John Demma: ‘Is there, in all republics, this inherent and fatal weakness?’

“Age” is a hot issue. Full disclosure: I’m 83. If you stop reading, I understand. Before stopping, perhaps you’ll find this excerpt as enlightening as it is provocative:

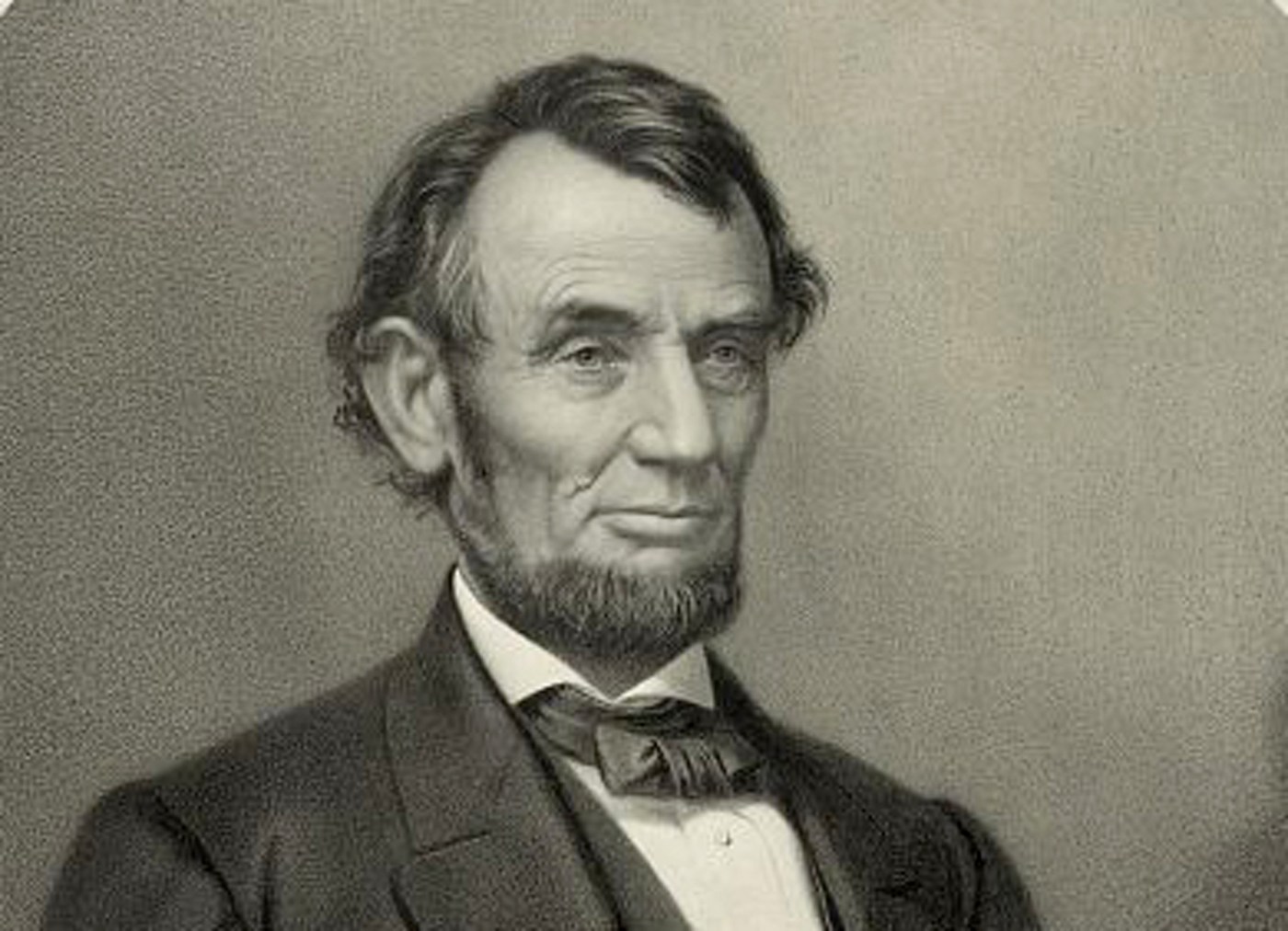

“Is there, in all republics, this inherent and fatal weakness? … Must a government, of necessity, be too strong for the liberties of its own people, or too weak to maintain its own existence?” (President Abraham Lincoln’s July 4, 1861, message to Congress).

