China’s Rise – (Part 1) Internal Struggle

By: Stewart Brennan

“It is said that if you know your enemies and know yourself, you will not be imperiled in a hundred battles. If you do not know your enemies but do know yourself, you will win one and lose one. If you do not know your enemies nor yourself, you will be imperiled in every single battle.” ~ Sun Tzu [01]

Behind the wall of western hubris and propaganda on China, there remains 5,000 years of experience in war, politics and economics. These disciplines, embedded within Chinese culture, have never disappeared from thought in those that have led China for thousands of years, regardless of politic that led the country in the past or present; be it a Republican Democracy, Communist State, National Socialist State or Royal Imperial State.

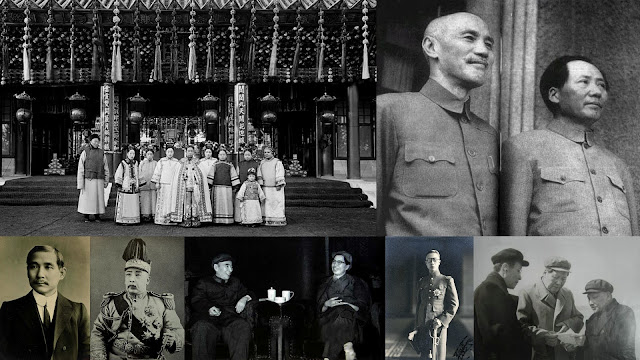

It is my view that the many years of Chinese political and cultural history did not suddenly disappear overnight when China’s governing structure changed to communism. The last Royal Chinese Imperial Dynasty [02] (Qing) had only just ended (1912) with the Xinhai Revolution [03] and so thousands of years of Chinese evolution doesn’t just suddenly disappear in a generation.

In reality, routines become a way of life after long periods of time and then become culture that the people of the society identify with as a normal way of doing things. Over time, everything becomes refined, pleasantries, planning, transactions, understanding, economics, politics, war; and so, Mao Zedong’s [04] China must be viewed and perceived with the retention of a large part of their culture intact with set ways of doing things where a supreme ruler would wield his political power much the same way as a past Chinese emperor, while the political courts and people surrounding him would also be conditioned in the disciplines and ways of doing things from the past.

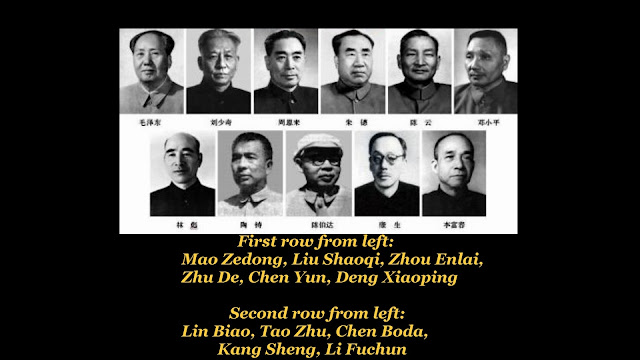

What many people in the west are not aware of during China’s communist rule is that there were actually many factions within the Chinese governing structure with differing thoughts and plans for China’s economic future who were fighting with each other for power. The two main rivals that survived were the hardline Soviet style communists and a Nationalist Socialist group that leaned towards a more capitalist approach in their political economic vision of the country.

It’s difficult to understand what took place during that time in China (1949 to 1979) if we do not read history and only view it from a minimalist western perspective. It can be better understood if we equate the two surviving Chinese factions within the Communist party to the two super powers that emerged at the end of World War II in complete opposition to one another. (Capitalist USA and Soviet Russia) However, it is more realistic to understand this period of history if we compare it hypothetically, to a more traditional Chinese period by likening Chairman Mao to an emperor of their past who had competing heirs to the throne that engaged in a fierce political battle with one another to prove their ideas, worth and devotion to the father; a father who must ultimately choose which son’s plan would make his Imperial rule a favorable and lasting one for the country.

Before Chinese communist rule took hold as the governing entity in 1949, China went from a 5,000-year old Imperial Monarchy, which had its own periods of domestic wars and internal violence, to a country that was broken by wars of foreign intervention beginning with the First Sino Japanese war in 1894-1895 [05], which led to the Boxer Rebellion 1899-1901 [06] and ultimately to the Xinhai Revolution in 1911. The result of those two foreign wars shattered the country and turned it into a Western style Republican Democracy [07] by 1912.

The fall of China began with their loss to Japan in the first Sino-Japanese war from July 25th, 1894 to April 17th, 1895. The Chinese ruling Qing dynasty under Empress Dowager Cixi [08] was ill prepared against the more advanced Imperial Japanese military. The loss showed weakness and signaled the end of the Qing empires domination of Asia, while the humiliation of losing Korea as a tributary state to Japan as a consequence, sparked an unprecedented public outcry that became a catalyst for a series of political upheavals led by Sun Yat-sen [09] and Kang Youwei, [10] culminating in the 1911 Xinhai Revolution.

