The life and times of Roy Wilkins, a St. Paul native who was a civil rights champion

The tall, lean Minnesotan known for his steady, genteel demeanor collaborated with — and butted heads with — Martin Luther King Jr. and W.E.B. Du Bois, and he earned his share of friends and enemies during 22 years at the helm of the NAACP at the height of the Civil Rights Movement.

Based in New York, the national organization was regarded in its time as the most well-organized Black civil rights group in the country.

It was perhaps ironic, then, that some “Black power” advocates dismissed Roy Wilkins as too soft, bookish and legally-minded, even as he sent attorneys to bail them out of jail after street protests. As early as 1934, he also was arrested.

Despite his many television appearances, he wasn’t a soaring orator like MLK. Yet in his obituary, the New York Times described Wilkins as a chief planner of the legal battle that resulted in the groundbreaking 1954 Supreme Court decision outlawing “separate but equal” public schools — the first domino in a chain of civil rights decisions that reshaped the nation.

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, right, and Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, are seen, Aug. 1963. (AP Photo)

It would be no small feat for the softspoken, high-brow integrationist from St. Paul, to this day overlooked in many a history lesson.

He suffered firsthand the generational and ideological divisions in Black social movements.

“It used to be that picketing, except for a labor cause, was against the law,” a frustrated Wilkins told a reporter in the 1960s. “We went to court over that and won the right for these kids to march and picket now. I understand their impatience. I share it, but they should have some idea what it has taken to get them their right to raise hell.”

Early years in St. Paul

In recognition of Black History Month, it’s worth exploring that topic at greater length.

Wilkins wasn’t exactly a Rice Street kid, having been raised on St. Paul’s Galtier Street, six blocks off the business corridor, in the house his uncle owned after his mother died of tuberculosis in St. Louis. The Rice Street Gang, the “toughest kids in the city” as he would later recall in his autobiography, would throw the N-word around, but they mostly left him alone because he towered over them, tall and lean.

The U.S. Postal Service released a stamp honoring Roy Wilkins, who led the NAACP from 1955-1977, in 2001. The stamp featured a 1940s photograph of Wilkins by Morgan and Marvin Smith. (AP Photo/U.S. Postal Service)

He’d walk the six blocks to hang out with his best friend Herman Anderson, a classmate from Whittier Grammar School, a shy blond kid who spoke to him about a lot of things, but never about the differences in their skin color, at least not until the two of them were in their 70s.

The Swedish woman who lived next door wouldn’t hesitate to slap his backside if she found him misbehaving, but when the two of them got old, he still went to visit her in the nursing home, where they cried together.

“My boy, my boy,” she greeted him, after all those years.

His adoptive mother helped the European immigrants in the neighborhood read their bills. His uncle Sam Williams, his adoptive father, worked 12 hours a day as major domo — a personal attendant and chief porter — to the president of the Northern Pacific Railroad, running the man’s private railroad car across country for weeks at a time when he wasn’t serving him breakfast and dinner, like Alfred at the call of Bruce Wayne.

The job paid uncle Sam enough to afford a house of his own and put a great big turkey on the family table at Thanksgiving, with oysters to boot — and to hire a lawyer to cement Wilkins’ adoption.

NAACP in Minnesota

In the summer of 1913, five years after bloody race riots and horrific lynchings tore apart Springfield, Ill., W.E.B. Du Bois — editor of the Black magazine “The Crisis” — began scouting around St. Paul to launch a chapter of the NAACP. His uncle Sam signed up as a founding member.

Some 800 marchers parade down a Jackson, Miss. street, June 12, 1966 to memorialize the murder of civil rights leader Medgar Evers who was shot in an ambush three years ago. Leading the 20-block pilgrimage are from left, Charles Evers, brother of the victim; John S. Stillman of New York; Roy Wilkins, director of the NAACP and Jackson attorney R. Jess Brown. (AP Photo)

Wilkins, to his aunt’s horror, dismissed church services as “noisy,” yet excelled at math. But the briefest of blurbs in The Crisis one day carried the news that he had been “elected president of the Mechanical Arts High School Literary Society of St. Paul, Minnesota, over two white candidates.” It was unheard of. Excited, Wilkins soon gave up his plans to become an engineer.

