Gaskin: Black-Jewish solidarity a union too vital to lose

May is Jewish American Heritage Month, a time to celebrate Jewish achievements and to take stock of the alliances that have strengthened us. No inter-minority partnership in U.S. history has been as productive — or as fragile — as the bond between Black and Jewish Americans. Together we helped dismantle Jim Crow and broaden this nation’s moral horizon. Yet, in recent years, disagreements over policing, the Black Lives Matter movement, and the war in Gaza have reopened old wounds. If we allow those fissures to widen, we will squander a legacy built by giants whose courage we still invoke.

At the dawn of the 20th century, African Americans faced lynch mobs, disenfranchisement, and segregation. Jewish immigrants, many fleeing pogroms in Eastern Europe, met “No Jews Need Apply” signs, college quotas, and restrictive covenants. That double burden of humiliation forged empathy. In 1909, Jewish philanthropists Henry Moskowitz and Lillian Wald joined W. E. B. Du Bois and Mary White Ovington in founding the NAACP; prominent Jewish publisher Joel Spingarn became its longtime board chair and endowed its highest civil-rights award. When you live in the margins together, you recognize one another’s humanity quickly.

During the Great Migration, more than a million Black southerners moved into Northern and Midwestern cities — often into or beside Jewish neighborhoods. On Chicago’s South Side and in Harlem’s Lenox Avenue, Black tenants rented apartments from Jewish landlords and bought clothes on credit from Jewish shopkeepers. Daily commerce knit communities together, yet economic disparity sometimes bred resentment over rents and prices. Still, a powerful idea took root: two historically oppressed peoples could share the same streets and imagine liberation together.

