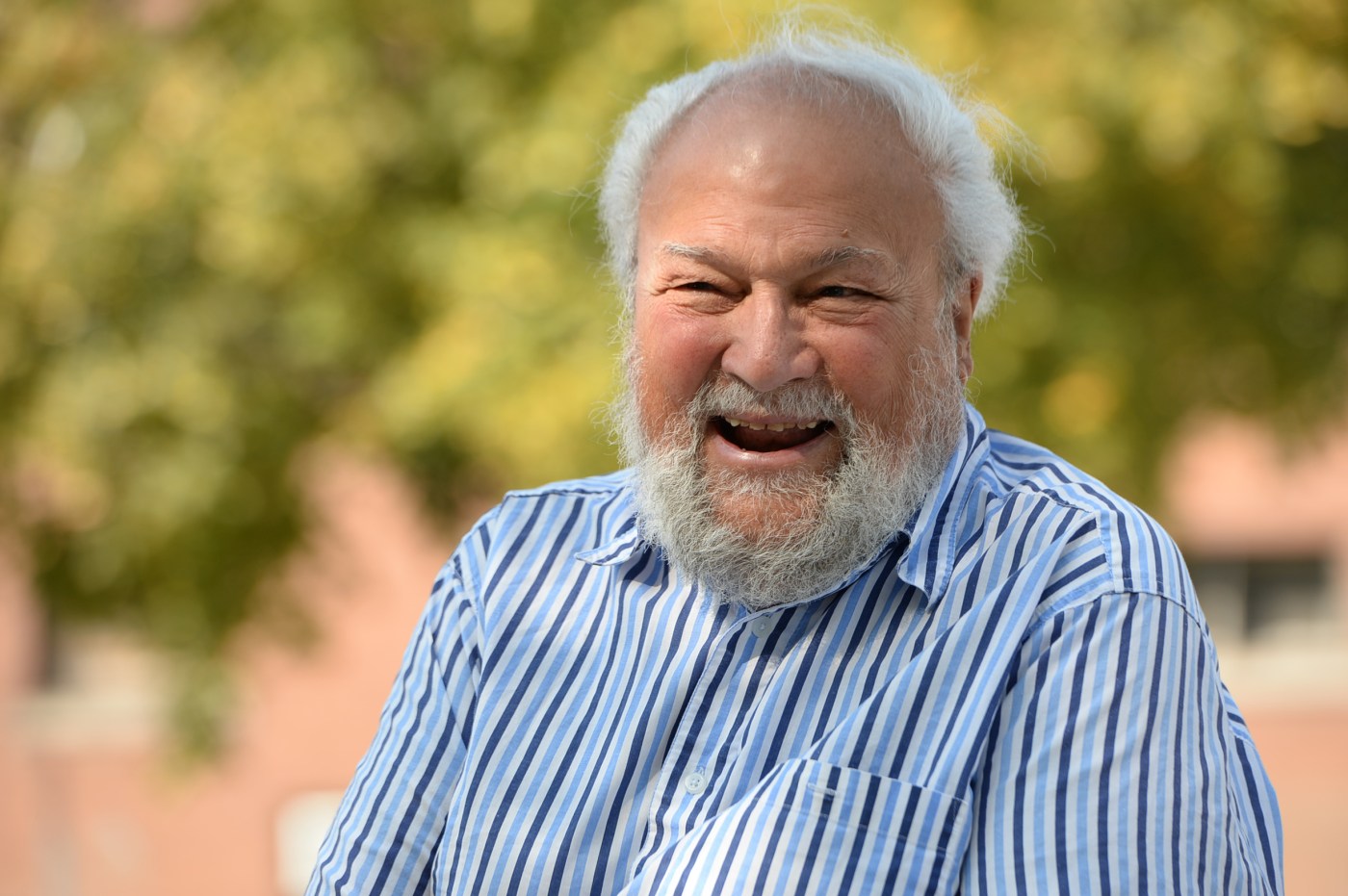

George Latimer, St. Paul’s longest serving mayor, who oversaw rapid change for the city, dies at 89

As the longest serving mayor of St. Paul, George Latimer publicly embraced the social aspects of his job as much as the political ones, becoming so synonymous with the capital city’s downtown institutions that the Central Library by Rice Park was renamed in his honor and the District Energy system he helped launch in the late 1970s dubbed him director emeritus.

Former St. Paul mayor George Latimer, left, and former Minneapolis mayor Don Fraser reminisce during a celebration of the 40th anniversary of Landmark Center in St. Paul on Thursday, Sept. 27, 2018. Forty years ago this month, the Old Federal Courts Building reopened as St. Paul’s Landmark Center after significant community effort for its preservation. (John Autey / Pioneer Press)

Garrulous and jovial, Latimer – a one-time gubernatorial candidate – could disarm a friend or foe with a self-effacing comment, never letting on that his credentials included a degree from an Ivy League law school, a stint as dean of Hamline University Law School and two years in the mid-1990s as a White House adviser on housing policy.

