Readers and writers: Three Minnesota writers provide indelible characters

A Finnish Blood Witch. A Hmong-American boy searching for his identity. An angry farmer contributing to generations of abuse. These three novels by Minnesotans offer a wide variety of emotions for readers.

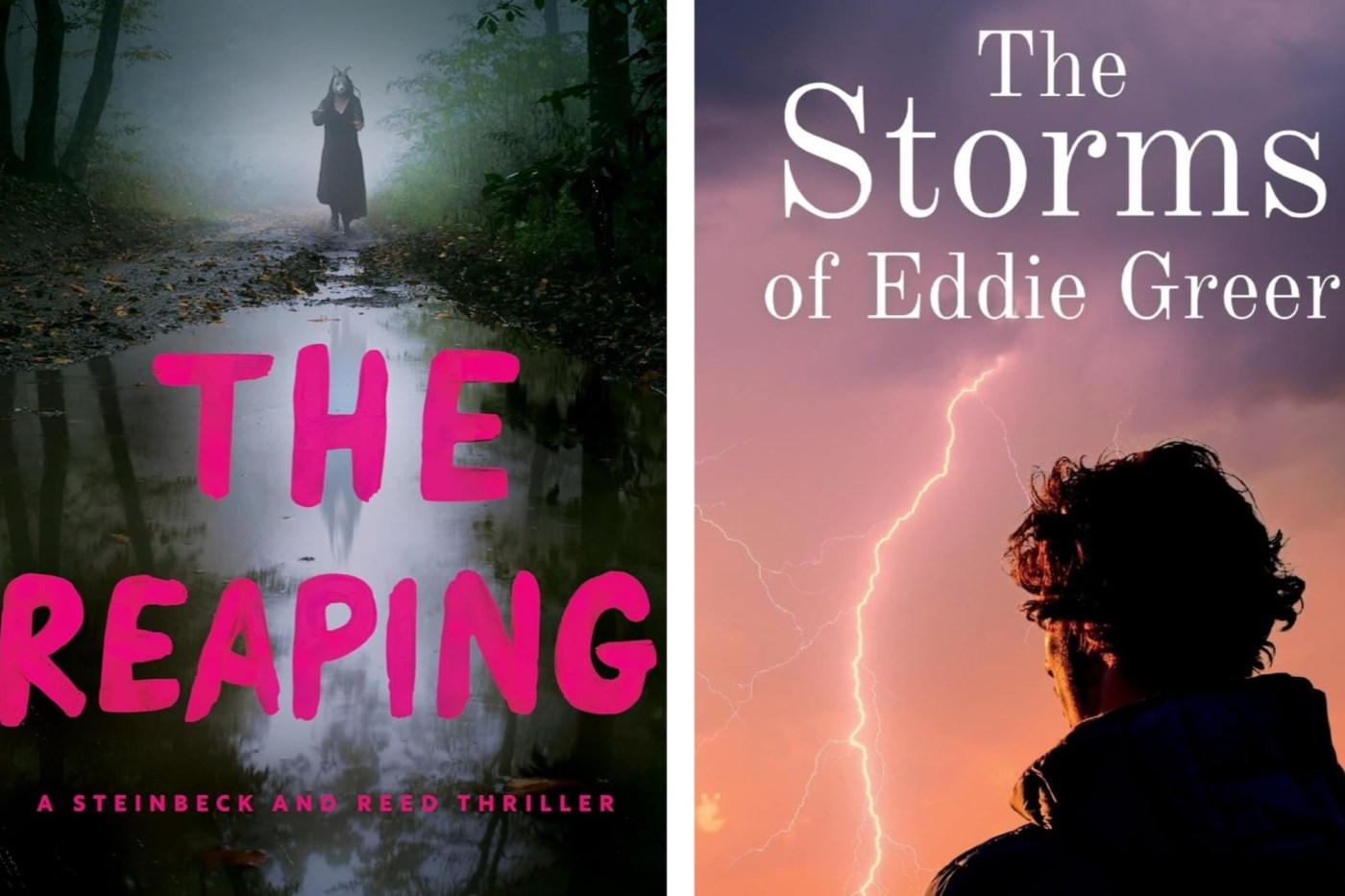

“The Reaping”: by Jess Lourey (Thomas & Mercer, $16.99)

