‘An immense difference:’ Boston schools make moves to keep kids off their phones

As Boston kids and their phones head back to school this year, a wave of new schools are taking a big step to keeps students’ attention off their screens and refocus on learning.

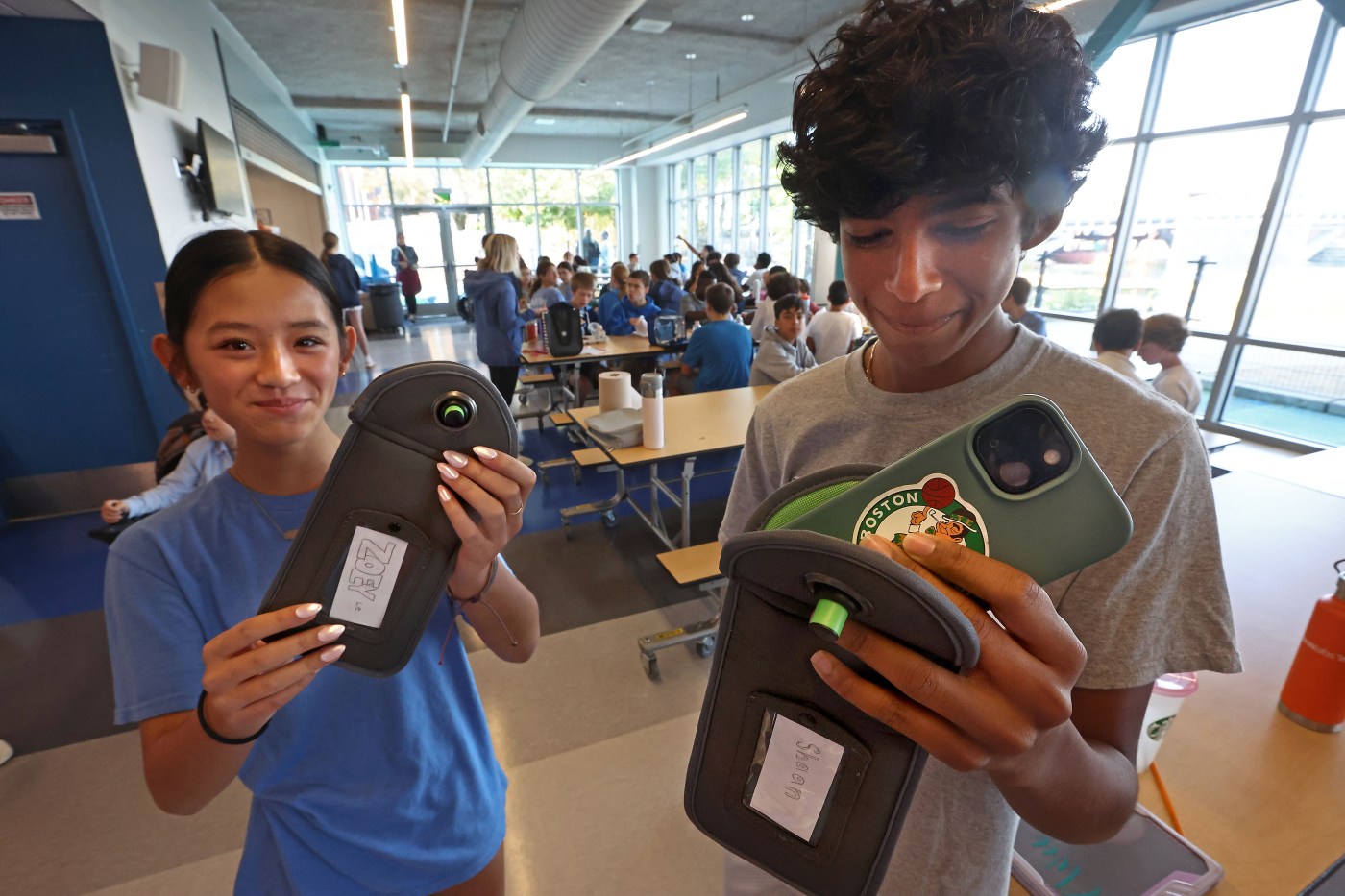

Thirty-one Boston public school have begun or are gearing up to implement systems for students to lock their phones away in “Yondr” pouches throughout the day. Nine elementaries and four high schools are currently using the pouches, BPS Superintendent Mary Skipper said at the start of school.

