Moving to France for 6 months taught Shoreview man about wine, food and belonging

Steve Hoffman was living a very ordinary life in Shoreview when he decided to do something quite extraordinary in 2012 — take a six-month hiatus from his job and move his family to the rural French countryside.

The father of two insists it’s not as crazy as it sounds. A lifelong Francophile who speaks fluent French, the 59-year-old tax preparer has never forgotten the summer he spent in Paris during college interning for the Little Brothers of the Poor.

Also, he and his wife, Mary Jo, a former rocket scientist-turned-visual artist who shares his love of travel, spent an enjoyable summer in Brittany when their daughter, Eva, was 6 and their youngest child, Joe, was a baby.

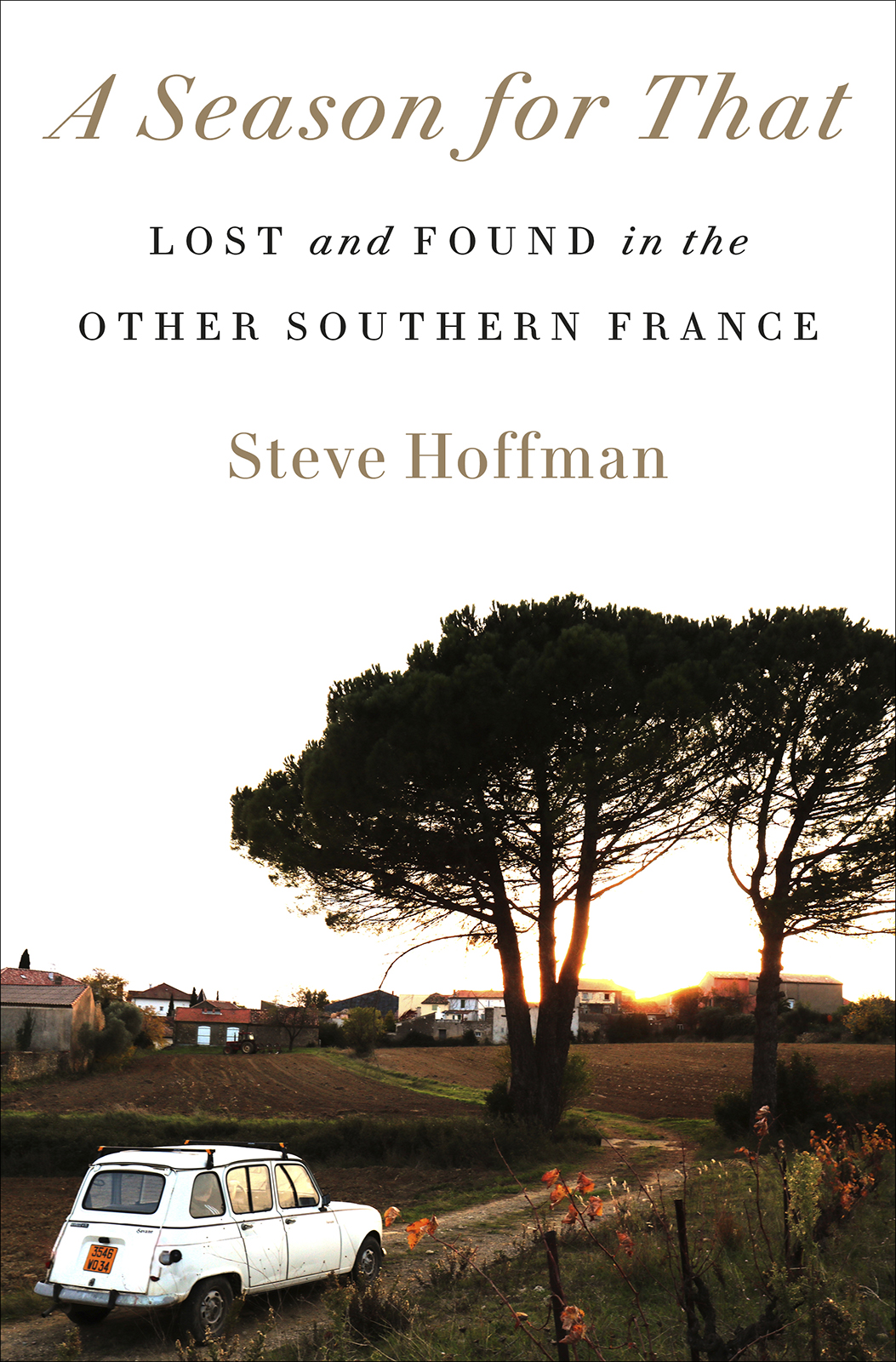

“A Season for That,” by Steve Hoffman. (Penguin Random House/TNS)

As he writes in his memoir, “A Season for That: Lost and Found in the Other Southern France” (Crown, $30): “The casual bravado it took simply to say, ‘[Screw] it, let’s do it’ brought out something that inspired us and made us each excited to be the other’s partner…. If it all ended in a heaping pile of crap, we would laugh, and have a good story to tell.”

“There was this spirit behind our trip to Languedoc. We had done this kind of thing. We could do it again,” he said in a phone call from New York City.

Additionally in their favor: Tax work is seasonal and the couple had saved, which meant Hoffman could take time off from work, and their two kids had received their elementary education at a French immersion school in St. Paul.

Il est temps de vivre le rêve! Time to live the dream. But practically, as equal partners.

“We had sort of an aha moment. There came a point where we looked at each other and thought, Eva had just been born and was now a pre-teen, and oh my, in five years she’ll be out of the house like a lightning bolt.’

“If we were going to be the kind of family we wanted to be — close, engaged, adventurous — we needed to stop and turn inward and focus on having an experience together that will enrich the family.”

The goal was two-fold: to cement their kids’ French education while also “practicing” for Act 3 of their lives by getting good at something that would fill their souls and enrich their lives when Act 2 came to an end.