“He was very bright — he went to Columbia Law — but he never gave you that impression that he was better than the average Jane or Joe,” said longtime friend and labor activist Harry Melander. “And if he goofed up, he was the first one to tell you.”

Latimer, who presided over a downtown building boom while serving as one of the capital city’s first official “strong mayors” from 1976 to 1990, died at his longtime Episcopal Homes residence on University Avenue in St. Paul around 12:30 a.m. Sunday. He was 89 years old.

Latimer was preceded by his wife Nancy, who died in September 2006 of ALS, otherwise known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease. The couple had three sons – George Jr., Philip and Thomas More, and two daughters, Faith Tilsen and Kate Courtney.

Presiding in a time of change

Born in June of 1935 in Schenectady, N.Y., and raised by shop owners, Latimer moved to St. Paul in the early 1960s after attending Columbia Law School. He served on the St. Paul School Board from 1970 to 1974 before making his first run for mayor.

Former St. Paul mayor George Latimer, center, shares stories with state Senate secretary Patrick Flahaven, left, and Fred Norton, a Court of Appeals judge, at a reception in St. Paul following Mike McLaughlin’s funeral service on Friday, Aug. 15, 1997. McLaughlin, 73, died Monday at his home on Summit Avenue, and the wake there on Friday helped his family and friends celebrate little pieces in the life of a man who guided local and national Democratic campaigns for four decades. (Scott Goihl / Pioneer Press)

Bill Mahlum, who became Latimer’s law partner in the late 1960s and would go on to help him launch District Energy, recalled how the secret to Latimer’s political success was canvassing.

“If you know George, he has a skill of being very interested in who you are, what you do and who your children are,” said Mahlum, in an August 2022 interview. “He has a great memory, and he cares. He was a remarkable politician, but he was a more remarkable person.”

As mayor, Latimer presided at a time of changing demographics for the capital city, which became a centerpiece of Hmong refugee migration after the U.S. war in Vietnam and “Secret War” in Laos.

It was also a time of national “white flight” to the suburbs, when many middle class families began abandoning urban living, put off in part by rising crime rates across the country and race riots and unrest during the Vietnam era. In the span of three years or so during the 1980s, an estimated 6,000 jobs left the East Side of St. Paul.

Latimer, however, came into his role with unique authority. The city had transitioned under prior Mayor Larry Cohen to a “strong mayor” system, in which rather than hold a single vote on the city council, the executive appointed department directors and oversaw the entirety of city administration. That left the city council to pass city ordinances, approve the city budget and serve as a check and balance on that authority.

“He defined what a strong mayor in St. Paul looks like,” said Chris Coleman, who served as St. Paul mayor from 2006 to 2018 and had known Latimer since childhood.

William McCutcheon, left, and his wife, Marlene, chat with St. Paul Mayor George Latimer shortly after Latimer named McCutcheon the city’s next police chief on Feb. 8, 1980. (Sully Doroshow / Pioneer Press)

In 1981, Latimer gave the eulogy for Coleman’s father, Nicholas David Coleman, a political ally who served as majority leader in the Minnesota Senate for most of the 1970s.

District Energy. Ordway Center

Rather than give up on downtown St. Paul, Latimer doubled down, teaming with Swedish engineer Hans Nyman to create an energy utility to heat and eventually cool downtown at stable fuel rates. Inspired by Scandinavian design, District Energy – one of the first hot water district energy systems in North America — launched in 1979 with Latimer as chairman. It added cooling in 1993, and later a renewable energy plant fueled by urban tree waste.

Latimer’s tenure also coincided with the development or redevelopment of major downtown office towers and public destinations, including the 38-story Wells Fargo Place, the Ordway Center for the Performing Arts, the first of two Securian Towers at 400 Robert St., the Town Square Tower, UBS Plaza and Landmark Towers.

During his mayoral term, he saw the potential for St. Paul’s Lowertown neighborhood in particular to host residences where law firms, factories, tanneries and retailers once stood, a gradual repositioning of the warehouse district that didn’t hit its stride until Coleman’s administration, long after Latimer left office.

“What George started, Chris Coleman kind of finished, in terms of development,” Melander said. “District Energy is recognized internationally for what it’s done. If you look at what’s happening with energy now, they were way ahead of their time.”

Not all of his projects bore fruit. Under Latimer, St. Paul competed against Los Angeles, Houston, Detroit and Miami to see which city would be the first to launch a “People Mover,” or mini-rail that would circulate in and around downtown from the Minnesota State Capitol and East Seventh Street to the Lafayette Bridge.

The proposal drew the ire of even some of his closest allies, including then-City Council Member Ruby Hunt.

Then-St. Paul Mayor George Latimer, left, talks with Joe Errigo, then head of an affordable housing agency, and then-Archbishop John Roach, in 1980. (Courtesy of CommonBond Communities)

“We clashed over the People Mover — it was a big deal,” said Hunt, interviewed in early August 2022 at the age of 98. “It was going to be running around downtown St. Paul, but people weren’t all that sold on it. Neither were the businesses.”

The project was officially nixed in 1980, but overall, said Hunt, “George did a beautiful job. He was an outstanding mayor. I worked together with him a lot. I had a lot of respect for him, and he had a lot of respect for me.”

