Nov. 12, 2025. Enrollment in Obamacare surged under the enhanced subsidies—doubling from its pre-pandemic level to more than 24 million by 2025, according to health policy group KFF. Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Increased Fraud

Most Republicans opposed extending the enhanced subsidies. Before spending more money on rising premiums, they said another problem hidden in the system needs to be fixed first—fraud.

There has been no dispute among lawmakers that the enhanced subsidies have been a boon to consumers.

The average Obamacare premium for 2025 was $619 per month, of which subsidies covered more than $500. More than 10 million enrollees, 46 percent of those receiving aid, paid $10 or less per month out of pocket for premiums.

About 8 million paid $0, according to Brookings.

That’s exactly the problem, according to some analysts, because the possibility of enrolling large numbers of people who would never receive a bill created a ripe opportunity for fraud.

Many people were enrolled in the program without their knowledge by unscrupulous insurance brokers, Blase alleges, prompting the federal government to send a commission check to them—and premium payments to an insurance company.

These phantom enrollees are detected in part by their lack of activity once enrolled, Blase said.

“In 2024, nearly 12 million enrollees did not use their plan a single time—up from fewer than 4 million in 2021,” Blase told the House Judiciary Committee on Dec. 10.

Overall, 35 percent of all exchange enrollees never used their plan, and 40 percent of fully subsidized enrollees did not have a single claim, which Blase said is double the rate in both the commercial market and pre-pandemic Obamacare.

America’s Health Insurance Providers, the trade association for health insurance companies, disputed that claim.

“A ‘no-claims’ year is evidence that a consumer stayed healthy or only had a few months of coverage—not that taxpayer money was misdirected or that their policy was illegitimate,” the group said in an Aug. 18 statement.

Yet in December 2025, the Government Accountability Office provided evidence of enrollment fraud in Obamacare that suggests fake accounts are being created.

Pages from the U.S. Affordable Care Act health insurance website healthcare.gov are seen on a computer screen in New York City on Aug. 19, 2025. Patrick Sison/File/AP Photo

Investigators were able to enroll 20 nonexistent identities in Obamacare in 2024 by using Social Security numbers that had never been issued to any person and other easily created counterfeit documents.

Of the 20 false enrollments, 18 were still active in September 2025, costing taxpayers more than $10,000 per month.

Investigators also found 26,000 accounts that received subsidies in 2023 based on Social Security numbers that matched records in the Social Security Administration’s death file.

More than 7,000 Social Security numbers belonged to people who were reported dead before enrolling in Obamacare, and 19,000 Social Security numbers matched death data by number but not name and address, indicating that false identities may have been created for enrollment.

Taxpayers paid more than $94 million in subsidies for one year based on those numbers.

Another indication of fraud is the number of states where enrollment in Obamacare plans with a $0 premium is unreasonably high compared to the number with a qualifying income.

Twenty-four states have more Obamacare enrollees claiming incomes between 100 percent and 150 percent of the federal poverty level than there are people living in the state with that income, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

The problem appears worse in states that have not adopted expanded Medicaid, which would have increased Medicaid eligibility to 138 percent of the federal poverty level.

Obamacare customers are automatically re-enrolled each year, so a fictitious account would continue to generate fraudulent commissions and wasteful insurance payments until detected.

Fraudulent enrollment costs up to $20 billion per year, according to Paragon Health Institute.

A Social Security card sits alongside checks from the U.S. Treasury in this photo illustration in Washington on Oct. 14, 2021. The Government Accountability Office found evidence of Obamacare enrollment fraud involving fake accounts created with Social Security numbers of people reported dead before enrollment. Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

Making Health Care Affordable

The enhanced subsidies expired on Dec. 31, 2025.

Congressional Republicans and Democrats continue to agree that the U.S. health care system has become unaffordable and want to address the problem. They differ in approach.

Democrats generally favor government intervention in the system, as in the case of Obamacare, where taxpayers pitch in to cover rising costs.

The Senate in December 2025 rejected a proposal to make the enhanced subsidies permanent.

House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.) said at a press conference on Jan. 5 that his party continues to seek an extension of the subsidies “to protect the health care of tens of millions of … everyday Americans, middle-class Americans and working class Americans.”

Without the subsidies, Jeffries said, some consumers would face cost increases of up to $2,000 or more per month.

Republicans generally favor using the power of government to create marketplace competition. Senate Republicans recently presented a plan to provide dedicated funds directly to consumers, which they could use to shop for health care. That plan, too, was rejected by the Senate.

Sen. John Thune (R-S.D.), the Senate majority leader, addressed the differing philosophies in a Dec. 16, 2025, press conference.

“If [Democrats are] willing to accept changes that actually would put more power and control and resources in the hands of the American people, and less of that in the pockets of the insurance companies, I think there’s a path forward,” he said.

The House passed a three-year extension of the enhanced subsidies on Jan. 8. A bid by Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y) to pass the bill via unanimous consent in the upper chamber failed on Jan. 14.

President Donald Trump has said he would veto any extension of Obamacare subsidies that came to his desk.

Making Health Care Affordable

The enhanced subsidies expired on Dec. 31, 2025.

Congressional Republicans and Democrats continue to agree that the U.S. health care system has become unaffordable and want to address the problem. They differ in approach.

Democrats generally favor government intervention in the system, as in the case of Obamacare, where taxpayers pitch in to cover rising costs.

The Senate in December 2025 rejected a proposal to make the enhanced subsidies permanent.

House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.) said at a press conference on Jan. 5 that his party continues to seek an extension of the subsidies “to protect the health care of tens of millions of … everyday Americans, middle-class Americans and working class Americans.”

Without the subsidies, Jeffries said, some consumers would face cost increases of up to $2,000 or more per month.

Republicans generally favor using the power of government to create marketplace competition. Senate Republicans recently presented a plan to provide dedicated funds directly to consumers, which they could use to shop for health care. That plan, too, was rejected by the Senate.

Sen. John Thune (R-S.D.), the Senate majority leader, addressed the differing philosophies in a Dec. 16, 2025, press conference.

“If Democrats are willing to accept changes that actually would put more power and control and resources in the hands of the American people, and less of that in the pockets of the insurance companies, I think there’s a path forward,” he said.

The House passed a three-year extension of the enhanced subsidies on Jan. 8. A bid by Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y) to pass the bill via unanimous consent in the upper chamber failed on Jan. 14.

President Donald Trump has said he would veto any extension of Obamacare subsidies that came to his desk.