When a white girl and her boyfriend accused six traveling circus hands of rape, Duluth police made 13 arrests. A lynch mob composed of thousands of residents stormed the jail and hung three of the Black men from a light pole, stomping on one’s body when the rope broke. The NAACP successfully defended the rest of the “Duluth 13” in a court of law.

Wilkins was 19 and suddenly politicized by the news, which earned him recognition in an oratory competition at the University of Minnesota.

“For the first time in my life I understood what Du Bois had been writing about,” he penned, toward the end of his life. “I found myself thinking of black people as a very vulnerable ‘us’ — and white people as an unpredictable, violent ‘them.’”

Work as a journalist

When he wasn’t the only Black caddy at the St. Paul Town and Country Club, working at the slaughterhouse, waiting tables in a Pullman car or mopping floors at the downtown St. Paul Union Station, he was taking the Rice Street Trolley and the Como-Harriet line each morning to the U of M. He became the first Black reporter for the Minnesota Daily, which, he wrote, “drew me like a bee to clover.”

Once or twice a week, Wilkins earned $3 for putting the paper to bed as night editor.

After college, in December 1922, he became editor of the St. Paul Appeal, which had dwindled to “little more than an advertising throw-away” until he turned it around while also serving as secretary of the St. Paul NAACP, and then the local Urban League.

Elsewhere, Black advocates like Marcus Garvey were talking of building a Black empire and ridiculing Du Bois as too temperate. The feud split Black circles, a precursor of debates that would span the life of the emerging Civil Rights movement and beyond.

