Bar advocates stand firm against Massachusetts bill that boosts pay by $20 per hour

Bar advocates don’t like the hourly pay rate proposed by the Massachusetts legislature, according to one of the leaders of the work stoppage, who said the “slap in the face” offer has only “strengthened our resolve.”

The proposal to raise wages by $20 per hour over two years was passed Thursday afternoon by both the House and Senate. The legislation was contained in a larger bill, a supplemental budget, that the House passed by a vote of 150-6. The Senate passed it with a voice vote. Gov. Maura Healey has 10 days to sign the bill.

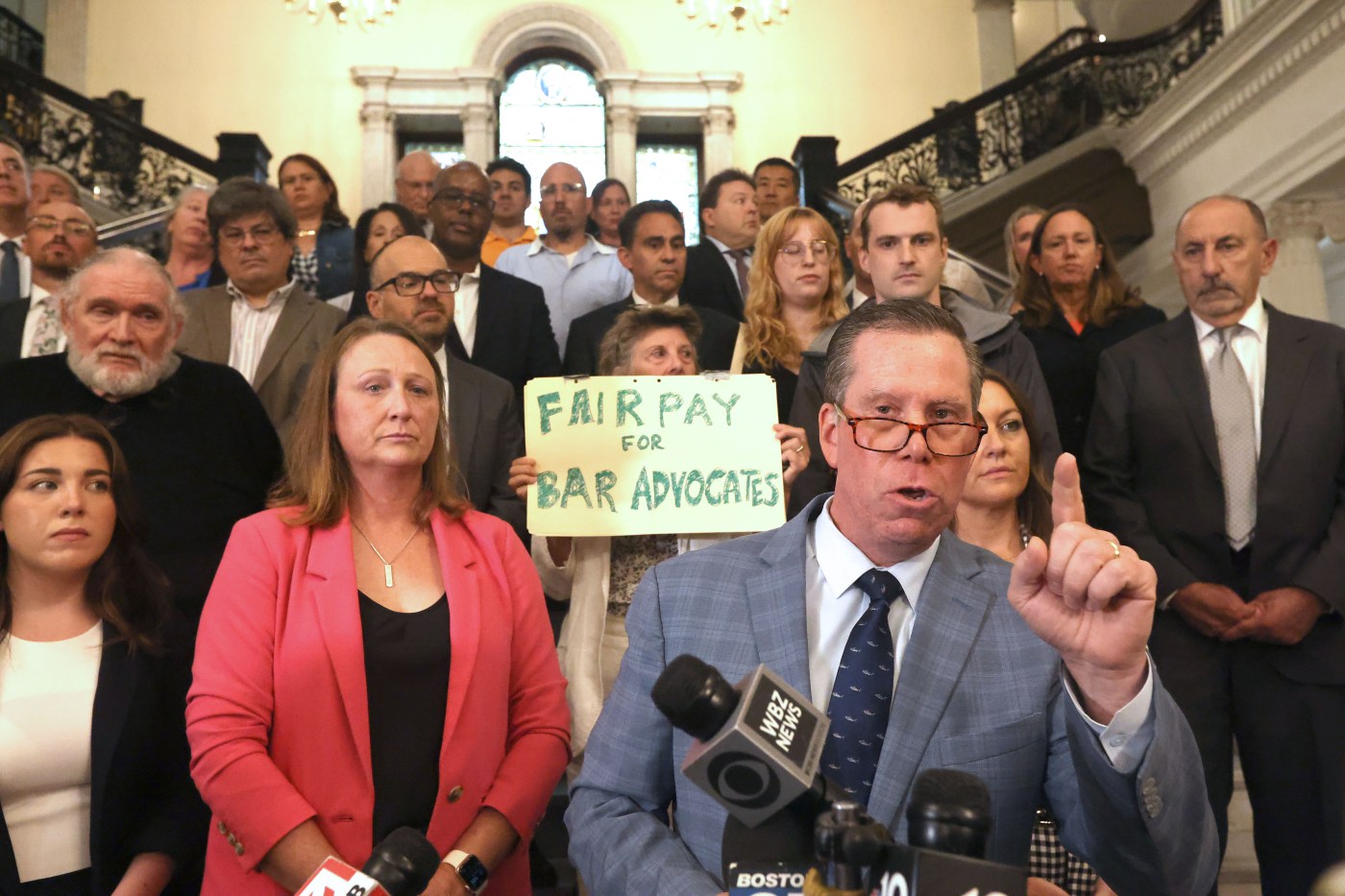

“I say to you today and to the leadership, we’re going nowhere. Your ridiculous proposal that you put forward yesterday has only strengthened our resolve,” attorney Sean Delaney said from the steps of the State House’s Grand Staircase before the vote, with dozens of fellow attorneys behind him.