‘Because the veri noita was so powerful, they had to bind her hands and feet in her grave and balance a scythe over her neck so she’d be killed over again if she came back to life.’ His voice dropped. ‘With the veri noita defeated, the disloyal villagers next turned to the original seven families, the veri noita’s truest followers.’ He began breathing heavily. ‘They murdered all their children, every last one of them, in an event that came to be known as the reaping.’ — from “The Reaping”

When we interviewed Jess Lourey last fall about “The Taken Ones,” first in her series featuring Harry Steinbeck and Evangeline Reed, she teased that she would write “a creepy new villain, a Finnish Blood Witch,” in her next novel.

She kept her promise. The Witch is in “The Reaping” and she kills children, or so the kids in the Minnesota town of Alku are told by their pastor. The youngsters know that Alku is family, and you always protect family, no matter what happens.

Harry Steinbeck, a forensic scientist who’s careful and methodical, and rogue Bureau of Criminal Apprehension agent Evangeline Reed, messy, intuitive and willing to skirt the law to get information, are opposites in every way. As Steinbeck muses, they are like “orange juice and toothpaste.” But they have growing respect for one another as they investigate the cold case of a family of five brutally murdered in their home in Alku in 1998. Not only were the mother, father and three children killed, their heads were crushed after death.

The story is told from the viewpoints of Reed, Steinbeck and Rannie, a mentally challenged young man whose mother is one of the town leaders. Rannie will do anything to protect his siblings.

Reed and Steinbeck learn the town was founded by seven families from Finland, some of them doctors, who fled their native country to escape tuberculosis. Because of the way TB acts on the body, their neighbors in the old country thought they were vampires. Alku is now an insular town, not even shown on Minnesota maps, run by descendants of the original Seven. No one else can live in the town near Duluth.

Jess Lourey (Courtesy of the author)

Reed and Steinbeck think the place is weird and creepy as soon as they arrive. The residents have very high foreheads and long necks, and they walk oddly. It’s a town that gives off bad vibes, especially on the outskirts where there is a prison for aged serial killers who need nursing care. An older building, with turrets and old-fashioned architecture, is now a school.

As the partners dig deeper into the town’s history, a prison guard is killed in exactly the same way the family was murdered 25 years earlier. Is this a copycat? Why is there a straw image of the Blood Witch at the door of the church? Why do adults sometimes gather in a forest clearing wearing animal masks?

Throughout the story, Steinbeck is afraid of returning to Duluth, believing he was responsible for the disappearance of his sister years earlier. He’s stunned to learn that his controlling mother, who seemed to hate his missing sister, is now taking foster kids into her lakeside mansion.

What Lourey does so well is blend police procedural with horror vibes that hark back to long-ago beliefs in blood sacrifice.

It’s not a spoiler to reveal that the end assures us there will be a third book in this series. For now you will want to learn more about the Finnish Blood Witch.

Lourey will host a launch party at 4 p.m. Saturday, Sept. 7, at Once Upon a Crime, 604 W. 26th St., Mpls., joined by fellow mystery writers Kristi Belcamino, Wendy Webb and Joshua Moehling. She will sign books at 7 p.m. Wednesday, Sept. 4, at Magers & Quinn, 3038 Hennepin Ave. S., Mpls.; 11 a.m. Thursday, Sept. 5, Comma, a bookstore, 4250 Upton Ave. S., Mpls., with Sarah Stonich, Catriona McPherson, Belcamino and Moehling; 1-4 p.m. Sept. 5, Open Book, Minneapolis-St. Paul Airport, Terminal 1, with Webb, Stonich, McPherson, Moehling and Belcamino, and 2-3:30 p.m. Sept. 21, Hudson Public Library, Hudson, Wis.