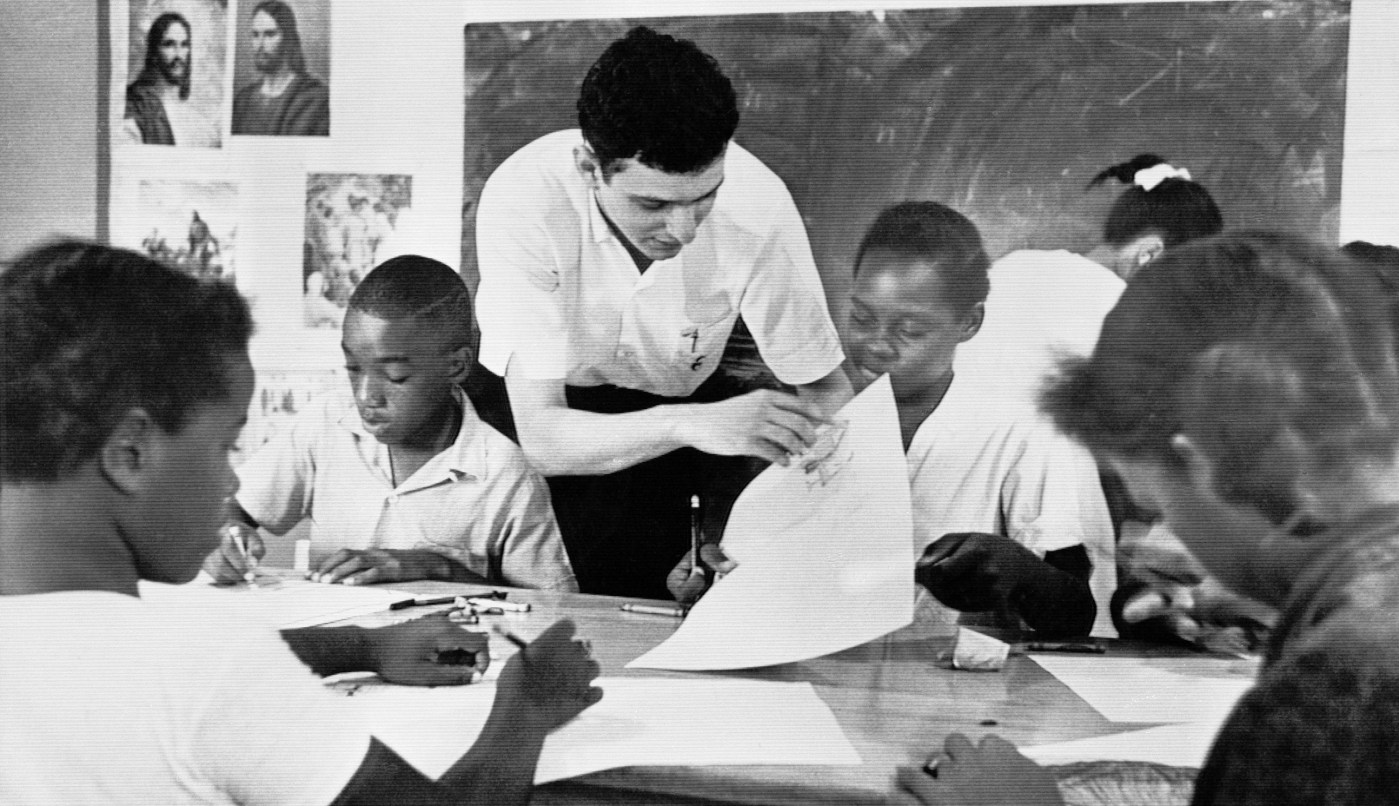

World War II, with its stark lesson about racial hatred, intensified the partnership. Jewish organizations — the Anti-Defamation League, American Jewish Committee, and Jewish labor unions — bankrolled the movement, hired attorneys, and lobbied Congress. Jack Greenberg succeeded Thurgood Marshall at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and co-argued Brown v. Board of Education (1954). Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel marched beside Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma, later saying, “When I marched, my legs were praying.” Their friendship reflected thousands of quieter collaborations: synagogues hosting freedom rallies, rabbis opening pulpits to Black speakers, Jewish donors paying bail for jailed demonstrators.

Women, often unsung, wove the coalition’s moral fabric. Legal scholar and Episcopal priest Pauli Murray brainstormed litigation strategies with Jewish feminists; Ella Baker relied on Jewish volunteers such as Dorothy Zellner to register voters; Rita Schwerner, widow of slain activist Michael Schwerner, toured the country demanding federal protection for Mississippi’s freedom workers. Their cross-racial sisterhood expanded the civil rights imagination beyond male pulpits and courtrooms.

Additionally, Jewish scholars fleeing Nazi Germany and escaping the impending Holocaust found refuge and meaningful roles at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), bringing their expertise to Black students during this critical era and strengthening intellectual bonds between the communities.

No episode captures mid-century solidarity more poignantly than Freedom Summer 1964. When Ku Klux Klan members murdered James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, America saw two Jews and one Black man die together for the right to vote. Their bodies, buried in the same earthen dam, became an altar — proof that the struggle for Black freedom and the Jewish battle against antisemitism were inseparable projects of American redemption.

Solidarity met its first major stress test after 1965. A rising Black nationalism championed by Stokely Carmichael and the Black Panther Party urged self-determination rather than interracial alliances. In Brooklyn’s Ocean Hill-Brownsville district, a Black community school board clashed with mostly Jewish teachers during a 1968 strike over control of public education. Accusations of racism flew both ways; friendships forged in Mississippi unraveled in New York. Meanwhile, urban poverty deepened, and some Black tenants accused Jewish landlords of neglect or profiteering — charges that sparked anger and occasionally violence in places like Chicago’s Lawndale and Newark’s Central Ward.

Foreign policy poured salt in domestic wounds. Many Black leaders, viewing global affairs through an anti-colonial lens, identified with Palestinian aspirations. For American Jews, Israel — barely a generation past the Shoah — remained a non-negotiable homeland. In 1984, presidential candidate Jesse Jackson referred to New York as “Hymie-town,” prompting Jewish outrage. The same year, Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan called Judaism a “gutter religion,” deepening suspicion. Dialogue never stopped, but trust plummeted.

Even in low tide, bridge-builders labored. Black ministers and Jewish rabbis launched the Children of Abraham gatherings. The NAACP and ADL issued joint hate-crime statements in 1997 and again in 2020. In Congress, Black and Jewish representatives co-sponsored bills on voting rights, sentencing reform, and — ultimately — the Emmett Till Anti-lynching Act, signed in 2022.

Ferguson-era protests and the Israel-Hamas war reopened old wounds. Some Jews heard anti-Israel currents in portions of the Black Lives Matter platform, while some Black activists perceived Jewish silence on police brutality; social media amplified every slight. Israel-Palestine sharpened the divide: Hamas’s Oct. 7 massacre re-traumatized a community still marked by the Shoah, even as images of Gazan suffering resonated with Black memories of state violence. Yet bridge-builders refused to surrender. The NAACP and ADL issued joint hate-crime statements (1997, 2020), and artists such as Tiffany Haddish and Jason Alexander launched the Black-Jewish Entertainment Alliance (2021) to fight racism and antisemitism together. At HBCUs, visiting Jewish scholars now teach Holocaust history; in Los Angeles, Black pastors host “Shabbat of Solidarity” services. Most recently, a January 2024 Gaza Cease-fire Clergy Dialogue brought pastors and rabbis together to condemn antisemitism, mourn Palestinian losses, and pledge joint advocacy for Israeli-Palestinian peace—proving that honest acknowledgment of each community’s trauma is the first step toward renewed trust.

Our predecessors prayed with their feet — and sometimes died — because they believed a biblical truth: no one is free until everyone is free. This Jewish American Heritage Month, let us honor that legacy by resisting the temptation to walk away. History shows that when Blacks and Jews stand shoulder to shoulder, America moves forward.

Ed Gaskin is Executive Director of Greater Grove Hall Main Streets and founder of Sunday Celebrations