“You must understand that before you go off on your monthly sojourn in August and disappear from these halls, we are going nowhere,” he continued.

Delaney is one of the primary faces of the movement of bar advocates, who represent some 80% of indigent criminal defendants, or those who cannot afford an attorney, to stop taking on new cases in a push for a raise in their pay.

The situation has led to scores of defendants being released from jail and even having their cases dismissed this month due to a lack of legal representation, which is a constitutional right.

The “work stoppage,” a kind of voluntary strike by the contract workers, began in May and Delaney and other movement leaders say that their requests are falling on deaf ears by legislative leaders.

Those participating in the work stoppage are requesting that pay for those who take cases at the District Court level — which includes Boston Municipal Court — have their pay increase from $65 per hour to $100 per hour, which is still less than surrounding states pay attorneys doing the same work, Delaney said.

Massachusetts legislative leaders countered Wednesday with a proposal that would see a $10 per hour immediate raise and another $10 raise in a year, boosting pay to a total of $85.

Rep. Aaron Michlewitz, a North End Democrat who chairs the House Ways and Means Committee, told reporters Wednesday that he “hopes” the raise will get bar advocates back to work.

Michlewitz also said there had been a “communication breakdown” between the legislature, bar advocates and the Committee for Public Counsel Services, or CPCS — the state agency whose staff attorneys handle the remaining 20% of indigent defendants and that organizes the bar advocate program.

The bar advocates’ cause is further boosted by an open letter supporting them that was signed by 118 retired Massachusetts judges as of 4:30 p.m. Thursday.

The bill is up for a vote on Thursday, but there was no word by 4 p.m. if legislators in either chamber had voted for it. Even if it passes, according to Delaney, that won’t be an end to the strike.

“Personally, I am not taking another case until they do what is right. They know what it is. They have the means and the manner to do it. They refuse to do it,” Delaney continued in his speech from the Grand Staircase.

The situation

The situation is a messy one. Bar advocates in Middlesex and Suffolk county stopped taking on new clients at the district court level in late May and the following month, the Supreme Judicial Court — Massachusetts’ highest court — invoked what is known as the Lavallee Protocol for the two affected counties.

This protocol, named after a 2004 court case amid a similar backlog of criminal defendants, has two prongs to deal with unrepresented criminal defendants.

First, anyone held for longer than a week without legal representation is to be released from detention. Second, anyone without legal representation for 45 days is to have their case dismissed.

Importantly, those cases would be dismissed without prejudice, meaning that prosecutors can file the charges again and the case resumes when the court system resumes normal operation.

Detention hearings happened first, and then came case dismissals. The hearings are held at Boston Municipal Court’s central courthouse and at Lowell District Court.

Differences in opinion

While Delaney’s speech appears to represent a majority opinion by bar advocates, there is evidence that the contract workers are not all in lockstep.

An affidavit filed Tuesday by a CPCS attorney suggested that there has been unfair pressure put on bar advocates who still take on cases.

“There have been instances where bar advocates have confronted lawyers in court on days that they have agreed to take assignments,” attorney Christie Charles of the CPCS Criminal Trial Support Unit wrote in her affidavit. “One lawyer reported that he was angrily confronted by someone who accused him of being a scab and who told him that he would no longer have the support of his fellow bar advocates when he needed advice or a favor.”

Charles continued with an allegation of such conduct: “Despite the fact that they are refusing to take cases, there have been bar advocates attending the Lavallee hearings in BMC Central — ostensibly, in part, to hear the names of lawyers who agreed to take cases …”

When asked about such conduct following his Grand Staircase speech, Delaney said he wasn’t aware of the behavior and strongly condemned it if it was taking place.

Then there are attorneys who are pleased with the offer from the legislature, though the one who spoke with the Herald Thursday works in Bristol County, so was not working in a work stoppage court.

“I understand why some attorneys may want more compensation, especially when considering the pay rates in neighboring states and the recent increase in the cost of living. Based on my situation—as a new attorney and Bristol Bar Advocate practicing out of New Bedford District Court for just over a year—I believe this is a fair compromise for the time being,” attorney Shane Callahan told the Herald in an email interview.

“However, I strongly sympathize with those who believe the raise is still insufficient. Practicing out of New Bedford, I don’t face the same housing or office space costs as attorneys working in Boston, which are significantly higher,” the attorney continued.