Kao Kalia Yang (Courtesy of the author)

“The Diamond Explorer”: by Kao Kalia Yang (Dutton, $17.99)

They had questions. They wanted to know if Hmong is the same as Black. Phong didn’t think so because he, at six, was already beginning to learn about racism and whiteness. Lee was five and less certain. He thought that Hmong was Black because Hmong was not white. I tried to explain that we were Asian and that their father was white. But then they both ended on a singe question: “Can the police kill us or not?’” — from “The Diamond Explorer”

Kao Kalia Yang, one of Minnesota’s most versatile and award-winning authors, has written adult fiction (“The Late Homecomer,” “The Song Poet”) and children’s picture books (“From the Tops of the Trees,” “The Most Beautiful Thing” and others). She’s making her middle-grade debut with “The Diamond Explorer,” abut a boy making his way in the evolving Hmong-American culture.

qIn the first part of the novel Malcolm is seen through the eyes of racist teachers (“You have a very slow kid…”), his parents and siblings. As a little boy he loves living in a house on the prairie cared for by his father, who carefully mows paths in the grass so Malcolm can always find his way back to the house. The book’s title comes from a time he dug among little stones to bring up a piece of red plastic, saying it was a jewel. These scenes are filled with the love Malcolm’s father has for his son.

(Courtesy of Dutton Books for Young Readers)

When Malcolm feels out of place at his school, his parents regretfully agree he should live with his older sister and her husband so he can attend a private school. But then he’s accused of being “too white.” At home he witnesses a shaman’s ceremony to call back the spirit of another sister who returned from college in New York with something missing in her. And Malcolm is worried about his adored older brother, who dropped out of school and is getting into trouble

Malcolm and his cousins have their first experience contemplating death and racism when they learn of the (real-life) death of Philando Castile, an African-American man fatally shot by a police officer in Falcon Heights in 2016.

The book’s second half is a dream journey where Malcolm meets his deceased grandmother and other relatives living in their ancestral homes. They urge him to “go back” but he refuses until he wakes to a shaman’s healing. He returns from his mystical experience with a new love for his people’s stories.

Yang, who was born in a refugee camp in Thailand, grounds every word of this story in her culture, from funeral feasts to times when her people lived in the mountains of Laos.

No matter what character is speaking, the author’s prose shines in the lyrical style we expect from her. The novel, due out Sept. 17, earned early praise from Kirkus Reviews and Publishers Weekly. Kirkus: “Yang has crafted a layered, profoundly moving musing on grief, connection (and lack thereof), and identity..” PW: “(A) richly wrought tale…”

“The Storms of Eddie Greer”: by Mary Perrine (Water’s Edge Publishing, $19.99)

So Eddie gave it all up: the likelihood of a full scholarship and the dream of playing in the majors. In his heart he ended up exactly as the community saw all Greer men: losers, misogynistic, disgruntled farmers, and carbon copies of the head of each generation. And while most of that rang true, Eddie knew the one thing he was not was misogynistic. He hated everyone equally. That was another thing he had learned from the old bastard. — from “The Storms of Eddie Greer”

Eddie Greer inherited his cruelty and alcoholism from males in the family going back generations.

Mary Perrine, former schoolteacher who lives in Cologne, Minn., published this novel last year and is doing appearances this summer. She tells the story of Eddie, an alcoholic and abuser. He knows folks in his town of Holland Crossing expected him to make something of himself. But Eddie had to give up his dreams and take over the farm after his father died. Eddie was a victim of his father’s wrath, physical and verbal abuse that included assault with a baseball bat and shooting the boy’s dog. Some of these passages are difficult to read but they show the results of inherited trauma.

Mary Perrine (Courtesy of the author)

As Eddie stepped into his role as a farmer, he also became a father at age 18. In his immediate family he hates his grandson, his daughter and his wife, Jules, who cannot give him the son he badly wants.

When Eddie’s grandson dies after being struck by lightning in the hayfield because Eddie wouldn’t let the young man stop working, Eddie finally confronts his emotions. Jules, his wife of more than 40 years, is the first Greer woman to stand up to her husband and leave. After that, Eddie takes to sitting in a lawn chair at the edge of the field where his grandson died, contemplating his life. He’s accompanied by his dog, the only creature who seems to love him.

Perrine balances alcoholic rages with the barely-alive love of Eddie for his wife as he struggles to become a new man and break the chain of violence he inherited.

Related Articles

Literary pick for Aug. 18

Kids at the Fair can take a break at the Alphabet Forest

Readers and writers: Plenty of thrills and danger in these Minnesota author’s mysteries

Literary calendar for week of Aug. 18

This Silicon Valley tech worker uses her impostor syndrome as novel inspiration