Catholics exhume Duluth priest who may become Minnesota’s first saint

DULUTH — There are over 10,000 canonized saints in the Roman Catholic Church, and none of them are from Duluth. In fact, none are from anywhere in Minnesota, and only a dozen can even be considered American.

The closest thing to a hometown hero Northland Catholics can claim in the pantheon of official saints is Mother Cabrini (1850-1917), who worked in Chicago. Then there is Solanus Casey (1870-1957), who has been beatified; he was born in Oak Grove, Wisconsin, and spent a short time in Duluth.

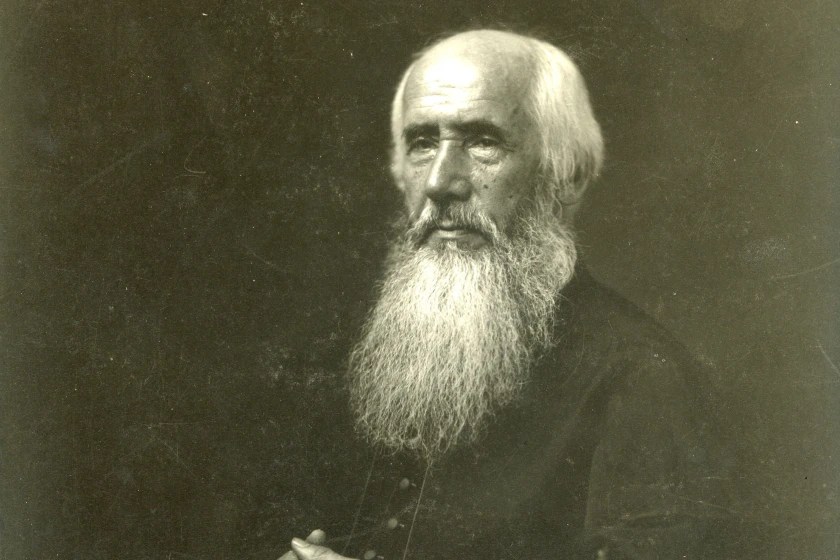

So it would be a big deal if Monsignor Joseph Buh (1833-1922) achieved canonization.

“As far as actually spending a lot of time in the state of Minnesota,” said Fr. Richard Kunst of Duluth, “he would be the only one.”

It may be a long shot, but Daniel Felton, Bishop of Duluth, feels the time has come to ask whether Buh is worthy of sainthood. In July, the Diocese of Duluth exhumed Buh’s remains from Calvary Cemetery in preparation for eventually re-interring the missionary priest at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Rosary.

That step alone is a mark of the esteem Felton and his fellow Catholic leaders have for Buh. Kunst, who has been asked by Felton to lead the process of publicizing Buh’s story, said no other area Catholic has received similar treatment.

“We exhumed him to bring him to an appropriate place because he’s the patriarch of our diocese,” said Kunst. “He helped establish 50-some parishes.”

Buh was born in Slovenia and developed an interest in missionary work. He arrived in Minnesota in 1864, ultimately becoming a pivotal figure leading the establishment of Catholic institutions across the northern part of the state. In doing so, he worked with the Ojibwe and with the rapidly expanding populations of immigrant settlers.

“Bishop Daniel Felton is very much of the mindset of our diocese being a missionary diocese,” said Kunst, and “Monsignor Buh (is) the primary missionary that our diocese has ever had. … He’s the perfect role model for our diocese.”

Buh’s missionary spirit is relevant today, said Kunst, in inspiring the faithful to be forthright in sharing their beliefs.

“Anybody within our realm as priests, whether they’re Catholic or not, we have a certain responsibility for their spiritual well-being, and that’s what a missionary is,” he said. “Bringing (Jesus) Christ to people doesn’t mean you have to travel to a far-off land.”

“There’s an evangelization movement among many Christian churches, but now among (Catholics), too,” said Sister Beverly Raway, Prioress of St. Scholastica Monastery. With that comes an interest in “recognizing those leaders from the past who spread the faith.”

The Sisters of St. Scholastica have long nurtured a special connection to Buh, working to keep his memory alive for the past century. “There was a great friendship between Mother Scholastica, the founder of our community, and Monsignor Buh,” said Raway.