Lincoln nails our “fatal weakness” predicament: “government” and our “liberties” are in a stand-off. Law professor and author Noah Feldman dates it back to the nation’s founding:

“The expansion of the United States … posed a fundamental problem for the slavery compromise reached by the framers in Philadelphia. They had done their best to balance the relative power of free and slave states. The fact that all the states then existing had ratified the Constitution showed that their compromise was satisfactory for white voters in their generation … But each time a state was added, it had the potential to change the balance of power between the free and slave states.” (Page 40, “The Broken Constitution”)

Pause and reflect for a moment on the words enshrined in 1776’s Declaration of Independence:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness”.

The Declaration’s glowing “truths” failed severely just a decade or so later at the Constitutional Convention. Enslavers won. Slaves lost, victims of a compromise (and exclusion from “these truths”) accepted by the framers as the cost of a new Constitution ultimately ratified by the states.

Fast forward. To this day many of us are convinced government’s gain in power shrinks our liberty, a zero-sum outcome. That conviction fits Lincoln’s “fatal weakness” of a “too strong” government overwhelming people’s liberty. Consider, too, that many of us are convinced every gain in our liberty is a good thing, especially if our “win” equals a loss or restriction of government’s power. This fits Lincoln’s “fatal weakness” of a government eventually “too weak to maintain its existence” against unrestrained pursuit of life, liberty and happiness.

In a freedom-loving republic (inclusive of all of us, not just some of us) the continually open political questions are: How much government power is too much power? How much liberty is too much liberty?

Lincoln’s “ask” is timeless. Early on, Ben Franklin, (leaving the Constitutional Convention) reportedly answered, “a republic if you can keep it”, to the question, “what kind of government do we have, Mr. Franklin?” “If you can keep it” spotlights every generation’s fundamental job of balancing power and liberty. If We The People (all of us) don’t get the balancing right, we’re sweeping into history’s dustbin the whole idea of self-governance, proving Ben’s warning was spot-on and we’re republic-keeper failures.

Our republic’s inventors handed future generations the power to keep it and, ominously, the liberty to reject it. As some founders aged, they worried the next generation wasn’t up to the job of keeping it. Decades later their early concern was validated when a bunch of states decided they had an “unalienable” right to secede in pursuit of life, liberty and happiness.

Lincoln and 700,000 Civil War battle deaths limited liberty’s reach. Excluded was an “unalienable” right to secede in pursuing life, liberty and happiness. The “Union” prevailed. Assassin John Wilkes Booth took exception. In a rage of passion over reason, he felt his liberty demanded Lincoln’s murder. Lincoln, a few weeks previously, in his second inaugural address, hoping to unify a broken nation, said “with malice toward none with charity for all … let us strive on … to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

For that Lincoln got a bullet in the head as an enraged Booth shouted “sic semper tyrannis” (thus to all tyrants), convinced his “liberty” outranked Lincoln’s right to life. The nation, plodding on, slowly adopted (Historian Shelby Foote notes) the singular form of reference, “United States is”, replacing the plural, “United States are” on its meandering calf path balancing “power” and “liberty” to this day.

In our “Lincoln” moment, we own the republic-keeping job and the balancing work. So, dear readers, how do we propose resolving our frightful predicament? Yes, our republic’s well over two centuries old, which is encouraging but not decisive. For many of us its survival seems tenuous. Key questions demand our enlightened answers:

Will our collective good will and good faith wisely avoid a “fatal weakness” disaster? Or will viral distrust, ill will and bad faith be our master?

Sustaining our self-governance depends on all of us, including you. It’s our path to achieving “life, liberty and happiness” for all of us, not just some of us. We own the judgment our kids, grandkids and great grandkids render. At 83 I tremble at the prospect of my great grandkids asking:

Great Grandpa, your generation’s lives span almost a third of our nation’s existence. On an “A” to “F” scale, how do you grade your generation’s “keeping” of our republic? And why?

John Demma of Eagan is a student of U.S. democracy.