It’s ‘decimating our community’: Patients and staff on edge as Carney closure looms

Patients at Carney Hospital are scared of what might happen to them should a plan to close the Dorchester health center get the approval of a Texas judge, according to a long serving hospital employee who said lawmakers need to offer a better solution than just more talk.

On Monday, standing adjacent to Carney Hospital under a steady summer rain, U.S. Sen. Ed Markey, U.S. Reps. Ayanna Pressley and Stephen Lynch, joined by Boston Mayor Michelle Wu, State Sen. Nick Collins and members of the Boston City Council, promised a group of local residents, patients, and Carney employees that they would do everything in their power to prevent Steward Health Care from carrying through with their proposal to close Carney and another Massachusetts hospital after Steward failed to find qualifying buyers.

Stephen Wood works as a nurse practitioner in the emergency department at Carney Hospital, where he’s been employed off and on for the better part of 15 years. The last several months, he said, he’s been forced to spend time reassuring his patients over the fate of their health care.

“Our patients have had a lot of questions. They don’t know where they are going to go. The population we serve — we have a high immigrant population, a lot of people who are underinsured or not insured. We see a lot of people from Haiti that are seeking asylum, right? Those people have no idea where they are going to go and they are scared,” he said.

It’s not just the patients that have the jitters, Wood said, doctors, nurses, and even suppliers are looking elsewhere to do business.

“We have seen fewer and fewer resources,” he said. “It’s really decimating our community.”

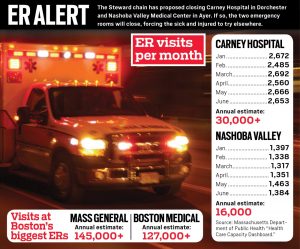

Lynch said the hospital, which annually sees 30,000 visitors and employees 750 people, is the “heart of our health care community” in Dorchester and in surrounding neighborhoods.

“The news of that closure was a real shock, a kick in the gut of the Dorchester neighborhood,” he said, pointing out Steward had failed to follow state laws which dictate 120-day notice ahead of a hospital closure.

Markey said he’s subpoenaed Steward CEO Ralph de la Torre and launched a congressional investigation into Steward’s practices, reiterating a previously made assertion that the exec will be made to answer for his “greed” and that he should be forced to sell his yachts while the proceeds are used to keep the hospitals afloat.

Pressley acknowledged the anger of the crowd, before issuing a “demand for accountability.” The congresswoman has been a Carney patient, she said, and knows how important the hospital is to the community.

Wood criticized the platitudes offered by the politicians as flowery rhetoric, for the most part, and said they cannot quiet the concerns of his patients.

Wu, speaking after the presser, said there is very little the city government can do to force a private business to continue its operations while they are actively pursuing a bankruptcy filing.

Nevertheless, her team worked to make the sale process as smooth as possible, she said, even though in Carney’s case that didn’t work out. At the city level, she said, there aren’t a lot of tools in the toolbox when it comes to regulating a state licensed hospital chain, but that the city is looking into every available option.

Lynch, Markey, Pressley, and Wu all said they wouldn’t allow the hospital to close if they have any means to prevent it. But without any plan announced at Monday’s presser, Wood said he’s not just going to take the lawmakers at their word.

“The only person I heard say anything that was of potential benefit was Senator Nick Collins, who said ‘let’s declare a state of emergency’” he said.

“We have Mayor Wu here. She could have done that today,” Wood said, frustrated.

Anyone who was paying attention could see Steward’s decision to close the hospital coming from a mile away, Wood said. Steward filed for bankruptcy protections in May, after months of reporting on the company’s inability to make its rent payments and meet its debt obligations.

“This has been in the works for years,” he said. “This is how the plan was set, from the beginning.”

Steward announced last week it would close Carney Hospital in Dorchester and Nashoba Valley Medical Center in Ayer. The company also operates Good Samaritan Medical Center in Brockton, Holy Family Hospitals in Haverhill and Methuen, Morton Hospital in Taunton, Saint Anne’s Hospital in Fall River, and St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center in Brighton. Those hospitals are due to be sold sold after an auction earlier this month. Details about the prospective buyers, however, have not been made public yet.

In the interim, the Healey Administration has indicated it will provide Steward’s Massachusetts hospitals with $30 million in “interim” state aid — which they would have been owed eventually — to help shore up the facilities’ finances as bankruptcy proceedings continue.

A spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services said that as the hospital system’s troubles have become public, patients have already started to look elsewhere than Carney for their health care. As a result, of 83 medical beds at Carney, an average of just 13 were occupied in June, they said.

A hearing on the sale of Steward’s other Massachusetts properties previously set for this Wednesday has been rescheduled to August 13, according to court filings.

Congressman Stephen Lynch speaks about Steward Health Care’s bankruptcy outside Carney Hospital in Dorchester, which the embattled company said it shut down. (Libby O’Neill/Boston Herald)