State data raises questions of bullying reporting a decade after landmark anti-bullying law

According to records examined by the Herald, 91 out of 396 school districts in Massachusetts reported no bullying incidents to state officials in the 2023-24 school year.

The wide swath of no reports left at least one expert questioning whether local officials were clear on what kind of bullying needs to be reported under the state’s stringent anti-bullying law.

“Any school that says they have no bullying, I would say they’re lying, or they have an absolute failure to understand what bullying really is,” said Barbara Coloroso, author, speaker and consultant on bullying.

For just over a decade Massachusetts has had one of the best ranking anti-bullying laws on the books.

Each year, Massachusetts schools are required to report bullying allegations to the state. In school year 2023-24, the state Department of Elementary and Secondary Education reported 8,421 total bullying allegations at public schools. The student population of Massachusetts public schools was just under 900,000 in the 2023-24 year.

The state’s data shows a total of 739 public students in the 2023-24 school year were disciplined for bullying via suspension, expulsion, removal or arrest.

The same year though, 91 of the total 396 school districts, charter schools and vocational schools reported zero allegations of bullying incidents, according to DESE data.

Those figures raised the question of whether there may be an issue of underreporting.

Massachusetts state law defines bullying as “repeated use by one or more students or a member of a school staff of a written, verbal or electronic expression or a physical act or gesture” resulting in consequences like physical or emotional harm, damage of property, a hostile environment or infringement on the target’s rights.

Coloroso highlighted the “repeated” aspect of Massachusetts’s definition, noting she recommends states include repeated behaviors but also allow consideration of one-time events.

“It can be a one-time significant event,” said Coloroso. “Bullying in itself, is about arrogance and contempt for another human being, dehumanization, and the like. It doesn’t have to be repeated over time.”

If a kid’s head is dunked in the toilet, she noted, “you need to treat that as bullying, not wait for it to happen twice.”

A 2023 federal survey of the state estimates 15.9% of public and private school children in Massachusetts report being bullied, according to the CDC Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) data, which could equate to about 150,000 school children in Massachusetts based on the 2023-24 population.

Massachusetts state law also mandates schools conduct a survey once a year including topics of safety and bullying, reported annually in the Views of Climate and Learning (VOCAL) Survey Project.

In 2024, 16% of 10th grade students said it is “always or mostly true” they have stayed home or avoided schools because they don’t feel safe. About the same percentage answered it was “always or mostly true” they had been teased or picked on about their sexual orientation and race or ethnicity more than once.

Asked if they had been called names or made fun of more than once in school, 43% of 8th graders in 2024 answered in the affirmative categories. Close behind, 29% answered affirmatively they had seen rumors or lies spread about them on social media more than once.

In the younger 4th and 5th grades, 8% and 12% of kids respectively indicated they feel unsafe at school in the 2024 survey.

Meghan McCoy, manager of programs at the Massachusetts Aggression Reduction Center, said their research has shown consistently about two-thirds of initially reported bullying typically “doesn’t align” with defined bullying even in instances when it’s not an “ok behavior.”

“There may just be schools and districts that have a lot of prevention in place, and so are addressing things before it rises to the definition of bullying involving the repetition, power imbalance, and intentionality of the behavior,” McCoy said, noting a shift in Massachusetts to districts understanding a “role of protecting the mental health of students.”

Recently, McCoy said, the center has been less inundated with requests from districts, as schools have dealt with “a lot on their plates,” especially with funding and resources.

The Massachusetts anti-bullying law, which was first passed in 2010 in response to the death of 15-year-old Phoebe Prince and later updated with a 2014, mandates school districts develop “bullying prevention and intervention plans” meeting strict requirements.

Under the law, districts must also report bullying allegation, substantiated incidents, punitive actions to the state, and a survey on bullying to the state. The districts are required to notify victims of bullying and their families of DESE’s Problem Resolution System, which may also investigate incidents of bullying.

Outside of DESE, the Attorney General’s Children’s Justice Unit has responded to at least 151 school bullying complaints since 2016.

In one incident — involving a “mock slave trade” organized by 8th graders on Snapchat in February 2024 within Southwick School District — the AG unit issued an action plan mandating trainings for parties from district leadership to the perpetrators and continued oversight through 2026.

Despite continued incidents and low reporting among districts, Massachusetts has one of the most thorough anti-bullying laws on the books, experts said.

Massachusetts’s law meets all 13 of the components outlined in federal guidelines for state anti-bullying legislation, including reviews and updates of local policies, reporting and investigations, and prevention education. In just the New England area, Connecticut and Rhode Island also meet all the criteria, while New Hampshire, Vermont and Maine miss at least one.

“You complied with all of it,” said Coloroso of federal guidelines. “The key is, do they follow through? That’s been a weakness throughout because, for instance, a state may keep track of bullying incidences, but if you don’t consider it bullying to begin with, or you categorize it as a conflict when indeed it isn’t, then you don’t have to report it.”

