Philipson: Trump’s drug-pricing pressure is working

The White House just announced that AstraZeneca and Pfizer will start charging foreign health systems the same prices for all newly launched treatments as they charge here in America. Bristol-Meyers Squibb and AbbVie have similarly promised to charge the same price in the United Kingdom as in the United States for two soon-to-be-launched treatments.

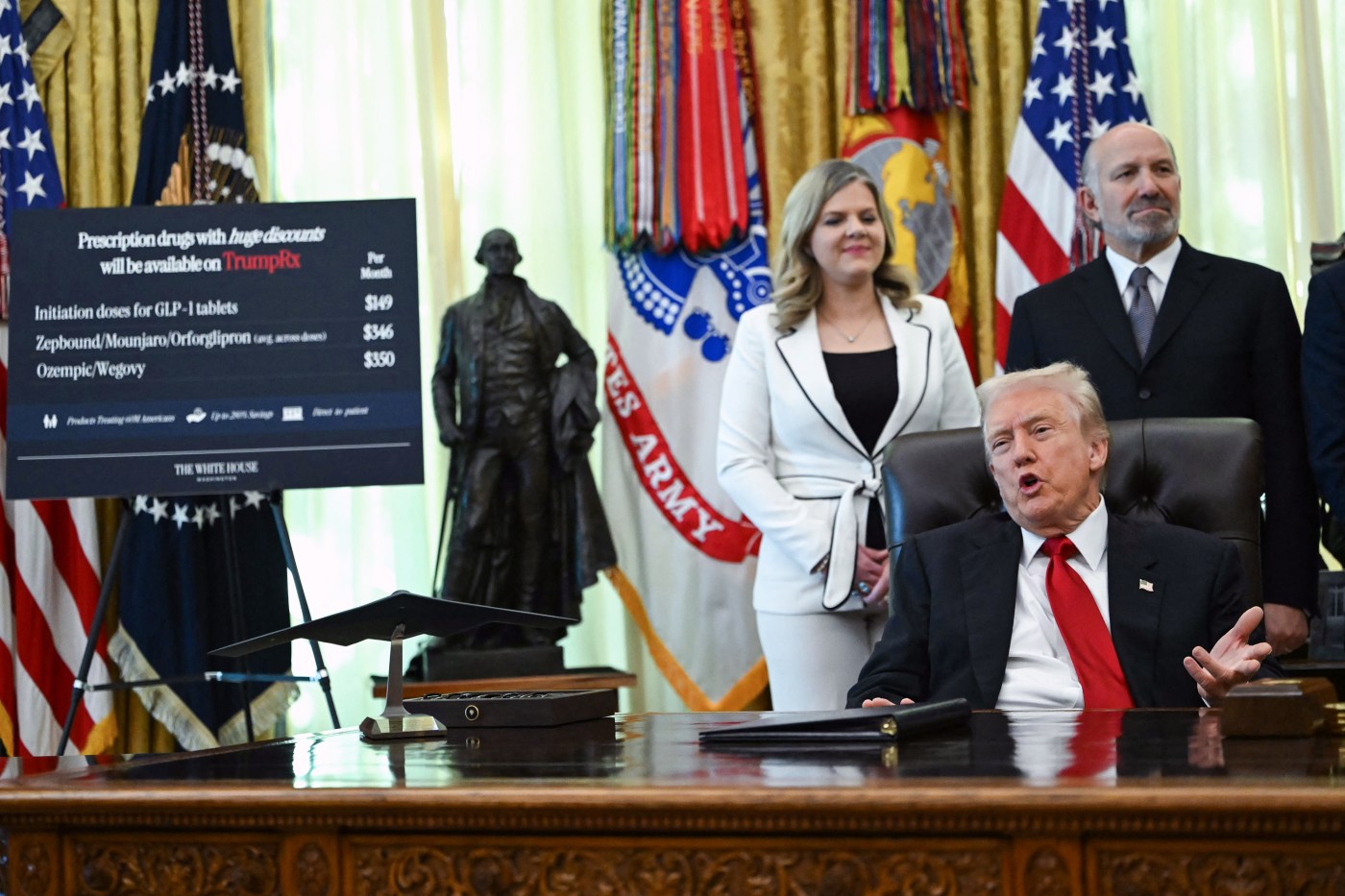

President Donald Trump deserves much of the credit for these pricing decisions. For months, he has been demanding that wealthy foreign governments start paying market prices for medicines, instead of using a variety of direct and indirect price controls to suppress spending on innovative drugs — which forces American patients, employers and taxpayers to shoulder the lion’s share of the global research and development burden.

The recent announcements show that drugmakers finally feel empowered to resist foreign price controls — confident that the administration will have their backs during their upcoming, inevitably contentious pricing battles with European health bureaucrats unaccustomed to paying American prices for American-invented, often American-made medicines.

The White House would be wise to tout wins like these and continue supporting companies in their efforts to charge market prices abroad for newly introduced medicines — all while recognizing that companies have limited flexibility to renegotiate pricing contracts for drugs already on the market.

If administration officials fail to make this distinction — and cap U.S. drug prices at the artificially low levels set overseas — the results could be catastrophic for our collective health and our economy.

In a new paper, my University of Chicago colleagues and I demonstrate that such price controls on existing drugs would reduce biopharmaceutical firms’ U.S. revenues by 49%— leading to a roughly 48% cut in worldwide research and development spending. In turn, that would result in about 500 fewer new drug approvals or indications in a 10-year period.

Despite this immense harm to public health and our economy — the revenue losses alone are equivalent to 0.78% of our gross domestic product, to say nothing of the much greater losses in productivity from increased illness, premature deaths and biotech industry job losses — domestic price controls would not achieve their intended goal of ending foreign free-riding on American innovation.

Individual American companies don’t have the leverage to fix foreign free-riding on their own. But the federal government does — which is why it’s critical for the Trump administration to push other countries to pay their fair share.

He could insist that other developed countries match the 0.8% per-capita share of GDP that the U.S. spends on innovative drugs. That would curb free-riding and inject billions of dollars into the drug development pipeline, benefiting American patients, workers and the economy as a whole.

Tomas J. Philipson is an economist at the University of Chicago and served as a member and acting chairman of the president’s Council of Economic Advisers from 2017 to 2020/Tribune News Service