The growth of foreign spheres of influence in China after the Sino-Japanese War of 1895 led directly to the “Boxer Rebellion” (1899 to 1901) between the Qing Empire of China and an Eight-Nation Alliance that included Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, United Kingdom, Italy, Japan, Russia, and the United States which also included Belgium, Spain, and the Netherlands. China’s defeat was another humiliating blow [11] to the Qing Dynasty and to the people of China.

In China’s past, if weakness was shown by the ruling family, it created internal division and a challenge by wealthy groups against those who ruled the Chinese empire; and so, those two major losses broke China and caused division in the decision on how to strengthen the country and move forward. During this period of time, China was ruled by the iron fist of Empress dowager Cixi from 1861 until her death in 1908.

Empress Dowager Cixi (1903)

Empress Dowager Cixi (1835 – 1908)

However, with the sudden death of her heirless 19 year old son from small pox in 1875, Cixi consolidated control over the dynasty by installing her three year old nephew as the Guangxu Emperor, contrary to the Qing dynasty rules that had been in place since 1644. In essence, Cixi ruled China and did what ever she needed to retain power which had been declining due to foreign economic interference.

Cixi supervised a series of moderate reforms that helped the regime survive until 1911. Although Cixi refused to adopt Western models of government, she supported technological and military reforms with a Self-Strengthening Movement as a means of limiting Westernization to preserve her own power and the dynasty.

China made substantial progress toward modernizing its heavy industry and military through the 1880’s and 1890’s but the majority of the ruling elite still subscribed to a conservative Confucian worldview, and the “self-strengtheners” were by and large uninterested in social reform beyond the scope of economic and military modernization. The Self-Strengthening Movement (1861 to 1895) under Cixi succeeded in securing the revival of the dynasty from the brink of eradication, sustaining it for a half-century, however the considerable successes of the movement came to an abrupt end with China’s defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895.

The purge of China’s cultural history began by the loss of “Korea” as a tributary state in the First Sino Japanese war and the outrageous indemnities China had to pay the eight victorious foreign nations from the “Boxer Rebellion” war. China’s history and independence began falling faster to foreign economic influence.

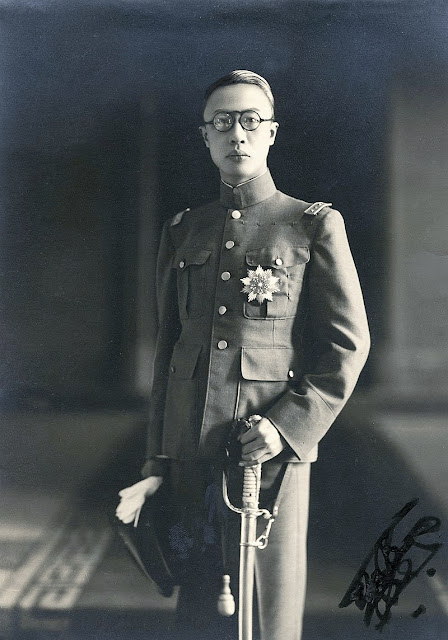

The “Xinhai revolution” which followed, consisted of many revolts and uprisings, however, the turning point was the Wuchang Uprising [12] on 10 October 1911, when people rose up in opposition against the Qing governments decree to nationalize local railway development and transfer control to foreign banks. The movement, expressed mass discontent with Qing rule and galvanized the revolution against them. The revolution ended with the abdication of the last Chinese emperor, the six-year-old Puyi [13], on February 12th, 1912, and marked the end of 5,000 years of imperial rule and the beginning of China’s early republican era.

The Republic of China was declared on January 1st, 1912. Shortly after, the country descended into a melee of power grabs and coup attempts.

Sun Yat-sen, the founder and president of the new Republic served briefly before handing over his position to Yuan Shikai,[14] the leader of the Beiyang Army [15]. Sun Tar-sen’s party, the Kuomintang [16] (KMT), then led by Song Jiaoren, won the parliamentary election held in December 1912. However, Yuan Shikai, the Beiyang Army leader seized control of the government, and assassinated Song Jiaoren. In 1915, Yuan Shikai proclaimed himself Emperor of China but abdicated shortly afterwards due to popular unrest.

After Yuan’s death in 1916, the authority of the Beiyang government was further weakened by a brief restoration of the Qing dynasty. Cliques in the Beiyang Army claimed individual autonomy and clashed with each other during the ensuing Warlord Era [17] (1916 to 1928).