Students insert their phones — along with any smartwatches or other electronics — in their issued pouch at the start of the school day, check in to magnetically lock the case, and get to unlock the pouch at the end of the school day.

“It’s part of, like, the routine of coming to school,” Zoey, an 8th grader at the Eliot school, said of the pouches in s classroom. “You always have to have your Yondr pouch, and if you don’t have it, then you usually turn it into the front office. Just part of my routine, I just remember I have to check out my notifications and then turn on (do not disturb), or turn it off.”

The Eliot School was one of the earliest BPS schools to adopt the Yondr pouches, having used them since returning from COVID.

Ahead of the school year, BPS awarded a nearly $850,000 contract to Yondr for a three-year “cell phone reduction program” between 2024 and 2027. Under the program, schools with grades 5 through 12 are able to optionally engage in a community outreach process and opt in to participate in the Yondr program, leading to a slew of new schools following in the Eliot’s footsteps in the coming year.

The district’s move to reduce cell phone usage follows a state and nation-wide push to address the use of cell phones in schools, as spiking usage, social media habits and mental health concerns infiltrate classrooms. Massachusetts education officials addressed incentives for cell phone restriction policies and other steps at the end of the 2022-23 school year.

Rolling out the program, Skipper cited “national trend data and studies, as well as our own experiences in schools,” that show the effect of cell phones as a distraction from learning in schools, but said the district is looking to “strike a balanced approach.”

Eliot School Director of Operations and former teacher Huijing Wu said many students returned from COVID lock downs with new “strong attachments” to their phones.

“We’ve had a really big shift in students really being so reliant on their phones,” said Wu. “And we’ve gone from, we’re gonna put the phone in the pouch, and we’re just gonna hold it like it’s our child. They’d walk around and touch the phone, and need to constantly be handling their device. But now kids stick them in their lockers. They’re like, ‘Yep, it just goes away and it’s fine.’”

Now, she added, some students even forget to unlock them at the end of the day.

Several Eliot students said the pouches have changed the way they interact with kids around them and the social pressure they feel.

“You’re not able to look at, especially with AI and ChatGPT, they can’t access that on your phones,” said Eliot 8th grader Can, who doesn’t have a phone. “There’s been more and more use of Tiktok and other social media in schools, like recording videos in the bathrooms and stuff like that. I think it’s been really good with the Yondrs.”

Can said there’s “a lot of peer pressure” to a lot of aspects about having a phone in school.

“If everyone is using the phone and say, like you don’t have one, you kind of feel misplaced,” said Zoey. “Like, ‘Oh, I should be on my phone right now.’ You should actually just be learning.”

Another 8th grader Shaan said students focus more, and are not sneaking looks at their phones in class anymore.

Wu said there were a “few years of growing pains,” for students and parents, but the community has really committed. Some families expressed concern about contacting their kids, she said, but as the school facilitated contact when needed their fears lessened.

“We really pride ourselves on creating a safe environment for for all of our community that’s here and so really thinking about what’s in the best interest for your kids,” said Wu. “We’re here to learn, and we’ve managed years without kids having phones to be able to still contact families.”

Related Articles

Michelle Wu, BPS superintendent join students on bus amid ‘unacceptable’ transportation delays

‘Major update’ to Boston bus routes on the way as on-time woes continue

Advocates warn proposal altering information sharing between BPS schools and police may lead to lawsuits

Boston School Committee signs off on White Stadium redevelopment negotiations over community protest

Boston city councilors press for state intervention after ‘dismal’ BPS bus transportation delays

Skipper said the district anticipates additional schools electing to use the program as the year goes on.

Wu said the policy has made an “immense difference” in kids attention and overall engagement in school, as well as decreasing some bullying behaviors.

“Even something like at recess, when I used to help monitor recess, we’d get clusters of kids around a phone,” said Wu. “We don’t get that. Kids play now. They’re having recess right now, if we were to go look, they’re playing, like kids are supposed to. Not attached to a device.”

Students at the Eliot School use magnetically sealed Yondr pouch to stow their cell phones in during school hours. (Staff Photo By Stuart Cahill/Boston Herald)

BPS Superintendent Mary Skipper (Herald file)