“He was a real people person. He knew how to identify with people and get on the same wavelength, so to speak,” Hunt added. “George had the ability to attract and hire the very best people to run the city, and that’s an important trait that isn’t followed today as well as it could be.”

A run for governor

Latimer, then still mayor, took the politically risky move in 1986 of challenging Gov. Rudy Perpich, a member of his own party, only to lose to Perpich in the Democratic-Farmer-Labor primary. He would continue to serve as mayor until 1990.

After leaving office, Latimer served as dean of Hamline University’s law school from 1990 to 1993, and then as a special adviser to Henry Cisneros, President Bill Clinton’s Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, from 1993 to 1995.

Dignitaries posed for a photo during a groundbreaking ceremony for a new concert hall at the Ordway Center for Performing Arts in St. Paul, Minn., on Wednesday, June 19, 2013. From left is then-St. Paul Mayor Chris Coleman, Richard Slade, Jill Irvine Crow, former St. Paul mayor George Latimer, David Lilly Sr., David Lilly Jr. and Bruce Lilly. The new space would replace the soon-to-be-demolished McKnight Theatre and dramatically increase capacity. It has 1,100 seats, as opposed to the McKnight’s 306.

Over the years, Latimer became a visiting professor of urban studies at Macalester College, chief executive officer of the National Equity Fund – which manages low-income housing units in dozens of cities – and a regent with the University of Minnesota. The city renamed the downtown Central Library in his honor in 2014.

Also in 2014, Hunt and Latimer would both go on to take up residence at the Episcopal Homes senior living development on University Avenue near Fairview Avenue, just off the then-newly launched Green Line light rail corridor.

Melander, who befriended the former mayor in the 1990s and came to see him as something of a father figure, said Latimer sometimes reconnected with his older brothers, among others, through what the former mayor deemed “fellowship” and others called afternoon drinks. “I was his delivery boy during COVID, and prior, when he told me to go to Morelli’s (Liquors), if you know what I mean,” he deadpanned.

It was only in late 2022 when Latimer swore off the occasional cocktail and limited what had been his many daily social visits at Episcopal Homes that Melander began to become concerned about his friend’s health. Latimer would be moved to hospice care that year, only to move back out again within months, disenchanted with the notion that the end was nigh.

Changing social mores

During an interview with the Pioneer Press conducted in September 2020, well into the opening year of the COVID-19 pandemic and a few months after the death of George Floyd, a Black man, at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer, Latimer acknowledged that social mores had changed around him.

“There are any number of cultural and political practices that I have fully supported in my career, and now I’m being challenged in my thoughts,” he said at the time, noting his nuanced view of the social landscape.

“I believe there are some wonderful things happening within our culture today. We’re on our way of ridding ourselves of stereotyping people and ‘the other.’

“I think it’s quite beautiful when one of our grandchildren has their friend coming over, and I have no idea what color that person will be, or what gender they have. That isn’t the first thing they think of. People my age, we usually began by thinking, ‘He’s my friend, and he’s a Lutheran …’ Or ‘at the university, I was with a Black guy …’

“Whether we meant it pejoratively or not, it was our way of introducing our knowledge of people. And the younger people are ridding themselves of that. And that’s a plus.”

While acknowledging the racial fault line in police-community relations, he went on to criticize the wholesale rejection of police and policing.

“Racism — including ‘driving while Black’ — has a long history. But for an awful lot of folks as we were growing up, the police were not the enemy. Reform has been occurring, but because we’re a localized police system, it’s very mixed and varied.”

“There are many communities that have done community policing for many, many years,” Latimer said. “Does it mean it ends crime? No. But the trust level between the police and the people they’re protecting is important. This anti-police conduct is not liberal. It’s not democratic.”

In November 2017, Latimer penned a guest editorial in the Pioneer Press dedicated to the mayor-elect, urging whomever won the election to see their role as an ambassador between cultures, as much as a chief executive or technical officer overseeing city departments.

“Too often when people speak of the sense of community, they mean it exclusively, or in an elitist way,” wrote Latimer at the time. “They say whoever was here first is ‘the community’ and whoever comes later ought to stay for only a short while or immediately take on all the characteristics of those who came before them, abandoning any unique culture.”

“There are multiple communities in St. Paul where there are high levels of trust and a great love of the sense of place,” he continued. “An important part of the mayor’s job is to be a bridge builder between all of those wonderful communities.”

Funeral arrangements are yet to be announced.

Related Articles

Michael McGuire, ‘the most influential architect in the St. Croix Valley,’ dies at 95

Obituary: Karen Hubbard, longtime St. Croix River Valley matriarch, dies

Gena Rowlands, acting powerhouse and star of movies by her director-husband, John Cassavetes, dies

‘Someone who lived and loved deeply’: Former Pioneer Press, Star Tribune reporter Jennifer Bjorhus dies at 59

Obituary: Marine on St. Croix’s Ralph Malmberg, the inspiration for ‘Ralph’s Pretty Good Grocery’