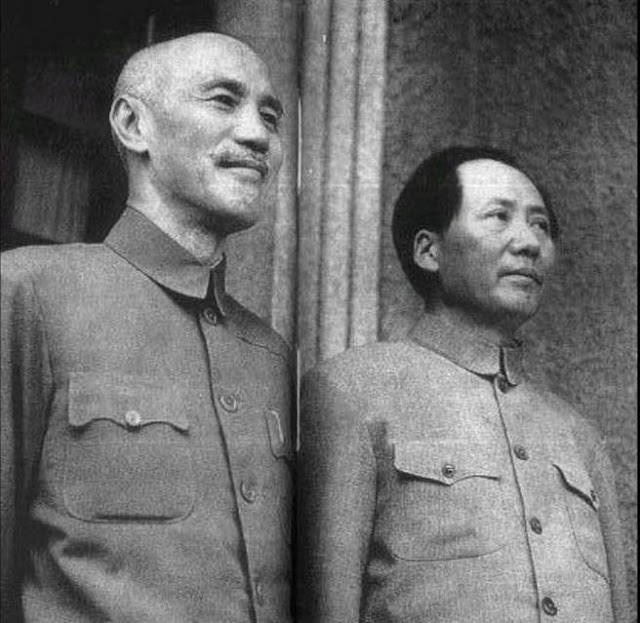

By 1921, the KMT established the national government in Guangzhou, supported by the fledgling Communist Party of China (CPC). The economy of Northern China, which was overtaxed to support warlord adventurism, collapsed between 1927 and 1928. General Chiang Kai-shek [18], who became the Chairman of the Kuomintang after Sun Yat-sen’s death in 1925, started a Northern Expedition in 1926 to overthrow the Beiyang government, which was accomplished two years later in 1928. However, in April 1927, Chiang Kai-shek established a nationalist government in Nanjing and massacred Communists in Shanghai. The latter event forced the Communist Party of China into armed rebellion, marking the beginning of the Chinese Civil War [19].

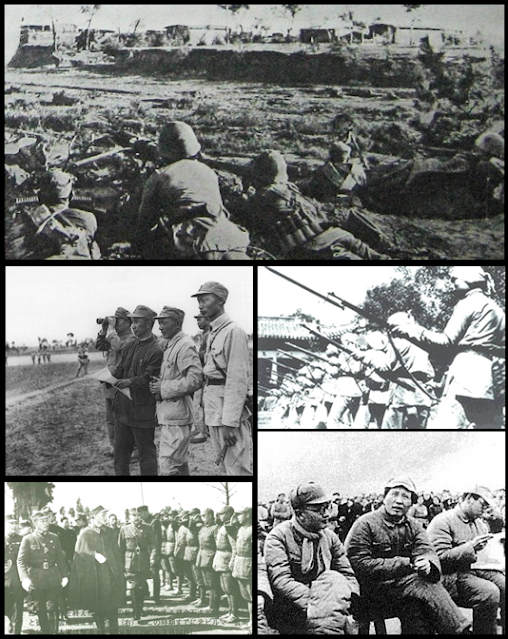

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang (KMT)-led government of the Republic of China (ROC) and the Communist Party of China [20] (CPC) lasting intermittently between 1927 and 1949. The war is generally divided into two phases with an interlude: from August 1927 to 1937, the KMT-CPC Alliance collapsed during the Northern Expedition, while the Nationalists controlled most of China. However, from 1937 to 1945, hostilities were put on hold, and the Second United Front between the two groups joined forces and fought the Japanese invasion of China with eventual help from the Allied forces of World War II. The civil war resumed after the Japanese defeat, where the CPC gained the upper hand in the final phase of the war from 1945 to 1949, generally referred to as the Chinese Communist Revolution.

The Communists gained control of mainland China and established the People’s Republic of China [21] (PRC) in 1949, forcing the leadership of the Republic of China to retreat to the island of Taiwan. A lasting political and military standoff between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait ensued, with the ROC in Taiwan and the PRC in mainland China both officially claiming to be the legitimate government of all China. No armistice or peace treaty has ever been signed, which has raised the question of whether this war itself has legally ended, or temporarily halted.

During this very turbulent time, (1894 to 1949) the people of China found themselves caught in the middle of an economic war between the upper classes of China, Japan, Europe and the United States.

For years the common people of China were brutalized by European and Japanese occupation but also by groups within China some of whom collaborated with the foreigners. Anger, resistance and determination against the occupation forces culminated into a popular revolution to cast off the shackles of foreign Imperialism and push forward to regain their national, cultural and economic independence.

China had emerged at the end of the second world war in 1945 economically weak and on the verge of all-out civil war. Large swathes of the prime farming areas had been ravaged and there was starvation. Many towns and cities were destroyed, while millions were rendered homeless by floods. The problems of rebuilding China after a long-protracted war were staggering, which left the Nationalists severely weakened.

Meanwhile, the war strengthened the Communists both in popularity and as a viable fighting force. In the communist controlled areas, Mao Zedong the leader of the communist forces was able to adapt Marxism–Leninism to Chinese conditions.

Mao also began to execute his plan to establish a new China by rapidly moving his forces from across the country to Manchuria. The Soviet occupation of Manchuria, although short, was long enough to allow the Communist forces to move in and take all the military hardware surrendered by the Imperial Japanese Army, which allowed them to quickly establish control in the countryside and move into position to encircle the Nationalist government armies in the major cities of northeast China. Following that, the Chinese Civil War broke out between the Nationalists and Communists, which concluded with the Communist victory in mainland China and the retreat of the Nationalists to Taiwan in 1949.

The years leading up to China’s re-established independence through a communist victory in 1949 put an end to foreign domination and domestic infighting that had torn the country apart for 55 years.

