Cerullo: Negro Leagues museum a must see for baseball fans

KANSAS CITY — As anyone who has visited Fenway Park can appreciate, there are some historic venues that every sports fan should try to visit. Places like Wrigley Field in Chicago, Lambeau Field in Green Bay, and if you’re a college basketball fan, Allen Fieldhouse at the University of Kansas.

Needless to say, when news broke this past summer that UConn and Kansas men’s basketball had agreed to a home-and-home and that my Huskies would be flying out to Lawrence in December, I knew I had to be there.

Upon booking my flights, I quickly realized the trip presented another bucket list opportunity.

Related Articles

Red Sox trade ‘Password’ to Pirates for RHP Johan Oviedo

Boston skyline’s iconic CITGO sign will soon be moved and rebuilt

New Red Sox pitcher explains why he wouldn’t mind allowing a few more walks

Top Japanese free agents for Red Sox fans to keep an eye on

Red Sox All-21st Century Team: Boston’s best from the last 25 years

Kansas City is home to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, which for more than three decades has preserved and told the history of Black baseball in America. I’ve always wanted to visit, so last month I reached out to Bob Kendrick, the president of the NLBM, and he was gracious enough to meet me and show me around when I flew in on Tuesday.

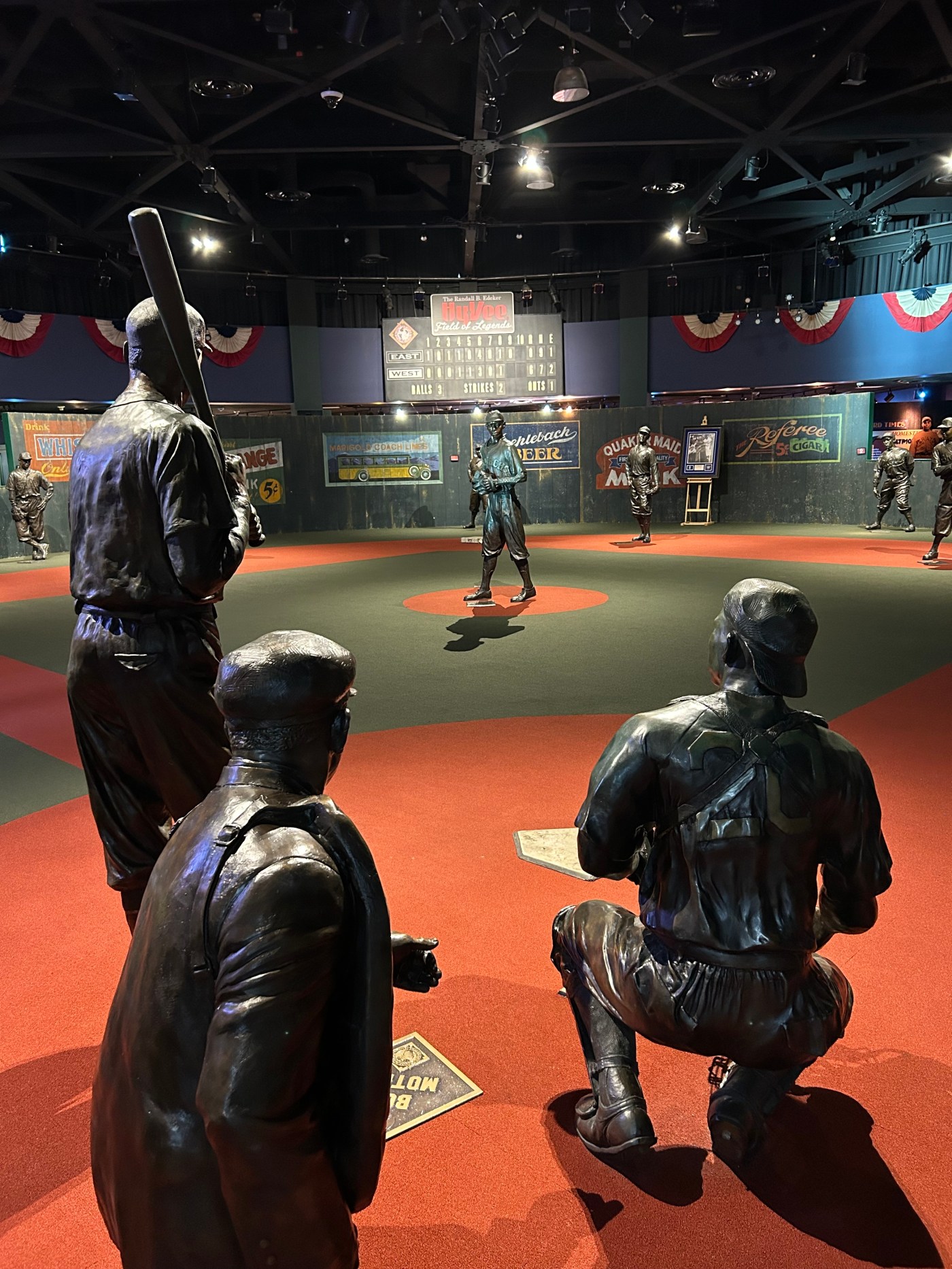

The first thing you see when you walk in is the Field of Legends, which features 10 life-sized bronze sculptures of Negro Leagues greats arranged on a mock baseball diamond. But visitors can’t just walk onto the field, not right away. As Kendrick put it, they are segregated from the field by a screen of chicken wire — much like Black fans used to be at Major League Baseball games, and in a larger sense like those players were denied the opportunity to play in MLB.