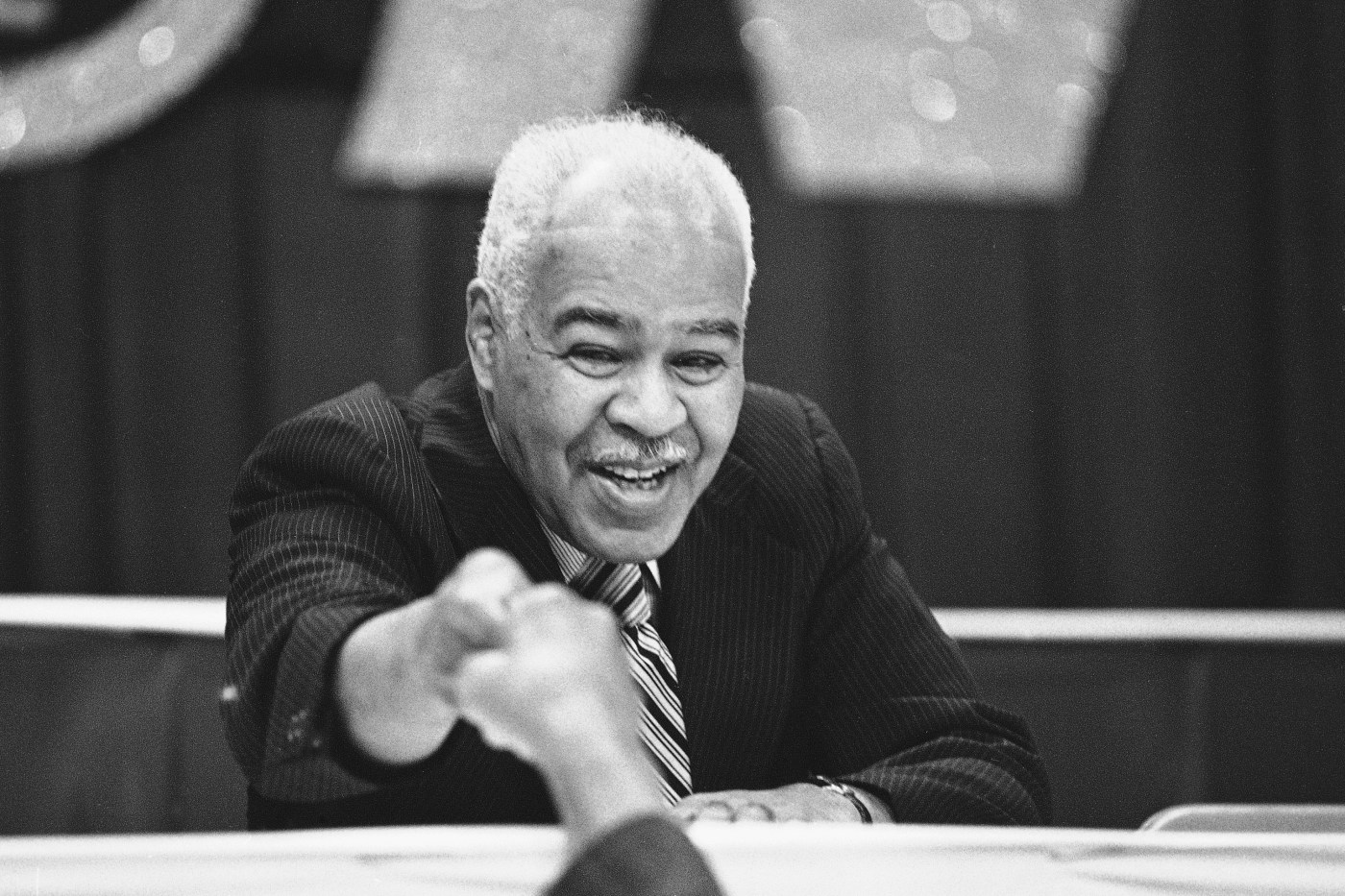

Executive secretary of the NAACP Roy Wilkins testifies before the Senate Government Operations Committee in Washington, Nov. 30, 1966. (AP Photo)

At age 23, Wilkins sided with the 55-year-old Du Bois over Garvey, but then later criticized Du Bois for spending too much time writing about colonialism in Africa instead of lynchings in the United States. When Du Bois eventually turned to what Wilkins called the “voluntary segregation” of separatism and then Communism, Wilkins fumed.

Soon enough Wilkins would get a taste of similar criticism for being focused on integrating Blacks into white society, as opposed to building a Black society independent of whites.

“Years later, Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown and company would cut me much as I had cut Du Bois,” he wrote. “Times change. The souls of young men and old men don’t seem to.”

He joined the staff of the crime-obsessed Kansas City Call, a Black paper, for eight years during the roaring ’20s. More than 60 years before the band Public Enemy would sing “911 is Joke,” Wilkins penned stories urging police to enforce the law in Black neighborhoods and shaming the Linwood Improvement Association for its efforts to “keep black people penned north of 27th Street.”

Segregation

In Minnesota, he’d had brushes with blatant racism and a front seat to disparity. But in Kansas City, everywhere he turned, he found Jim Crow laws — legally-enforced segregation.

In 1930, at his urging, the paper called out Hoover’s nomination of a potential Supreme Court justice who had once said “the participation of the Negro in politics is a source of evil and danger to both races.”

Roy Wilkins, left, executive secretary of the NAACP, and Medgar Evers, center, field secretary of the NAACP are arrested for picketing, June. 1, 1963 in downtown Jackson, Mississippi. (AP Photo/Jim Bourdier)

The Supreme Court nominee lost his confirmation battle, and the young Wilkins was soon offered a position by Du Bois as business manager of The Crisis in New York City. He turned it down, only to later be hired as assistant secretary of the NAACP, where he found himself assigned to help keep The Crisis afloat during the Great Depression.

Before Du Bois resigned in a huff from the magazine he founded, he attempted without success to get rid of Wilkins, among others.

”In office politics, blacks can be just as rough as whites,” Wilkins wrote.

An undercover assignment led to his groundbreaking 1932 report on poor wages and horrific working conditions for Blacks in Mississippi’s U.S. Army Corps levee labor camps, spurring Congressional action and raises for hundreds of workers.