With the fall of Japan in 1945, and thus Manchukuo where the Japanese installed Puyi as their puppet Emperor of China, Puyi fled the capital and was eventually captured by the USSR. The War Crimes Trials of the Far East in 1946 [22] saw Puyi imprisoned for ten years as a war criminal. He was extradited to the People’s Republic of China in 1949 after Communist Rule had been established. However, in China, he was not executed, as Mao Zedong reasoned that Puyi was more valuable as a reformed commoner than a murdered emperor. After his reform, Puyi became a member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference [23] and the National People’s Congress [24] a political body which advised the hierarchy of the Communist government. Puyi died in 1967 during the Cultural Revolution, and was ultimately buried near the Western Qing tombs in a commercial cemetery.

So, looking at this period of history (1958 to 1979) we must compare it with the Imperial China of the past where fierce political battles were waged between would be heirs to the throne for the right to lead the nation unopposed, where the Imperial court is dragged into a vicious political battle by all sides.

The battle of China’s rival sons within the Communist party came to a head during the, “Cultural Revolution” [25] (1966 to 1976), where the ideas of Mao and the first son (hardline communism) were put into action, which was to reimpose order from the chaos and aftermath of the Mao Nationalist Socialist project called the “Great Leap Forward” [26] (1958 to 1962).

The Cultural Revolution marked China’s return to a more rigid position of power after a five-year period of economic failure from the “The Great Leap Forward”. The official reasons of the program’s failure were attributed to 30% natural disasters and 70% manmade errors.

It is important to point out during the five-year Great Leap Forward plan, that there was also a three-year political purge across China from 1959 to 1961 by hardline communist elements through their “Anti-Rightist Campaign” [27] that saw the end of all political / economic opposition while turning the country into a hardline one-party system. The disruptive nature of the “Anti-Rightist Campaign” greatly impeded the economic flow within China and was one of the major factors in contributing to the failure of “The Great Leap Forward” and one of the worst famines in recorded human history [28] where between 30 to 55 million people died of starvation. Exact numbers are not known.

Also, interesting to note, is that after the 1959 “Lushan Conference” [29], Chairman Mao stepped down as the State Chairman of the PRC (Peoples Republic of China) due to the ongoing failures of “The Great Leap Forward” but remained Chairman of the CCP and appointed “Liu Shaoqi” [30] (the new PRC Chairman) and reformist Deng Xiaoping [31] (CCP General Secretary) both National Socialists in charge to change policy and bring economic recovery. Also, of note is the purge of Defence Minister, Marshal “Peng Dehuai” [32], whose criticism of some aspects of the Great Leap Forward was seen as an attack on the political line of Chairman Mao. He was replaced by military hardliner, “Lin Biao” [33] who led the three-year political purge across China.

After the disaster of the Great Leap Forward, Mao felt China needed solutions to counter the turmoil, chaos and division raging across a country that could potentially rise up against the government and Mao himself. China was moving in a very dangerous direction, and so Chairman Mao made the decision to try a more hardline approach and returned to lead the country through, “The Cultural Revolution” in 1966.

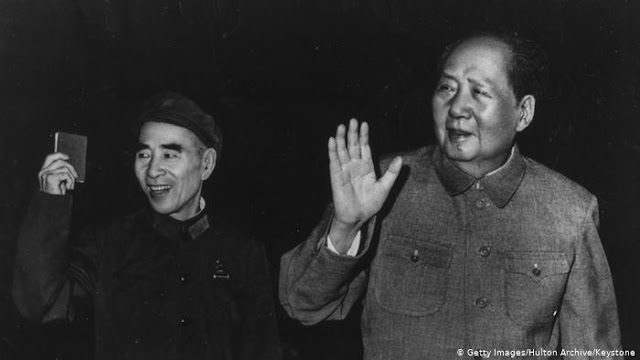

In essence, Mao called on the nation’s youth to clean up the “impure” elements of Chinese society and revive the revolutionary spirit that had led to victory in China’s civil war two decades earlier that led to the formation of the People’s Republic of China. The hardliners embraced it and called it” Mao Zedong Thought” or “Maoism”,[34] and pushed it as the dominant ideology in the “Communist Party of China” (CPC).

Historical Inflection

What is missing in history books here is the consultation Mao had with the different groups within the party including his fourth wife Jiang Qing, so I’ll use the historical parallel of China’s previous dynasties as an example to clarify the decision process.

The decisions of an emperor are always made with great planning and thought when finally presented to the people. It comes to the public as an emperor’s decision, but in reality, the plan is usually partly owned by the emperor and the rest by those who are close to him or influence him towards his decision.

Before coming to a conclusion, there is harsh political dialog behind the scenes by competing rivals (heirs to the throne) which often included the influence of the different mothers of those heirs. (“Mothers” meaning, the different wives of the emperor.) In these fierce, sometimes violent drawn-out contests, there were plots and sabotages made on each other to undermine the rival’s political appearance to the emperor, while promoting the points of their political positions, ideologies and economic interests and why their plan was good for the country. The side that does not prove its point to the emperor, must humble themselves in complete submission and face its demise or humiliation. Sometimes, if allowed to live, they slowly find their way back from obscurity and calculate a different angle to make their plan work.

If a group fails in its tasks of carrying out their Emperors plan, which was made public as the Emperors plan, they are severely reprimanded, imprisoned or executed, while their subordinates in general are either purged or demoted; most of whom would quietly continue to pledge their honor and loyalty to those they served. The victorious group is given permission by the Emperor to carry out a new detailed plan in the emperor’s name including a public announcement.