The only way to reach the field is by proceeding through the exhibits and learning the story of the Negro Leagues.

“I think this is one of the most incredible stories of hope, courage, determination, passion in the annals of American history,” Kendrick said. “These tremendously talented and courageous athletes forged a glorious history in the midst of an inglorious time in American history, and their story comes to life here.”

Originally established in 1920 by Hall of Fame player, manager and executive Rube Foster, the Negro Leagues provided a home for Black players to showcase their talents during the pre-integration era. Foster’s Negro National League was the first of seven leagues now recognized as major league caliber by MLB, and while the leagues faced frequent challenges and adversity, they existed for nearly 40 years, including for more than a decade after Jackie Robinson famously broke MLB’s color barrier in 1947.

Throughout their existence, the Negro Leagues held their own World Series and their own All-Star game called the East-West Game. The leagues innovated numerous advancements, including the Kansas City Monarchs becoming the first to play night games using artificial lighting in 1930, five years before the Cincinnati Reds did so at Crosley Field in 1935.

The leagues also welcomed players from Latin America and even featured three women. The first of them, Toni Stone, was signed to replace Hank Aaron after he left the Indianapolis Clowns to join the Boston Braves.

Outside official league games, Negro League clubs frequently held barnstorming exhibitions. The Philadelphia Royal Giants held a tour of Japan seven years before Babe Ruth famously visited the country, and the aforementioned Clowns became baseball’s equivalent of the Harlem Globetrotters.

The Negro Leagues entered a period of decline after Robinson debuted for the Dodgers, because once the color barrier was broken Black players started getting more opportunities. Larry Doby became the second Black player to join an MLB roster, signing with the Cleveland Indians weeks after Robinson’s first game. Other clubs followed suit until the Red Sox became the last MLB team to integrate, calling up Elijah “Pumpsie” Green in 1959.

But while Robinson’s arrival in Brooklyn precipitated the end of the Negro Leagues, his wider impact was much greater. Kendrick asserts that Robinson’s breaking the color barrier wasn’t just a part of the Civil Rights Movement, but the beginning of it.

Robinson’s debut predated major Civil Rights moments like President Harry Truman’s integrating the armed forces in 1948, Rosa Parks’ refusal to move to the back of the bus in 1955 and the March on Washington in 1963. His presence on the sport’s biggest stage sparked national conversation and debate, which over time led to greater societal change.

Beyond his role in shaping American history, Robinson owns the distinction of being one of 44 people associated with the Negro Leagues to earn induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Another is Buck O’Neill, whose career in baseball as a player, coach, manager and executive spanned eight decades and who played an integral role in the NLBM’s founding in 1990.

O’Neill was inducted posthumously into Cooperstown in 2022 as part of the same class as David Ortiz, but he nearly earned the call while still living as part of a special ballot in 2006. Though 17 Negro League players were elected, O’Neill fell one vote short, and Kendrick said having to break the news to his 94-year-old friend was one of the hardest things he’s ever had to do.

But, Kendrick said, rather than be angry or bitter, O’Neill instead expressed gratitude for the consideration and kept the focus on the 17 players that were elected, even offering to speak on their behalf at their induction ceremony in Cooperstown. He died two months after giving his speech.

Originally opened in a small single-room office by O’Neill and other former Negro Leaguers, the museum has grown over the years and now occupies a 10,000-foot space adjacent to the American Jazz Museum. Kendrick said they hope to expand again and are raising money to build a new facility that would triple the museum’s size and allow them to invest in new state-of-the-art technologies to better tell the Negro Leagues’ story.

As Kendrick and I reached the Field of Legends and the end of our tour, he called out the lineup of all-time Negro League greats preserved in bronze. Legends like Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson and Cool Papa Bell, who either never got the chance to prove themselves on the MLB stage, or didn’t until well after their prime.

There is a lot we can learn from those players and their stories, and I’d certainly recommend any baseball fan pay the museum a visit should they ever find themselves in Kansas City. But as Kendrick put it before we parted ways, the story of the Negro Leagues is much bigger than baseball.

“For those who are baseball fans you’re going to meet some new baseball heroes, but what I love about this museum that you don’t have to be a baseball fan,” Kendrick said. “Because if you’re a fan of American history you’re going to love this museum, and if you’re a fan of the underdog overcoming adversity to go on to greatness, you’re going to love this museum.”