TJ Klune says ‘Calvin & Hobbes’ inspired a ‘Somewhere Beyond the Sea’ character

When writing sequels in fantasy literature, authors can face a tricky challenge: How do you expand on the world you created in the first book without breaking any of the rules you set?

“If you have a really cool idea that goes against something in the first book,” author TJ Klune says with a laugh, ”you can’t do it because people will call you out for it!”

In 2020, Klune’s queer contemporary fantasy novel, “The House in the Cerulean Sea” arrived in bookstores to critical and popular acclaim, including landing on multiple bestseller lists, getting award recognition and building a community of fans on social media creating art, fan-fiction and love letters to the characters.

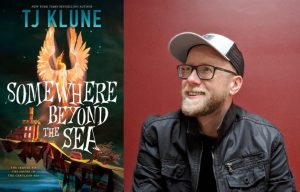

“House” centers around the lonely, uptight Linus Baker and his path to becoming a beloved member of a found family – a long way from his origins as a caseworker monitoring state-run orphanages for the Department In Charge Of Magical Youth (DICOMY). This branch of government, which underpins a system responsible for breaking apart families and sowing distance between magical people and humans, comes to the forefront in Klune’s sequel, “Somewhere Beyond the Sea,” out Sept. 10 from Tor.

“Somewhere” continues the story of the magical orphans on Marsyas Island – this time not from Linus’s point of view, but from that of the man he has found love with: Arthur Parnassus, orphanage manager and de facto father to six lovable, complicated children cast out by society. And while Arthur and Linus won the initial battle against DICOMY, the real war to tear down the system endangering their kids has only just begun.

In “Somewhere Beyond the Sea,” Klune revisits and expands the “Cerulean Sea” universe to explore resistance, solidarity and liberation. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. Were you always planning to write a sequel to “The House in the Cerulean Sea?”

This is going to sound kind of weird coming from me, but sequels suck to write. When you create a world in a book, you can make up any rule you want – but by the time you get to a sequel, you’re bound by the rules that you made in the first book. So I don’t really like writing them. I wasn’t planning on going back.

As you know, in the last few years we’ve seen the rising anti-LGBTQ movement – particularly the anti-trans movement – that is occurring across the United States and in the UK. It’s the same kind of morality panic that we saw in the ‘80s with the Satanic Panic, just dressed differently. So I decided that I needed to write a book – the sequel to “The House in the Cerulean Sea.” I wrote “Somewhere Beyond the Sea” as a celebration for trans people, for the queer community, for anybody who has ever felt like they’re not good enough, or has been told they’re not good enough.

Q. In “Somewhere Beyond the Sea,” resistance is a major theme, such as when Arthur testifies about his own past at a government hearing. Can you talk a bit about that?

In “The House in the Cerulean Sea,” an outsider comes in and realizes that he’s a cog in an uncaring machine. At the end of the day, Linus is an ally. He loves and wants to protect his family as much as possible, but he hasn’t had to walk a mile in their shoes.

“Somewhere Beyond the Sea” is about the machine itself, and what happens when you find your voice and start to push back against it. So it puts us into the shoes of Arthur, who has been othered his entire life and who has been beaten down because of who he is.

I was one of many who watched when transgender people, parents and guardians of transgender youth and doctors who provide medical and gender-affirming care were invited to testify in front of the government. During these testimonials, they were essentially ambushed by politicians who sat there and questioned their minds, their bodies and their right to exist. It was horrific, and it blew my mind that that is how we function these days.

I talked to some of the people who were involved in testifying, and asked them a bunch of different questions. One question that I made sure to ask throughout was: If you had to do this all over again, knowing the reception you were going to receive, would you do it? Every single one of them unequivocally said yes, because they got to speak their truth regardless of how it was received or regardless of the way that they were attacked. That is extraordinary.

Q. Was there a new character who was harder to write than you thought?

Yes – David the Yeti (a magical child whose parents were killed by hunters). Going into this book, I knew David would have to be as big a character as the other kids were. When you’re writing a story about kids going through trauma, you have to make sure that they still read and sound like a child and not a 40-year-old man. So I went back to one of my favorite characters in the entire world: Calvin from ‘Calvin and Hobbes’ by Bill Watterson.

Calvin has a very active imagination, and he plays different roles; one of those roles is a noir detective named Tracer Bullet. When Arthur and Linus meet him for the first time, David, who wants to be an actor, puts on a performance as a noir detective. He is, in essence, my version of Calvin.

As an author, I’ve been invited to speak to kids in classrooms around the world. People don’t realize that kids today are smarter than we ever were at their age. They see what’s happening, and they’re pissed off. One day soon, they’re going to be the ones making change. If we’re deciding who they can be, what they can read, who they can talk to – why is nobody asking them what they think about all this?

Q. What would you like readers to come away with?

After people read this book, I hope that they’ll be kinder to each other. We seem to live in an age where everybody’s outraged about everything. It’s not that hard to be kind to each other, and I think that we should all attempt to do that a lot more. In the book, Sal (one of the kids) very rightly calls out Arthur for putting himself in an echo chamber, for surrounding himself with people that only think like he does. I think about that a lot.

I think we can be better, and we can fix things that are broken. It’s going to take a hell of a lot of work, but we can do it – because there are so many things that make us more alike than there are that set us apart.

Related Articles

5 must-read books in translation chosen by Jennifer Croft

How Unabomber Ted Kaczynski loomed in the mind of an ‘obsessed’ novelist

Literary pick for Sept. 1

Literary calendar for week of Sept. 1

Readers and writers: Outside the spotlight, editor brought to life hundreds of stories