Since the failure of the “Great leap Forward” (1958-1962) was a disaster under the national socialist tenure, Mao severely disciplined the group and made them responsible for his failure, including President Liu Shaoqi and General Secretary Deng Xiaoping.

So, Mao moved forward with the hardline communists for the chance to restore his honor by endorsing the “Proletarian Cultural Revolution” to go ahead under his leadership which included Lin Biao, and Mao’s fourth wife, Jiang Qing [35] both of whom had great influence in putting it together. (In hind sight, one could draw parallels of Jiang Qing to the dowager empress Cixi of the Qing Dynasty, but perhaps a little more sinister.)

Mao launched “The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution” in August 1966, at a Central Committee Plenary Meeting. He closed public schools, calling for the mobilization of young people to take party leadership and to face the bondage of bourgeois values and those with a lack of revolutionary zeal.

In the following months, the movement increased rapidly as students formed a paramilitary group called the Red Guards [36a] and attacked and harassed Chinese intellectual groups.

The Cultural Revolution, was overtly pro-Maoist, and gave Mao and the hardliners the power and influence to purge the Party of his political enemies at the highest levels of government. Along with closing China’s schools and universities, it encouraged Chinese youth to destroy old buildings, temples, and art, while attacking their “revisionist” teachers, school administrators, party leaders, and parents. (See Here [36b])

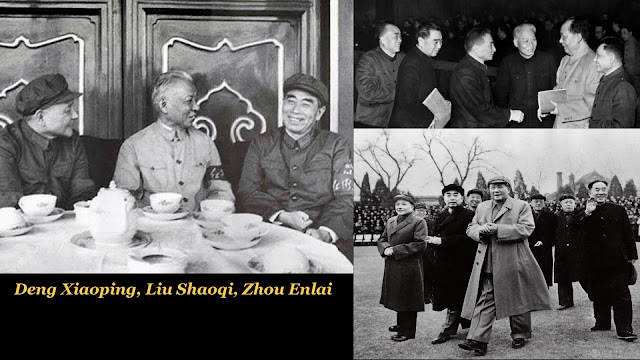

Many of the most senior members of the CCP who had shared Zhou’s hesitation in following Mao’s direction, including President Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, were removed from their posts almost immediately. They, along with their families, were subjected to mass criticism and humiliation.

Deng Xioping and his family were targeted by Red Guards, who imprisoned Deng’s eldest son, Deng Pufang who was tortured and was thrown out of a four-story building window in 1968, becoming a paraplegic. In October 1969 Deng Xiaoping was sent to the Xinjian County Tractor Factory in rural Jiangxi province to work as a regular worker. He was purged nationally, but to a lesser scale than President Liu Shaoqi.

Liu Shaoqi disappeared from public life in 1968 and was labelled by the hardliners as the “commander of China’s bourgeoisie headquarters”, China’s foremost “capitalist-roader”, and a traitor to the revolution. He died under harsh treatment while in prison in 1969.

Although Zhou escaped being directly persecuted, he was not able to save many of those closest to him from having their lives destroyed by the Cultural Revolution. Sun Weishi, Zhou’s adopted daughter, died in 1968 after seven months of torture, imprisonment and rape by Maoist Red Guards. In 1968, Jiang Qing also had Zhou‘s adopted son (Sun Yang) tortured and murdered by Red Guards.

With different factions of the Red Guard movement fighting against perceived threats, many cities in China reached the brink of unrest in September 1967, when Lin Biao sent the army to restore order. Amid the turmoil, the Chinese economy plummeted, with a loss of industrial production in 1968 by 12 percent below the 1966 level. The army immediately forced many members of the urban Red Guard into rural areas to learn farming, where the movement then declined.

In 1969, Lin Biao managed to take power officially as Mao’s successor. He immediately used an excuse of clashes with Soviet troops at the border to form a state of martial law. Disturbed by the destructive force of Lin Biao, Mao turned to his trusted friend Zhou Enlai [37], the Premier of the Peoples Republic of China, for solutions.

China not only needed to pull itself out of economic disaster and internal conflict, Mao now had to find a way to dismantle the challenge to his position by the hardliners who had continued to divide the country through their fist of violence, imprisonment, torture and executions. Everything the revolution had achieved was in jeopardy, so Mao turned to his closest friends with Nationalist Socialist leanings and put them into action. Internal economic success would require an outside ally, and so a reply to US inquiries to seek a meeting with the Chinese government were answered by Zhou Enlai in December 1970 and relayed back through foreign diplomatic channels in Pakistan to the USA that China was indeed interested in the US request for diplomatic communication. The Chinese communication stated that “the US initiative had the support of Chairman Mao and Vice Chairman Lin Biao”.

On July 08th, 1971, after several secretive diplomatic communications, Henri Kissinger visits China in Secret. (see here[38a] and here [38b])

In his meeting with Zhou Enlai at the “Great Hall of the People” on July 10th, many topics were discussed including commitments on Taiwan by Henri Kissinger [39] including the withdrawal of two-third of the US forces present on the Island, a huge point of contention for Chairman Mao which would serve as a positive reason while eliminating suspicion from the hardliners for the sudden meeting with the leader of the Capitalist world.

