Boston commercial properties hit with ‘hidden tax’ spikes after appealing city assessments

Commercial property owners in Boston claim they’re getting hit with a “hidden penalty” after filing abatements with the city, by way of assessed value being added to their buildings that’s leading to significant spikes in their property taxes.

Daniel Swift, a principal at the global tax consulting firm Ryan that represents a number of commercial property owners in Boston, crunched the numbers after hearing of the situation from his clients and found the startling trend, which comes at a time of downturn for the city’s commercial real estate market.

“It’s very unusual,” Swift told the Herald. “I’ve never seen it anywhere else in Massachusetts. I hadn’t seen it in Boston up until fiscal ‘24. They’re now penalizing you for filing an appeal on your subsequent year’s assessment.”

While property owners in Boston file abatements to seek tax relief when they feel their residential or commercial properties have been assessed higher than the fair market value, commercial property owners of late have seen the city instead add assessed value to their buildings, after filing an appeal with the state’s appellate tax board, according to Swift’s analysis.

The so-called “hidden tax” penalty is listed as an “ATB dispute,” per a property record card for a Seaport office building that was reviewed by the Herald. Per Swift’s analysis, it has added anywhere from a few hundred or thousands of dollars to up to close to $400,000 of additional property taxes for different commercial parcels.

“There’s been no notice of this,” Swift said. “I’m looking for notice. I’ve asked for it. I have found nothing. There’s no policy out there about how this all operates.”

“The only way for a taxpayer to become aware of this,” Swift said, is by going to City Hall, asking for a property card, and looking for a section that lists an ATB dispute override, “if you filed in the prior year and property was declining in value.”

The Seaport property card with an ATB dispute reviewed by the Herald, for example, shows an additional $14.4 million in assessed value was added to that property in late 2023, to bring the total assessed value to $482.1 million.

That translated to an additional $374,129 in property taxes in fiscal year 2025, as a result of the owner’s FY24 appeal for that Seaport property, Swift said. The building owner requested that identifying details be kept private.

The penalty is only being applied to properties that are declining in value, with the appeals centering around owners who believe that their properties have declined further in value over the past year than reflected by the city assessment, Swift said.

“There’s no comprehension of how they’re calculating these penalties,” Swift said, adding that the dinged properties are “strictly in penalty for filing that appeal to the appellate tax board.”

Swift’s analysis shows that for fiscal year 2025, the City of Boston adjusted office property tax assessments downward — by approximately 4.5% for Class A office properties and 12.8% for Class B/C office properties, on average.

Despite these adjustments, his analysis of downtown office sale transactions over the past two years indicates property tax assessments have exceeded sales prices by an average of 37%.