“My journaling and her photography were born in that trip,” he said. “Yes, we wanted to be part of the village but we were also preparing for retirement.”

As you page through the early chapters of the book — or better yet, listen to Hoffman read it on Audible — it might seem like the family’s half-year soujourn to tiny Autignac, in the Languedoc region of southern France, was going to be a complete bust.

Their landing in summer was both hot and “loud with insects.”

The breakneck French dialect spoken by the tiny village’s 800 residents sounded nothing like the high literary French with a Parisian accent Hoffman learned in college.

The stone winemaker’s house the couple rented from an Irishman was a “bit more IKEA” than the idealized abode of French fairytales (but at least had a great terrace for drinking wine together).

And the cheese? It was strongly flavored and reveled in “stinkiness.”

But the real issue was this: Despite being fluent, Hoffman couldn’t bring himself to engage in conversation with their new neighbors.

He was, Mary Jo recounts in the book, a man who “can’t get over himself, can’t let go … a man who can’t ask for ice for his kids’ Cokes for Christ’s sake, because it might make him look like an American in France, which is exactly what he is.”

During our conversation, Hoffman admits his wife was on the money.

“I’d go to the boulangerie and the baker was there with her family and a same-age daughter but I was too embarrassed, too shy, too whatever, and never asked if they could play…. I just wouldn’t get out of my comfort zone to make connections to make it meaningful. I didn’t integrate in any way.”

It wasn’t until a village fete just before la vendange — the fall grape harvest — that Hoffman found his seminal moment. He asked his friend and neighbor Jean-Luc, a vitivulteur with an encyclopedic knowledge of vines and their care, if he could help with the thankless, back-breaking work of grape picking and other jobs that happen over the course of the harvest.

“I knew I had to take a much bigger step” in trying to integrate, he said.

Jean-Luc agreed and before long, Hoffman was spending most of his mornings among the weed-choked vines and afternoons in the winery, learning the art and science of winemaking.

“I was no longer this tourist but a co-worker and peer,” he said. “It was a signal from me to them that I was taking this seriously, to be in this place on its terms and the people who live there.”