Important to note is that Zhou Enlai let Kissinger know, in answer to questions previously submitted by the US for discussion, that China was looking to indeed develop their economy, although it would take a while, but they would try to go all out, aim high, and develop their “socialist construction” in a better, faster, and in a more economical way. Zhou continued, saying the second part of their answer was that once their economy was developed, they would still not consider themselves a superpower and would not join the ranks of the superpowers.

The meeting between Vice Chairman Zhou Enlai and Henri Kissinger came at a very critical time in China’s internal struggle which then set off a series of events that would strengthen the Socialists position within China. It was a stroke of political mastery by Chairman Mao and Zhou Enlai over the hardliners who had sowed chaos throughout the country and the subsequent loss of support by the people.

Strange and significant events in the USA and China seemed almost coordinated at times, yet cautious in a Yin Yang trust building partnership leading up to the historic meeting of US President Richard Nixon and Chairman Mao Zedong of China in February 1972.

Important Events in the US & China after Kissinger’s meeting with Zhou Enlai

On August 15th, 1971, after meeting with “Federal Reserve Chairman” Paul Volker, in a major economic shift from world war II, Nixon cancelled Bretton Woods by announcing actions to suspend, with certain exceptions, the convertibility of the US dollar into gold or other reserve assets, and ordered the gold window to be closed such that foreign governments could no longer exchange their dollars for gold.

On Sept 13th, 1971, Lin Biao leader of the hardline communist faction in China, died in a mysterious plane crash in Mongolia, apparently while trying to flee to the Soviet Union. But before the crash, Mao Zedong had taken measures to distance himself from Lin Biao in August 1971 after personally inspecting troops in central and southern China while stating publicly his differences with Lin Biao.

After the plane crash, members of Lin Biao’s military high command were then cleansed. The four military cadres in the Politburo, Huang Yongsheng, Wu Faxian, Li Zuopeng, and Qiu Huizuo were arrested and not released until the late 1980’s.

Zhou Enlai then took control of the government.

Around the time of the death of Lin Biao in 1971, the Cultural Revolution began to lose momentum. The new commanders of the People’s Liberation Army demanded that order be restored in light of the dangerous situation along the border with the Soviet Union.

On Oct 25th, 1971, China became one of the five Permanent members of the UN Security Council [40] with full veto powers, replacing Taiwan.

1972 Feb 17 – Nixon Goes to China [41]

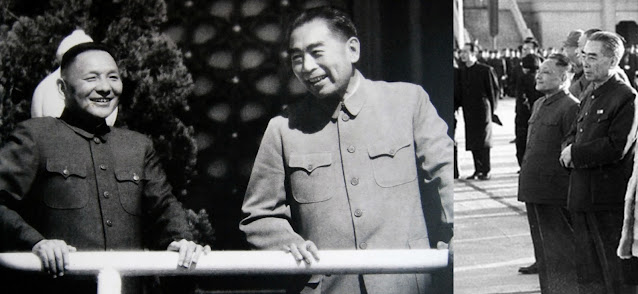

As Mao’s health began to decline in 1971 and 1972 and following the death of disgraced Lin Biao, Zhou Enlai was elected to the vacant position of First Vice Chairman of the Communist Party by the 10th Central Committee in August, 1973 and thereby designated as Mao’s successor (the third person to be so designated after Liu Shaoqi and Lin Biao) Premier Zhou Enlai, who had accepted the Cultural Revolution, but never fully supported it, regained his authority, and used it to bring National Socialist Deng Xiaoping [42] back into the Party leadership at the 10th Party Congress. Deng Xiaoping, who had been purged early on in the Cultural Revolution, took effective control of the government as Zhou became more ill.

Deng focused on reconstructing the country’s economy and stressed unity as the first step by raising production. He remained careful, however, to avoid contradicting hardline ideology on paper, but his internal struggle with the hardliners, led by “The Gang of Four” [43], continued over the leadership of China.

“The Gang of Four” were Jiang Qing (Mao Zedong’s last wife), Zhang Chunqiao, Yao Wenyuan, and Wang Hongwen.

Important to note that at the end of 1973, Mao Zedong began to rely on Deng Xiaoping to handle US-China relations, he also turned to Deng Xiaoping to help him strengthen his control of the army.

1973 (July) was also the year that the Trilateral Commission [44] was Created by the Western Economic cartel (Bankers from the USA, the Western Europe nations and Japan). The Trilateral Commission was formed to bring about substantive political and economic partnerships across the world while focusing on the developing nations with a greater improvement of East-West relations. ie: China. Many of these same nations had participated in the destruction of Imperial China with sights on its economics 70 years earlier. Later that year in October 1973, Henri Kissinger met Chinese officials in Beijing [45].

Deng Xiaoping (who had been political commissar of the 2nd Field Army during the civil war) became the most influential of the remaining army leaders. When Premier Zhou Enlai fell ill with cancer, Deng became Zhou’s choice as successor, meaning that he could have, in theory, also have succeeded Mao.