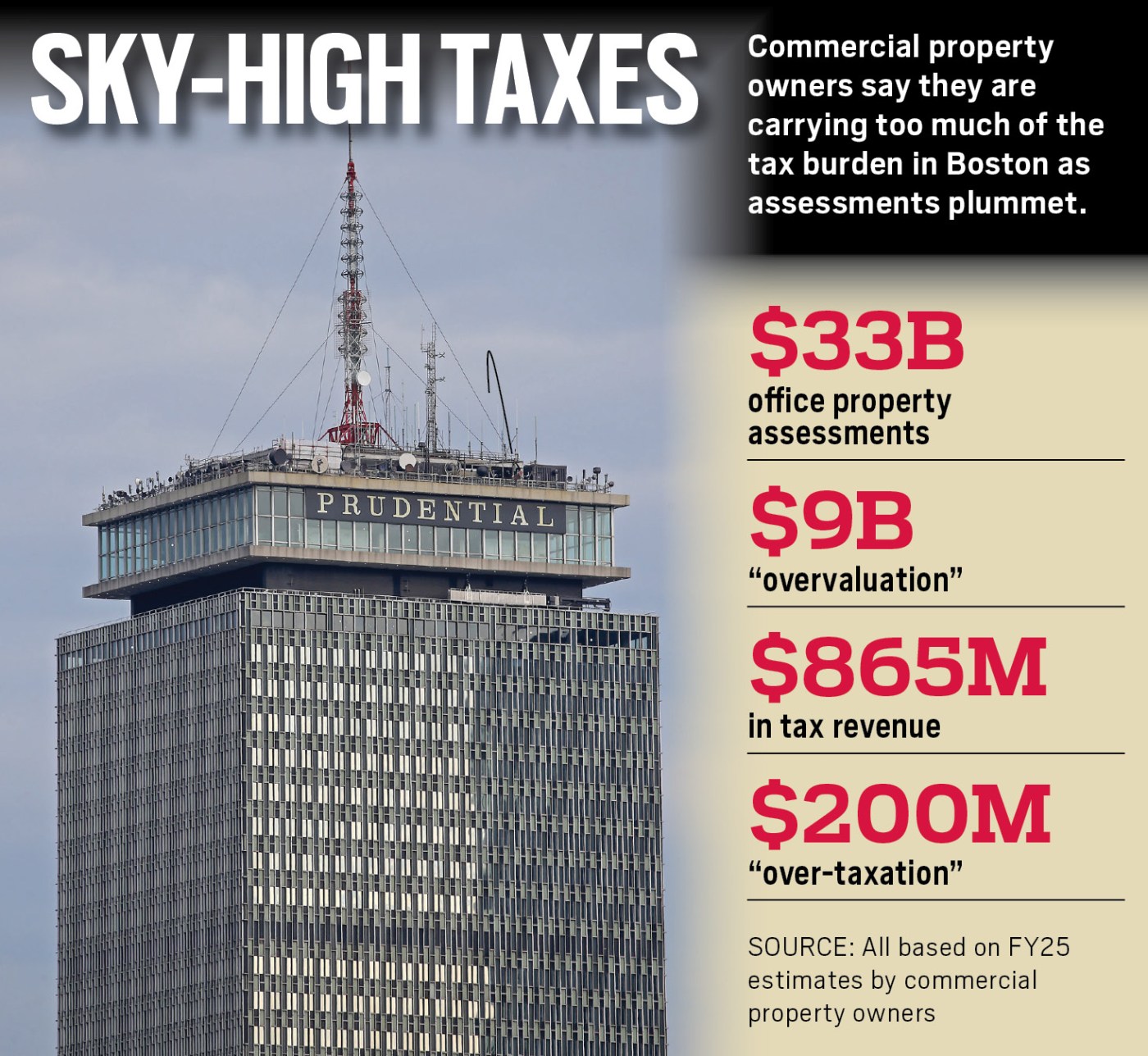

Office property tax assessments for fiscal year 2025 totaled roughly $33 billion, generating approximately $865 million in property tax revenue for the city, per figures provided to the Herald.

Applying the 37% over-assessment average across the entire office property class suggests an overvaluation of roughly $9 billion and an associated over-taxation of more than $200 million, per Swift’s analysis.

“The law clearly states that assessments are to reflect fair cash value … of the preceding Jan. 1,” Swift said. “There’s nothing that allows assessors to add on millions of dollars in assessment directly because of an appeal being filed because they felt that the value was excessive in the first place.

“There’s constitutional issues with this,” he added. “There’s due process issues with this. There was no notice provided to any taxpayers of this. I can’t effectively counsel my clients on what the consequences will be today if they file (an abatement) on fiscal 2025, and what happens to them next year, because it’s being applied in a subsequent year.”

Swift’s analysis comes at a grim time for the city’s commercial real estate market, which is grappling with empty office space and falling values due, in part, to changing post-pandemic work patterns.

The Boston Policy Institute published a report last Thursday that shows office values are falling at a steadier clip than it projected last year, at 35-45% versus 20-30% over the next five years.

That decline could push the city’s budgetary shortfall to $1.7 billion over the next five years, compared to the $1.2-$1.5 billion that was projected by the watchdog group in an initial report last year.

It also comes after a yearlong battle by Mayor Michelle Wu to combat the impact falling commercial values are having on the city’s budget — which derives roughly three-quarters of revenue from property taxes — by seeking a temporary change in state law that would allow the city to shift more of its tax burden from the residential to commercial sector.

The tax shift legislation is stalled on Beacon Hill amid steady opposition from the commercial sector and some elected officials who felt the city should cut the $4.8 billion budget —which grew by 8% this fiscal year with a 4.4% proposed hike in the next year that begins July 1 — instead.

Related Articles

Battenfeld: Wu now Trump public enemy number one, posing dilemma for Kraft

Boston Mayor Wu blasted by feds for comparing masked ICE agents to neo-Nazi group

Boston facing $1.7B budgetary shortfall from empty office buildings: Report

Battenfeld: Michelle Wu has her own ‘secret’ police problem

Maura Healey delivers millions to boost downtown Boston housing revival

Swift said, however, that the abatement dispute override mathematically blunts the tax impact on homeowners, which was the intent of Wu’s tax proposal.

“I have no idea what the intent is,” Swift said of the hidden penalty. “Mathematically, because you’re adding these artificial assessed values due purely to appeals — they’re tied only to appeals and you’re adding that value onto the commercial — you are increasing the commercial allocation and shift of taxes, and decreasing the residential as a result.”

The Wu administration disputed Swift’s analysis.

“These assertions either misunderstand or ignore the specific requirements in state tax law defining how cities assess and finalize valuations,” city spokesperson Emma Pettit said in a statement. “The City of Boston follows all state law when assessing values, and all values have been certified by the State Department of Revenue.”

The mayor’s office quoted a prior ruling from the Supreme Court of Massachusetts, which, per the city, has stated, “The assessors must determine a fair cash value for the property as a fee simple estate, which is to say, they must value an ownership interest in the land and the building as if no leases were in effect.”

“Because of state law,” the mayor’s office said, “values are determined using market rate leases, market rate expenses and market rate capitalization rates not sales for office buildings.”