As days stretched into weeks and then months, he discovered an open heartedness within himself he hadn’t expected, and became one with the culture. By the end of the book, instead of sticking out like the foreigner he was, he had woven himself and his family into the fabric of the community.

The kids not only cemented their French education but made friends; Mary Jo’s blog, called STILL, was evolving into the beginnings of her own book; and Hoffman — who now volunteers as a grape picker and winemaker’s apprentice — learned to let go of his preconceived notions of what it means to be French.

“A huge amount of what I learned in many lessons over the course of the trip were about letting go and allowing [myself] to be ignorant, and allowing people to open up and make room for us in this place.”

One daily task that made life easier, he said, was cooking for the family. With time on his hands, Hoffman spent hours poring over recipes in French cookbooks and on French blogs, which he then cooked using seasonal ingredients from local vendors and the village’s only grocery store. That meant a lot of very bad meals before the unfamiliar ingredients felt natural to him.

By the time they left, he was whipping up dinners any French cook would be proud of — simple but flavorful local dishes that were very different from what they’d eaten in the U.S. but felt like comfort food, “which was really thrilling,” he said.

RELATED: Pasta and clams ã la famille Hoffman offer a taste of France

Hoffman’s elegant, often lyrical, prose transports readers to the French countryside, where grapevines fuel cooking fires, fragrant rosemary blankets the ground, villagers buy their fish from local fishmongers on Fridays, and a warm baguette is just a short morning stroll to the village’s main square.

Along the way, we meet a cast of charming characters that embody the French spirit — Jean-Luc and his wife, Nicole, who lead him into the world of winemaking; Marie, proprietor of the local grocery store who shares secrets of French provincial cooking; Andre, the vigneron who makes the traditional wines of Languedoc in the traditional way; and Thierry, the vigneron and wine broker striving to make some of the highest-rated wines in the entire region.

We also follow along as Eva and Joe, a sensitive kid who finds joy in studying praying mantises and other insects, adjust to going to school and making friends in a French town that is “big enough to have a bakery and small enough to be ignored by guidebooks.”

Equal parts travelogue and memoir, the book, which took 10 years to write, grew out of the many journals he kept during their time in Autignac and turned into a three-part series for the Minnesota Star Tribune in 2013. His editor was The Splendid Table host Francis Lam, who he met at an event in New York.

“It took time to do justice to that time and place and what happened,” Hoffman said of the decade he spent writing and rewriting each sentence to give it emotional heft. “I knew it was important, but couldn’t quite put it into words.”

Over time, he became not just a food writer with stories in Food & Wine, The Washington Post and other publications, but also an award winner. He won an IACP Bert Green Award for narrative culinary writing in 2014, and was the 2019 winner of the M.F.K. Fisher Distinguished Writing Award at the James Beard Awards.

As for the future? He still very much enjoys his surprisingly intimate work as a tax preparer, and the relationships it forges with people and families. And he’s still writing. For a piece in Food & Wine’s holiday issue, he explores the duck and goose “fat fairs” held in France each winter and he’s pondering a new book on masculinity in this, the third act of his and Mary Jo’s lives.

Related Articles

Shoreview author’s pasta and clams recipe offers a taste of France

Travel: These cruise ships will make their maiden voyages in 2025

10 hot new West Coast hotels and restaurants are headed our way in 2025

Disney cut back accommodations. What’s it like to attend while disabled?

Family travel 5: Read the book, then visit the setting

He and his wife are also still recovering from a massive fire that swept through their home on Turtle Lake’s south shore on Oct. 4, and made it inhabitable.

“We can already see that the fire is a clarifying event,” he said. “We will have to make some decisions about what our lives will be like, and put it back together in a very intentional way.”

The kids are thriving, too. Now 21, Joe is studying the business of design at New York University while Eva, 26, is working on a degree in design at Stanford University.

“[The trip] was imposed on them to some extent, but they look back on it fondly now,” Hoffman said. “All of their biggest loves date back to the trip. They understand something changed for the good.”

He’ll always be a Minnesotan, “but I also found a spiritual home in France that I can’t deny.”