During the next several years, a protracted factional struggle took place between the hardline Gang of Four and the National Socialists led by Zhou and Deng.

Zhou Enlai’s last major public appearance was at the first meeting of the 4th National People’s Congress on 13 January 1975, where he presented the government work report.

The hardline Communist Gang of Four saw Nationalist Socialist Deng Xiaoping as their greatest challenge to power. In order to keep internal peace, Chairman Mao asked Deng to draw up a series of self-criticisms. Although Deng admitted to having taken an “inappropriate ideological perspective” while dealing with state and party affairs, he was reluctant to admit that his policies were wrong in essence. His antagonism with the Gang of Four became increasingly clear, and Mao seemed to sway in the Gang’s favour. Mao refused to accept Deng’s self-criticisms and asked the party’s Central Committee to “discuss Deng’s mistakes thoroughly”.

Zhou Enlai had fallen out of the public eye after the National Peoples Congress meeting in January 1975 for medical treatment and died of bladder cancer a year later in January 1976.

Zhou was a very important figure in Deng Xiaoping’s political life, and so his death left Deng alone within the Party’s Central Committee. After Deng delivered Zhou Enlai’s official eulogy at the state funeral, the Gang of Four, with Mao’s permission, began to criticize Deng.

The massive public outpouring of grief which Zhou Enlai’s death provoked in Beijing turned to anger at the Gang of Four, leading to the 1976 Tiananmen Incident.[46]

The Tiananmen Incident was a mass gathering and protest on 5 April 1976 Tiananmen Square in Beijing held on the traditional holiday and day of mourning called the Qingming Festival. [47] The Gang of Four branded the event as counter-revolutionary and threatening to their power and blamed Deng Xiaoping as the mastermind behind the incident.

During the Tiananmen Incident, thousands of people protested the militia’s removal of wreaths honoring Zhou Enlai in front of the Monument to the People’s Heroes. Vehicles were burned, offices ransacked and there were reports of many injuries.

Mao himself wrote that “the nature of things has changed”. This prompted Mao to remove Deng from all leadership positions, although he retained his party membership, which indicates that Deng was still under Mao’s protection.

In the aftermath on April 06th, 1976 Premier Hua Guofeng [48] was appointed to Deng’s position as Vice Chairman and the vacant position of “First Vice Chairman”, which Zhou Enlai had once held. The appointment of First Vice Chair made “Hua Guofeng”, Chairman Mao’s fourth official successor.

The Gang of Four’s attempts to suppress public displays of grief resulted in demonstrations against the Gang of Four and Mao himself. However, five months later, chairman Mao, China’s leader for 27 years, died on September 09th, 1976. The entire country entered an extended period of mourning.

Mao was revered by the people of China much the same way a great Chinese Emperor’s had been in the past. For all the major problems that China experienced under Mao’s tenure, he was still revered and held blameless. The hardships that the people faced were blamed instead on those that advised him. Mao was 82 when he died.

Hua Guofeng who now held the three most powerful positions in the Chinese government, arrested the Gang of Four and denounced them as “counter-revolutionary”. Of special note, Hua Guofeng also served on Zhou Enlai’s committee to investigate, Lin Biao in 1971.

The Gang of Four, together with general Lin Biao who had died in 1971, were labeled the two major “counter-revolutionary forces” of the “Cultural Revolution” and officially blamed by the Chinese government for the worst excesses of the societal chaos that ensued during the ten years of turmoil it brought. Their downfall on October 6, 1976, a mere month after Mao’s death, brought about major celebrations on the streets of Beijing and marked the end of a turbulent political era in China. The hardline Communists had been defeated.

Although Hua Guofeng was the First Vice Chairman and designated successor to chairman Mao, it must be noted that Hua Guofeng was one of the survivors of the “Long March” [49] along with Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, Lin Shaoqi, and Deng Xioping. All of whom became very close with unending loyalty and support for each other due to their shared experience in battle with life and death, they may not have agreed on everything, but their vision for China’s future was clear.

Disgraced “Lin Biao” was also a survivor of the long March and was for a long time, part of this unending loyalty bond between brothers, however, when Mao Zedong appointed Lin Biao as Defence Minister in 1959, Lin’s sights on power grew and later became evident to Mao during the Cultural Revolution that Lin Biao was very ambitious and a danger to his rule. Lin broke his loyalty to Mao and thus broke a sacred bond to a brother in arms and the revolution.

On 22 July 1977, Deng was restored to the posts of Vice-Chairman of the Central Committee, Vice-Chairman of the Military Commission and Chief of the General Staff of the People’s Liberation Army.

Deng discredited and condemned the Cultural Revolution, and in 1977 launched the “Beijing Spring”, which allowed open criticism of the violent excesses and suffering that had occurred during that period. Meanwhile, he was the force behind the abolition of the class background system. Under new direction, the CPC removed employment barriers to those deemed to be associated with the former landlord class. Its removal allowed a faction favoring the restoration of the private market to enter the Communist Party.

By carefully mobilizing his supporters within the party, Deng outmaneuvered Hua Guofeng, who had pardoned him, then ousted Hua from his top leadership positions by 1980. In contrast to previous leadership changes, Deng allowed Hua to retain membership in the Central Committee and quietly retire, helping to set the precedent that losing a high-level leadership struggle would not result in physical harm.

