Alzheimer’s study: Boston researchers look at family history’s impact on disease risk

A new Alzheimer’s study by Boston researchers reveals how a person’s family history could be key for identifying people at heightened risk for the progressive disease.

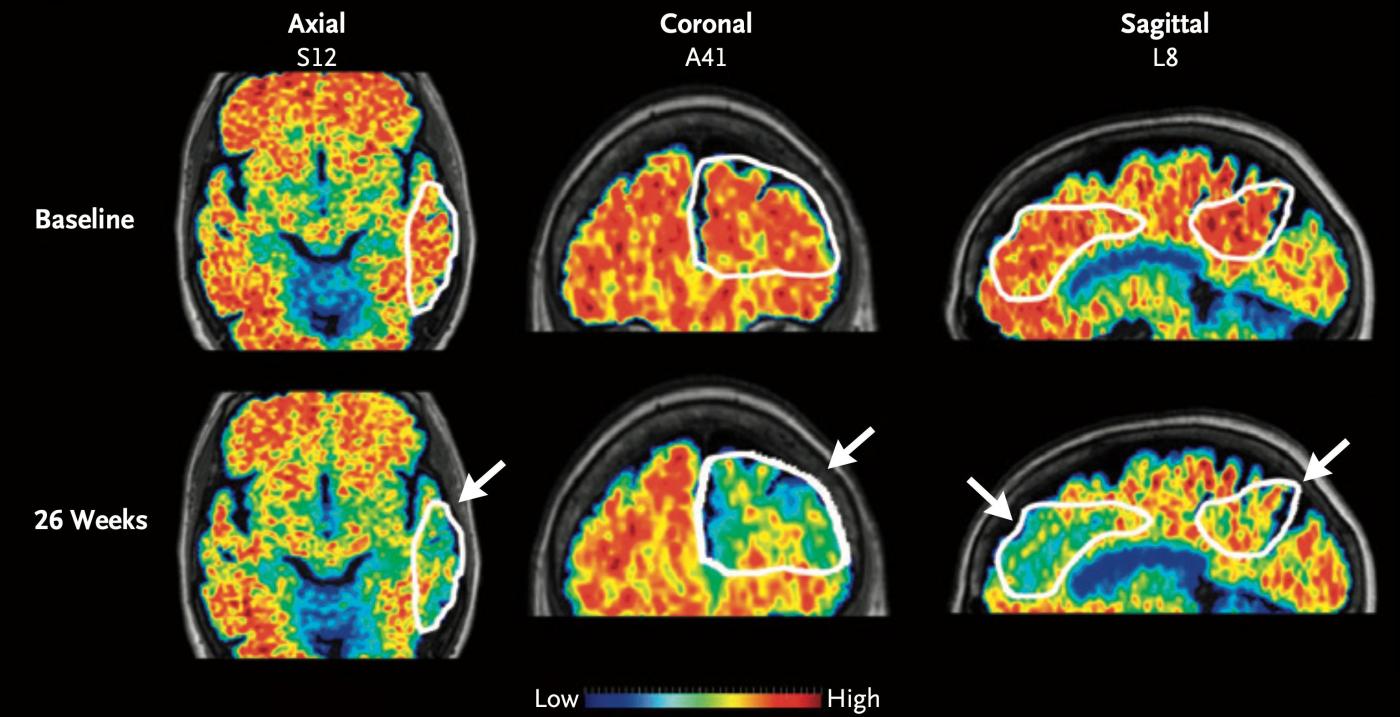

The Mass General Brigham research suggests that a person’s maternal versus paternal family history could have a different impact on the risk of accumulating amyloid in the brain — which is a sign of Alzheimer’s disease.

The scientists looked at 4,400 cognitively unimpaired adults with amyloid imaging, and they found increased amyloid in those who reported that their mothers had symptoms of Alzheimer’s.

“Our study found if participants had a family history on their mother’s side, a higher amyloid level was observed,” said Hyun-Sik Yang, a neurologist at Mass General Brigham and behavioral neurologist in the Division of Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

He said previous smaller studies have investigated the role family history plays in Alzheimer’s, as researchers believe that genetics may play a role in developing the disease.

Some of those studies suggested maternal history represented a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s, but the group wanted to revisit the question with cognitively normal participants and access to a larger clinical trial data set.

The team examined the family history of older adults ages 65 to 85 from the Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s study. Participants were asked about memory loss symptom onset of their parents. Researchers also asked if their parents were ever formally diagnosed, or if there was autopsy confirmation of Alzheimer’s disease.

“Some people decide not to pursue a formal diagnosis and attribute memory loss to age, so we focused on a memory loss and dementia phenotype,” said Yang, who’s also a physician investigator of Neurology for the Mass General Research Institute.

Related Articles

Our brains are growing. Will that help prevent dementia?

Researchers then compared those answers and measured amyloid in participants. They found maternal history of memory impairment at all ages and paternal history of early-onset memory impairment was associated with higher amyloid levels.

Researchers noted that having only a paternal history of late-onset memory impairment was not associated with higher amyloid levels.

“If your father had early onset symptoms, that is associated with elevated levels in the offspring,” said Mabel Seto, a postdoctoral research fellow in the Department of Neurology at the Brigham. “However, it doesn’t matter when your mother started developing symptoms — if she did at all, it’s associated with elevated amyloid.”

She said the results of the study are fascinating because Alzheimer’s tends to be more prevalent in women, adding, “It’s really interesting from a genetic perspective to see one sex contributing something the other sex isn’t.”