At one point, a Sister of St. Scholastica “found one of his shirts, a white shirt, and cut it into little tiny pieces and attached it to prayer cards that were distributed among the sisters,” said Raway. “I’d love to know if there are any of those still around!”

Two members of Raway’s order, Sister Bernard Coleman and Sister Verona LaBud, wrote a biography of Buh: “Masinaigans: The Little Book” (1972). The book’s title comes from an Ojibwe nickname for Buh, who was often seen carrying a small book — likely a breviary or, for the busy missionary, a day calendar.

Sainthood is ultimately conferred by the Pope, but it’s not simply an executive decision.

Advancing a candidate for the series of steps toward canonization involves documenting the deceased’s continuing impact on the lives of the living. In conferring sainthood, the church is officially agreeing that a person’s soul is in heaven with God.

Catholics who believe in the holiness of a person who has died don’t need to wait for a green light from Rome, though: They can start praying for the person’s “intercession” with God right away. In fact, that’s just what local Catholic leaders are asking people to do with Joseph Buh.

A newly produced booklet being distributed in the diocese contains a short biography of Buh, and has the words of a suggested prayer to Jesus requesting “that you make your goodness known by granting us through (your servant Joseph Buh’s) intercession the petitions we implore.”

Those who feel that Buh has interceded to bring about a positive result, even a miracle, are encouraged to share their stories.

Years before coming to Minnesota, Buh contacted another Slovenian missionary who had ties here. Bishop Frederic Baraga (1797-1868), Michigan’s famed “Snowshoe Priest,” is honored with a granite cross at the North Shore mouth of the Cross River, where Baraga completed a perilous crossing of Lake Superior by canoe.

Baraga is also being advanced for potential sainthood by his own devoted following and is much farther along in the process than Buh. In 2012, Baraga was declared venerable by Pope Benedict XVI. Baraga would next need to be declared blessed before becoming eligible for the final step toward sainthood, canonization.

The diocese booklet cites Buh’s particular impacts on “Native American and Slovenian immigrant communities.” James Lah, president of the Ely branch of the Slovenian Union of America, attested that Buh’s memory lives on in the Northland.

“His picture hangs in the basement of St. Anthony’s Church here in Ely. He looks like some Old Testament prophet,” said Lah. At times, a chalice owned by Buh circulated among Ely families, who used it as a sacramental object to pray for vocations.

Among Ojibwe, the missionary is seemingly less well-remembered. Kunst said he has not had conversations with Native community members regarding Buh, and two different experts in Minnesota Ojibwe history, when reached by the News Tribune, said they were unfamiliar with Buh’s story.

Anton Treuer, professor of Ojibwe at Bemidji State University, said he did not have enough knowledge of Buh to comment on that missionary specifically, but pointed to a passage from his book “Everything You Wanted To Know About Indians But Were Afraid To Ask.”

In a passage addressing the topic of Christian missionaries generally, Treuer wrote, “Missionaries were not simply evangelizing their faiths — they were colonizers.”

Many Indigenous people resented missionaries, though some adopted Christian beliefs. “Today,” wrote Treuer, “Native Americans have differing and sometimes conflicting views about the missionaries and the religions they brought.”

To Felton, Buh’s conviction in his faith and willingness to spread it is a signal of virtue. “Reflect on how he evangelized the people he served as a model for our own time,” encourages Felton in an introduction to the biographical booklet.

“It’s always going to be (relevant), whether it’s the 21st century or 20th century or any time, the idea of being a missionary,” said Kunst. “Bringing people back to Christ and bringing Christ to these people, that’s what Monsignor (Buh) did on a heroic level.”

Raway said St. Scholastica has supplied the diocese with archival materials to help tell Buh’s story. If Buh becomes recognized along the path to sainthood, she said, it would be meaningful to area Catholics.

“To have one of your own recognized just strengthens your own faith,” she reflected. “It just makes you feel, we can do it, too!”

Related Articles

What is the coolest product made in Minnesota? It’s up to you to decide.

Letters: ‘Hey Communists, go home!’ a male voice from the crowd yelled

Friends of Madeline Kingsbury recall witnessing abuse by accused killer

Minnesota enters second archery deer season with crossbows for anyone

Red Wing couple plead guilty to caging, abusing their 4 young children