Massachusetts has trended down in terms of bullying since the implementation of the first law, according to the CDC’s YRBS data, dropping from 19.4% of students reporting being bullied on school property in 2009 to 15.9% in 2023. The state remains well below the national average of 19.2% of school kids in 2023.

Related Articles

Some states reexamine school discipline as Trump order paves go-ahead

Rapidly expanding school voucher programs pinch state budgets

Belgian princess left in doubt about her Harvard future following Trump’s foreign student ban

China criticizes US ban on Harvard’s international students

Trump administration says Columbia violated civil rights of Jewish students

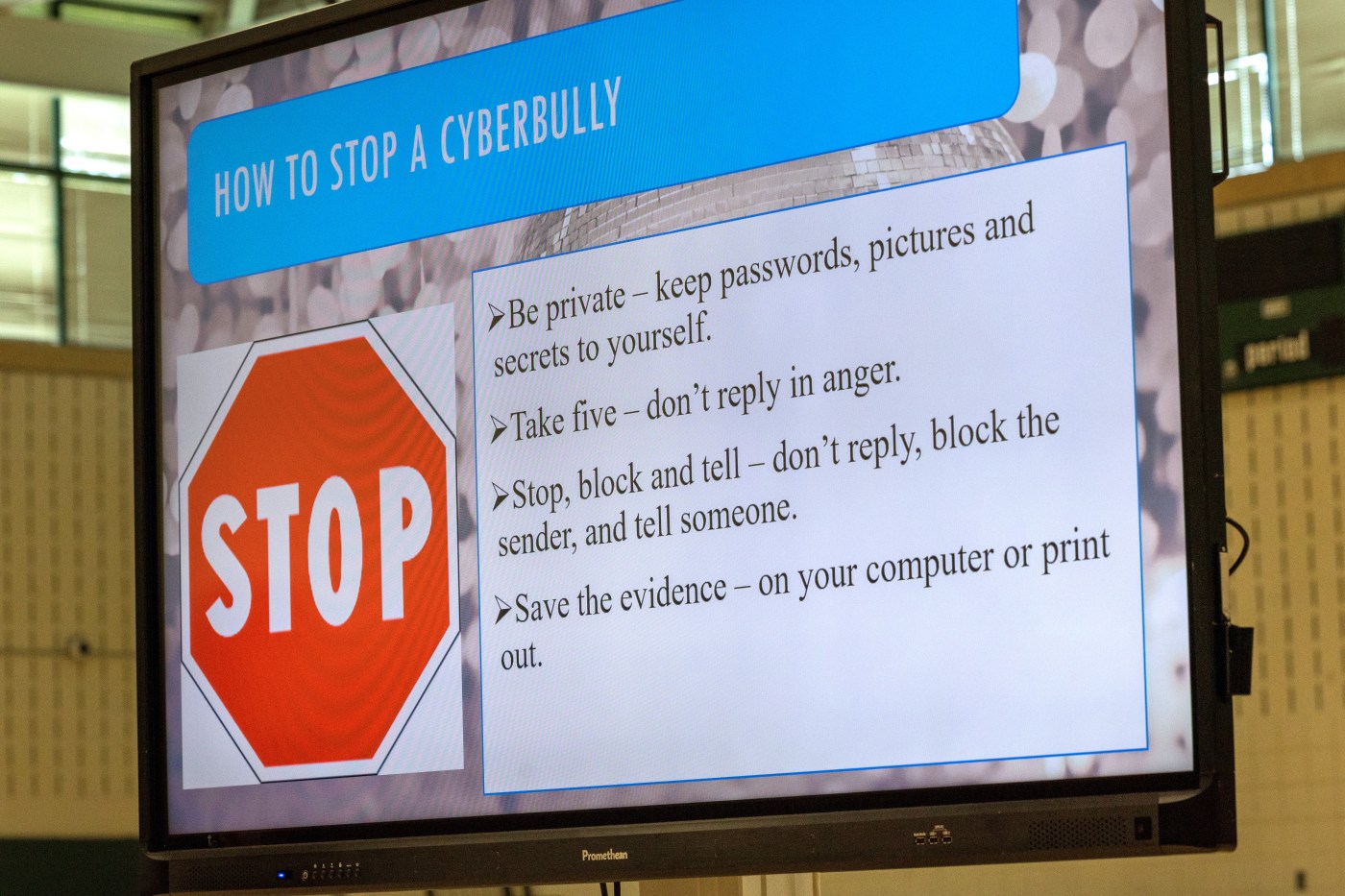

As the landscape of bullying changes, the reports of cyberbullying in the states are trending the opposite direction. From 2013 to 2023, students who reported being electronically bullied rose from 13.8% to 15.3%, according to the CDC YRBS data.

“The future of really creating a shift is, I really think it’s going to have a lot to do with bigger shifts in the sense of managing the time that our kids are spending on their phones and on social media, and helping to give them time to practice their social skills early on,” said McCoy. “There are pretty deep structural changes that can’t be ignored.”