Deng led China through a series of far-reaching “market-economy reforms”, which earned him the reputation as the “Architect of Modern China”.

The term, “Market-Economy Reforms”, known in the West as the Opening of China, refers to the program of economic reforms called “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics” and “Socialist Market Economy”[50] in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The reforms were started by Deng Xiaoping and reformists within the Communist Party of China on December 18, 1978.

In early 1979, Deng made an official visit to the United States [51], meeting President Jimmy Carter in Washington as well as Zbigniew Brzezinski [52]. The next day, after his meeting with Brzezinski, Deng went on a tour of corporate facilities including the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Coca-Cola and Boeing in Atlanta and Seattle, respectively. The corporate visits made it clear that the new Chinese priorities were moving towards economic and technological development.

Sino-Japanese relations also improved significantly. Deng used Japan as an example of a rapidly progressing power that set a good example for China economically.

Deng quoted an old proverb, “it doesn’t matter whether a cat is black or white, if it catches mice it is a good cat.” His point was in reference to east / west politics and economics and well understood by those in the west that were about to go into business with China in the near future.

Deng’s economic reforms accelerated the market model in 1979, while the leaders maintained old Communist-style rhetoric. The commune system was gradually dismantled and the peasants began to have more freedom to manage the land they cultivated while selling their excess products on the market. At the same time, China’s economy opened up to foreign trade, mostly by high level political connections through Zbigniew Brzezinski and the Trilateral commission. Business between China and the West, was once again, back on line.

Conclusion: (Part 1)

In the years since (1912 to 1979) the fall of the Qing Dynasty and Confucian China [53], infighting by Chinese wealthy families, warlords and political idealists demonstrated a fierce determination to win at any cost while forcing their plans on the Chinese nation. In the case of Communism, Mao was very much like an Emperor of the old world and wielded power much the same way. The National Socialists that prevailed after Mao’s death, can also boast of benefitting from singular rule as demonstrated by Deng Xiaoping and his National Socialist construct. Even though Deng is considered a reformer, his constructs of power are based in a totalitarian mindset.

China moved from totalitarian rule by an Emperor, to the totalitarian rule by a communist leader, to the totalitarian governance by the leader of a national socialist state. “National Socialism” is what emerged in China after Mao’s death. Communism perished with Mao and the Cultural Revolution.

The difference between China post-communist state and those two disgraced regimes of the 20th century that embraced National Socialism is that China, has not invaded anyone…yet.

China’s partnership with western economic interests goes deeper than one might think, but China also has a long memory as the most gifted of their leaders are masters of strategic planning and have great patience when waiting for the right moment to launch their final thrust in achieving their goals.

—————————————————————————————————

Be sure to subscribe or follow Alternative Views for the continuation of China’s Rise (Part 2) where I will show how China rose from economic disaster to the most stable economic nation on Earth as well as its partnership with the western economic cartel and what the future holds for the world.

—————————————————————————————————

LINKS:

[02] Royal Chinese Imperial Dynasties

[03] Xinhai Revolution

[04] Mao Zedong

[05] The First Sino Japanese War

[06] The Boxer Rebellion

[07] The Republic of China (1912 to 1949)

[08] Empress Dowager Cixi

[09] Sun Yat-sen

[10] Kang Youwei

[11] Boxer Protocol

[12] Wuchang Uprising

[13] Last Chinese Emperor – Puyi

[14] Yuan Shikai

[15] Beiyang Army

[16] Kuomintang

[17] Warlord Era

[18] Chiang Kai-shek

[19] Chinese Civil War

[20] Communist Party of China

[21] People’s Republic of China

[22] Tokyo Trials

[23] Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference

[24] National People’s Congress

[25] The Cultural Revolution

[26] The Great Leap Forward

[27] Anti-Rightist Campaign

[28] The Great Chinese Famine

[29] Lushan Conference

[30] Liu Shaoqi

[31] Deng Xiaoping

[32] Peng Dehuai

[33] Lin Biao

[34] Maoism

[35] Jiang Qing

[36a] Red Guards

[36b] Chairman Mao & the Gang of Four, the Cultural Revolution

[37] Zhou Enlai

[38a] Henri Kissinger visits China in secret

[38b] Henri Kissinger visits China (Video)

[39] Henri Kissinger

[40] China becomes a permanent member of the UN Security Council

[41] Nixon Goes to China

[42] Deng Xiaoping

[43] The Gang of Four

[44] Trilateral Commission

[45] 1973 Oct – Kissinger Meets Chinese Officials in Beijing

[46] 1976 Tiananmen Incident

[47] Qingming Festival

[48] Hua Guofeng

[49] The Long March

[50] Socialist Market Economy

[51] Deng Xiaoping Visits America 1979

[52] 2016 Zbignieu Brzezinski in Reflection to Deng Xiaoping

[53] Confucianism

RELATED LINKS:

[A] The Opium Wars

[B] 1971 – June 30, Conversation Between President Nixon and the Ambassador to the Republic of China (McConaughy) (UN Security Council Seat) Washington,

[C] Sino-Soviet split