Brown v. Board of Education, Civil Rights

Then came the the years of legal fights that thrust the NAACP — and its top attorney, Thurgood Marshall, a future Supreme Court justice — into the thick of the civil rights era. Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 Supreme Court decision that overturned “separate but equal” as a legal basis for school segregation, was like winning “a second Emancipation Proclamation,” Wilkins would later write, referring to Abraham Lincoln’s Civil War-era proclamation against slavery.

With Wilkins elevated to the helm of the NAACP in 1955, the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and Fair Housing Act of 1968 would follow.

A group which arrived at Washington’s National Airport, Aug. 27, 1963, to participate in tomorrow’s massive March On Washington civil rights demonstration at the nation’s capital. From left: opera singer Marian Anderson; Roy Wilkins, executive secretary of the NAACP; actor Paul Newman; Rev. Robert Spike of the National Council of Churches in New York City; and actress Faye Emerson. (AP Photo/William J. Smith)

Wilkins noted that the famed Montgomery bus boycotts had succeeded because Rosa Parks did not stand alone — an entire city full of Black workers organized by Black church leaders, led by MLK, were there to boycott the bus company with her, ultimately drawing a Supreme Court decision in their favor. In San Francisco, which lacked the same critical mass, a taxi boycott fizzled.

Over the years, five U.S. presidents — including John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson — turned to Wilkins for advice on sensitive racial matters, and he sometimes lambasted them for failing to deliver. National leaders dragged their feet on federal anti-lynching legislation, worried it would cost them votes on other bills down south. Wilkins and MLK, a close confidante, disagreed over whether to link the anti-Vietnam War movement to civil rights efforts, a strategy Wilkins disliked.

When Black nationalists made “Black power!” a rallying cry, Wilkins rejected it as separatism, another mindset he saw as self-defeating. He chafed as sit-ins in the south drew more attention than the NAACP’s New York-based legal work through the courts. There were those within the organization who sought to unseat him.

Still, between the time he joined its inner circle in the early ‘30s and when he retired after 22 years as director in 1977, the NAACP had grown from 25,000 members to 400,000, from 690 branches to 1,700, and from a budget of $80,000 to $3.6 million, according to his obituary in the New York Times.

The Roy Wilkins Memorial, seen Sept. 26, 2017 on the grounds of the Minnesota State Capitol in St. Paul, was created by sculptor Curtis Patterson and dedicated on November of 1995. The 46 central elements in the sculpture, “Spiral for Justice,” represent the 46 years of Roy Wilkins’ leadership of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in its fight for social and economic justice for all Americans. (Scott Takushi / Pioneer Press)

When he died in 1981, at the age of 80, President Ronald Reagan said Wilkins “worked for equality, spoke for freedom and marched for justice. His quiet and unassuming manner masked his tremendous passion for civil and human rights. … The accomplishments of his life will continue to endure and shine forth.”

An elementary school near his longtime home in Queens, N.Y., carries his name, as does a Parks and Rec center there. In 1985, the old St. Paul Auditorium at the downtown St. Paul RiverCentre was renamed in his honor. In 2021, the St. Paul City Council swapped in his name for Lewis Park, the Marion Street green that once bordered his uncle’s house, which was demolished in the ’70s.

Why eulogize him now? A few weeks ago, when the Twin Cities chapter of the Communication Workers of America planned an online discussion at noon on Thursday about Wilkins with University of St. Thomas professor Uhuru Williams for Black History Month.

To join the event register for the discussion Roy Wilkins: Minnesota Journalist to Civil Rights Luminary at Zoom.

Related Articles

3M spinoff Solventum to be listed on NYSE as SOLV

Teen shot in St. Paul dies, 17-year-old shooter charged

Metro Transit bus driver fatally strikes pedestrian in St. Paul’s Highland Park

Muneer Karcher-Ramos, founding director of St. Paul Office of Financial Empowerment, to move on

St. Paul’s West 7th St. resurfacing project public meeting to be held March 6